Deep Dive: Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing (388 HK)

Hong Kong's monopoly bourse still has increasing strategic role to play

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX) is the monopoly stocks and derivatives exchange operator in Hong Kong. It’s the largest exchange operator by market cap in Asia, and the fourth largest globally. Quality-focused investors would know that exchanges are outstanding businesses that have mostly delivered strong long-term returns for shareholders over time (HKEX has compounded at ~22% CAGR since 2000).

HKEX can be regarded as a single holding that can provide a broad, top-of-the-funnel China exposure (and a modest dividend yield) - this includes a growing coverage of China’s new economy/tech companies and increasingly the A-shares market through the Stock Connect.

Historically, the prosperity of HKEX was assured by Hong Kong’s undisputed positioning and reputation as one of the world’s premier financial hubs. However, with the city’s crumbling reputation in recent years and narratives focused on its decline, compromised status, and geopolitical risks - one may reasonably ask what is the future for HKEX. We thought this is a good time to dig deeper. It turns out, interesting and unique insights can be derived by looking at the city’s most vital financial infrastructure.

Since 2017, HKEX’s net profit and share price is up more than 100% and 80% respectively despite the progress of the ‘new cold era’ between US and China. And despite the geopolitical decoupling narrative that’s gotten popular, that is not what we see from the vantage of the exchange business. There is tendency to sensationalize the challenges and risks facing Hong Kong, while brushing aside the strategic role Hong Kong continues to play and its resiliency. Our key message here is that it is difficult to derail the Hong Kong story – much more so than most observers would think.

The objective of this report is to try to cut through the noise to separate narratives from reality, and to provide an objective picture on the opportunities and risks surrounding the business of HKEX, as well as on Hong Kong more broadly. Quality-focused investors, and anyone with a general interest in Hong Kong’s state of affairs will likely find value here.

Table of Contents

Intro: Hong Kong’s history, role, and significance

Background of the city’s development and the Hong Kong dollar

Hong Kong’s unique positioning today

Examining narratives versus reality

Decoupling narrative and capital flows

Hong Kong’s relevancy as the China gateway

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX)

Business overview

Management

Key growth drivers

Listings – current environment and opportunities

Connect Schemes – a deeper look at MSCI index inclusion and other drivers

New products – A50 futures and long-term options in RMB products and on-shore commodities

The LME debacle

Investment income optionality and exposure to rising rates

Risks and valuation

HKD and rates risk

Broader geopolitical risks

Peer valuation and justifying HKEX’s premium

Return expectations and bottom line

Intro: Hong Kong’s history, role, and significance.

From the time Hong Kong was ceded to British rule in 1842, it has enjoyed a unique role as the gateway between the East and the West. However, it was really starting in the late 1970’s, with Deng Xiaoping’s landmark economic reforms, that marked the start of a much more significant era for Hong Kong through deeper economic ties with the People’s Republic of China (“China” or “PRC” from herein).

On the back of physical goods trade leveraging China’s low cost labor and Hong Kong’s capital and ports infrastructure, flow of goods between the border skyrocketed in the 1980’s. China became the world’s factory, and with that Hong Kong also became the world’s busiest container port (at its peak in the early 1990’s Hong Kong’s GDP reached a quarter of China’s). But eventually, Hong Kong’s dominance in goods trade began to diminish as China constructed its own port infrastructure to trade directly with the world. This trend accelerated following China’s ascension into the WTO in 2001.

Adapting to this, Hong Kong embarked on a rapid transition into a services-oriented economy, turning itself into the leading provider of offshore financial services to the growing China. Ever since China’s economic opening in the late 1970’s, Hong Kong has played an important role every step of the way. It had to be nimble, adapting to changing circumstances. But historically one thing remained constant - as China gradually opened up to the world, Hong Kong stood to be a key beneficiary.

With Deng Xiaoping’s economic reform in 1978, the Hong Kong economy experienced an unprecedented boom. This set off a period of soaring inflation in the 80’s which led to rapidly weakening HK dollar. On top of this, the meeting between Deng Xiaoping and Margaret Thatcher in 1982 to discuss the eventual handover of Hong Kong resulted in ballooning pessimism for Hong Kong’s future (the “1997 problem”).

Hong Kong’s stock market, real estate, and currency all tumbled, triggering a vicious capital flights cycle. The HK dollar went on a free fall, declining almost 50% against the US dollar in just one year. In 1983, to save the freefalling currency, HKD was pegged to USD at a rate of $7.8 HKD per USD. Today, Hong Kong employs a currency board system (known as the Linked Exchange Rate System or LERS) which manages the exchange rate in the range between $7.75 to $7.85 HKD per USD.

Under the ‘One Country Two Systems’ framework, Hong Kong enjoys a distinct system from the PRC. Most notably, Hong Kong enjoys an open capital account with a freely convertible currency. Hong Kong also retained its common law legal system, which aligns it closely with other global financial centers such as London and Singapore. Through Hong Kong, international institutions are able to invest and do business with China while continuing to operate under a familiar regulatory framework as they do in their home jurisdictions. For example, as we will discuss later, this is a big reason behind the success of HKEX’s Stock Connect scheme which allows offshore investors to seamlessly own Chinese A-shares.

As a financial center, Hong Kong is the most important foreign currency raising center for PRC entities. The Connect schemes (Stock and Bonds) have also become the fastest growing access channels for foreign investors to invest in on-shore securities. Hong Kong is also the leading offshore RMB hub, with the largest pool of offshore RMB funds (~800bn or roughly half of global offshore total), and has a long-term goal to develop a deeper suite of RMB financial products and services to support a greater global role for the RMB.

For years now pundits have been calling for Hong Kong’s reduced relevance, but as we’ll argue, the reality is that Hong Kong’s strategic role continues to grow. When all is said and done, we believe Hong Kong’s value proposition remains strong despite popular calls on its demise and decline. And in turn, HKEX will continue to benefit from multiple growth channels vis-à-vis Hong Kong’s unique and strategic positioning.

Narratives versus reality

Decoupling and capital flows

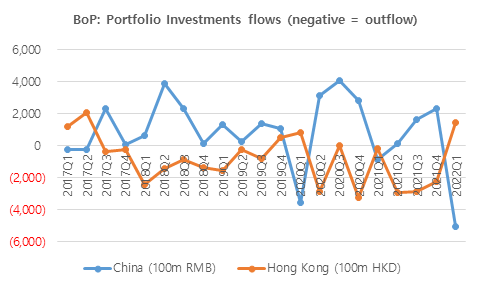

One of the common narratives is the financial decoupling between China (including Hong Kong) and the Western world. It’s often portrayed as increasing given the rise in geopolitical tensions. What do the data tell us?

Capital flows can be found as part of a country’s Balance of Payments (BoP) data. The component of the BoP that is of interest is Portfolio Investments (under Financial Account), which tracks capital inflows and outflows of listed equity and debt securities. While we see this data being quoted from time to time in various outlets, one has to be careful about making conclusions. The caveat is quite simple - capital outflows from Hong Kong has little informational value as it includes Northbound capital flowing into China. And similarly, for outflows from China, a substantial portion goes back into Hong Kong. This is trading capital that is likely to flow back into China again at some point.

This is shown above by the negative correlation between Hong Kong and China flows. A substantial portion of capital movement is simply the sloshing of money between the border. It’s not possible to conclude from gleaning outflows data that Western institutions are pulling capital out of the region. As far as HKEX is concerned, the exchange business simply earns fee income on turnover. It’s only when institutions permanently expatriate their capital out of the Greater China region which will lead to shrinking revenue pie for the exchange.

In order to better test this decoupling narrative, instead of looking at Portfolio Investments flows, investors should focus instead on two other datasets which are more informative and meaningful, in our view.

First, rather than Portfolio Investments which mostly tracks trading capital, foreign direct investments reflect more the view and confidence of actually doing business. Despite the decoupling narratives, as shown below FDI has been net positive, even in Q2 against the unprecedented backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s Covid lockdowns, and recessionary fears.

Second, and more importantly relevant to HKEX’s earnings, is Stock Connect volumes. The long-term trend is very clear. Northbound Stock Connect average daily turnover (ADT) has grown 12-fold in the last five years. Turnover of Stock Connect continues to be remarkably resilient in recent month-over-month data (below). Northbound ADT in Q2 was down only 4% QoQ in RMB terms (and 8% in HKD). And for the first half of the year, down just 9% from last year. Meanwhile, Bond Connect Northbound ADT is up 17% YoY.

“In relation to financial markets, am I seeing decoupling? From our unique vantage point in Hong Kong, at the confluence of East and West, the simple answer to that is no. We are very long way from decoupling in markets…the capital flows between East and West are deepening, and at a faster pace than ever before…we are not seeing a decoupling at all. The facts actually points to exactly the opposite.”

–Nicolas Aguzin, HKEX CEO

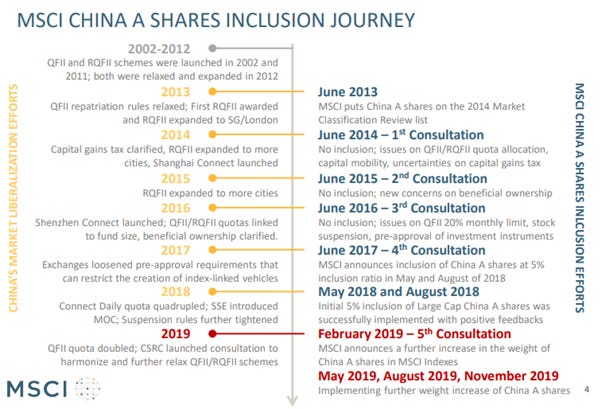

On the policy front, China has made substantial progress and reforms to improve foreign investor access over the years. Major initiatives include reforms to QFII and Connect schemes, resulting in increased investments quota (doubling QFII and quadrupling Stock Connect quotas), improving hedging accessibility for offshore investors (relaxing index futures trading rules, margin requirements, fees), embracing more free market principle (reducing trading suspensions and greater regulatory clarity), and more.

In turn, these have led to MSCI raising the index inclusion factor for A-shares in its most recent round of weight revision in 2019. This is a topic we’ll get into much deeper later, but suffice to say for now that in our view structural factors such as MSCI index inclusion is more important in dictating the long-term outcome of capital flows, rather than subjective factors like geopolitical narratives or sentiment at any point in time.

Hong Kong’s relevancy as the China gateway

China has made substantial progress in financial markets reform over the years, and its leadership has continued to indicate that the direction is towards more opening up. One of the bearish narratives on Hong Kong is that if China is to open up and establish more direct link with the rest of the world, Hong Kong would be circumvented and eventually lose its unique role and purpose. Until now, China’s opening has benefitted Hong Kong. But will this change?

“The more open China is, the more opportunities we actually have…it’s not about a binary thing where if they’re more open they are not coming here. And we are very differentiated in our roles, our functions, and our complementary strength”

– Charles Li Xiaojia, former CEO of Hong Kong Exchange

China’s approach to opening up has been incremental. “Crossing the river by feeling the stone”, as popularized by Deng Xiaoping, describes the philosophy of PRC leadership when it comes to financial reform. Every Chinese political scholar turns to the failure of the so-called “shock therapy” adopted in the reform of the USSR in the 1990’s as a precaution on why China should be extremely cautious in its own path. The sudden and complete introduction of free market principles is to be avoided. Hong Kong acts as a firewall for the financial system and provides China with greater control (albeit indirectly), reducing systemic risk as China gradually opens.

Hong Kong’s relevancy as a gateway to China is only growing. The Stock Connect is an example. Prior to this, China access was done via QFII, launched in 2002, which is a direct access program granted to select foreign institutional investors in qualifying regions. But with the phenomenal success of the Stock Connect, Hong Kong strengthened its hub status and increased its share as the Connect became the preferred channel over QFII. One of the key reasons for the popularity of Stock Connect is that by adopting global practices, it’s more friendly for foreign investors. QFII involves a more complicated approval process, costlier, and the system is harder to navigate as foreign investors have to operate within what is essentially the PRC framework. On the other hand, with Connect, investors operate within Hong Kong’s framework which is more compatible with their own.

Hong Kong also enjoys a unique relationship with PRC which cannot be replicated by other “competing” financial centers such as London or Singapore. The trust and close working relationships between Hong Kong and PRC regulators leads to enhanced and deeper scope of cooperation. Hong Kong will always be PRC’s most trusted offshore partner, and there are no substitutes for this role. From a national security point of view, you are either inside or outside the firewall. For example, consider the recent example of HKEX’s investment made in Guangzhou Futures Exchange, a newly established futures exchange in China. HKEX Invested RMB210 million for a 7% stake in GFEX and signed MOU to collaborate on climate products. HKEX is the first offshore institution that was allowed direct investment into a Mainland derivatives exchange. This kind of close collaborative relationship would not have been possible otherwise.

PRC’s stance and support for Hong Kong remains firm and unchanged - at least that’s the official communique. China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) reaffirms the adherence to One Country Two Systems, and the objective to “support Hong Kong (and Macau) in consolidating and enhancing their competitive advantages, and better integrate them into the overall development of the country”.

“We will support Hong Kong in raising its status as a center of international finance, shipping, and trade and as an international aviation hub, and strengthen its functions as a global offshore RMB business hub, international asset management center, and risk management center.” - 14th Five-Year Plan

China supports Hong Kong to continue to play an important role in its economic development and reform. The connectivity initiatives we see between Hong Kong and China is the most significant today as it has ever been.

For example, with the new Wealth Management, ETF, and Swap Connect schemes (launch in 2023), Hong Kong continues to deepen its access to the Chinese market. The RMB swap facility between PBoC and HKMA has once again been expanded recently to 800bn in July following President Xi’s visit. With this, China is guaranteeing market support to promote confidence in the development of Hong Kong's RMB market. While not yet officially confirmed, there are also reports of plans by the PRC regulators to exempt Hong Kong from the onerous cybersecurity reviews as part of corporate listing requirements. If so, this would further cement Hong Kong’s already strong status as the preferred offshore fundraising hub for PRC entities. Finally, the Greater Bay Area (GBA) is a central-level development initiative that is symbolic of the continuing important role that Hong Kong plays in the region.

We believe Hong Kong’s relevancy as gateway to China continues to grow with stronger integration. And with this, so does the opportunity set for HKEX.

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing

HKEX was formed in March of 2000 by three entities (The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Futures Exchange, and the Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company) which merged as part of Hong Kong’s comprehensive markets reform. Currently the Hong Kong Government is the largest shareholder which owns ~6% of HKEX’s shares. The government has the right to appoint six of 13 directors to the board.

The holding company owns four major pieces:

Stock Exchange of Hong Kong (SEHK)

Hong Kong Futures Exchange (HKFE)

London Metal Exchange (LME, acquired in 2012)

Five clearinghouses (HKSCC, HKCC, SEOCH, OTC Clear, and LME Clear)

Generally speaking, financial exchanges in Asia tend to take on the form of regional-based, vertically integrated monopoly operators. Regulators in Asia have historically encouraged consolidation to enhance competitiveness and improve risk management practices and visibility. Vertical integration also enables participant capital efficiency and lock-in, and is therefore an important part of the moat.

On the other hand, the exchange landscape in US/Europe tends to be more fluid and entrepreneurial. Market share tends to be a more relevant concept in the US/European markets, where regulators have demonstrated a willingness to open up the sector and allow for competition.

Open access meant that (captive business) was not possible anymore and that created competition. The London Stock Exchange, that was historically clearing 100% of its business with LCH Limited in the U.K. Just like any other exchange, it was going to give business to anyone wanting to clear it. That created competition across clearinghouses in terms of products being cleared, in terms of a collateral being called for portfolios and competition on fees. - Former COO of CDSClear at LSE (Stream Transcript)

Monopoly bourses in Asia have the characteristic of being more utility-like, enjoying more stable and predictable business (also owing to their skew towards cash equities business which is a more regional and captive business in nature). On the other hand, US/European players tends to be more dynamic, commercially focused, and competes with one another more. It’s hard to say which one is better as investors will have their own preferences.

In 2021 HKEX generated consolidated topline of HK$21bn (US$2.7bn). Topline can be broken down further in two ways, as shown in the below pie graphs.

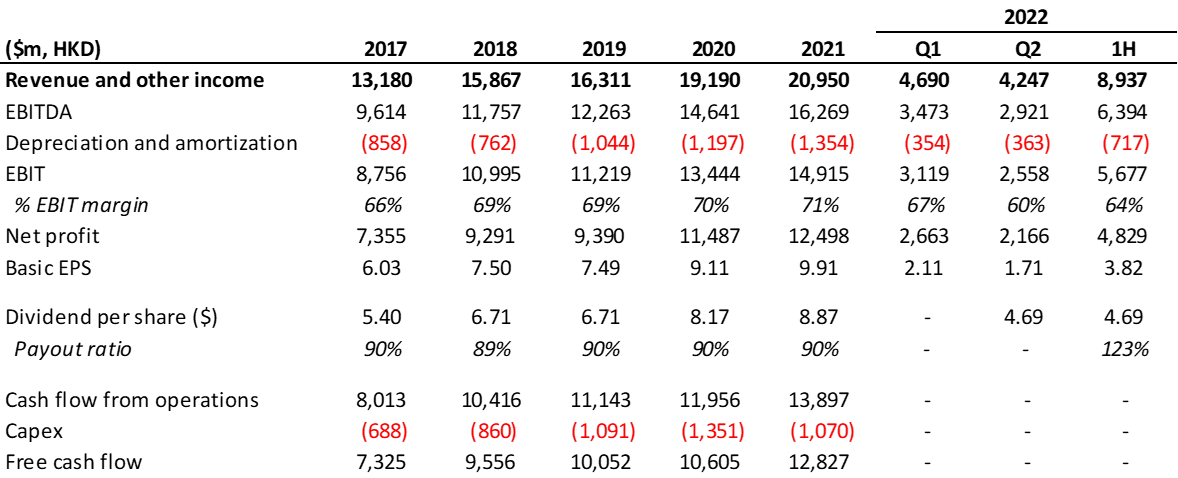

By product, HKEX is highly skewed towards equities and equity derivatives (Hang Seng index futures and options). Commodities (LME) is a relatively smaller piece of the pie. As is the case with most monopoly exchanges, economics of the business is highly lucrative. EBIT margin has expanded from mid-60% range to over 70% in 2021. 2022 has been a tough year but even in the market downturn, HKEX still managed to maintain 60% margin. Cash flows closely reflects accounting earnings, and HKEX pays 90% of its earnings out as dividend. Balance sheet is pristine. Financials are as clean as it can be.

Management

HKEX has somewhat of an interesting management structure. Nicolas Aguzin became the CEO in May 2021. Aguzin was a veteran banker who spent 30+ years at JP Morgan, most recently as the bank’s CEO of Asia-Pacific. As an Argentinian with professional background mainly in the US, he’s the first non-Chinese Chief Executive of HKEX. After the reputational challenges that Hong Kong has undergone in recent years, perhaps this choice of leadership was intentional. It demonstrates HKEX’s commercial focus and the value it places on strengthening credibility and relationship with Western/global institutions. Foreigners hold key positions in other executive roles including operations, compliance, and risk-management (COO, CCO, and CRO).

On the other hand, HKEX’s board provides the China connections. Notably, Laura Cha (Chairwoman) is also currently the Vice Chairman of International Advisory Council for mainland securities regulator CSRC (note: between 2001-2004 Laura Cha was appointed Vice Chairman of CSRC, as the first and the only person outside of mainland to join PRC central government at a Vice-ministerial rank). The board also includes members that hold directorships at mainland companies and a member of PRC political advisory body.

Under the previous CEO Charles Li Xiaojia (2010-2021), HKEX acquired LME in 2012 and had also attempted a failed takeover of LSE in 2019. It’s clear that large-scale overseas M&A has become increasingly challenging, perhaps all but impossible in this day and age when countries have become highly sensitive to protecting key assets from foreign control and influence.

It sounds like the current management has no intention on trying this again:

“I wouldn’t be tremendously focused on large international acquisitions. We think we have everything right now to succeed…there are some niche where we may use a potential acquisition/partnership/collaboration but I wouldn’t think about a big transaction that is going to make a difference right now…right now we have enough on our plate and the priority isn’t to look for a big acquisition” – Nicolas Aguzin

The departure from the company’s acquisitive past seems like a positive. Investors have less to worry about the risk of overpaying for overseas assets that have debatable synergy potential, as well as consuming management time and resources on deal-making that have lesser chance of going through. There are large enough organic growth opportunities ahead for HKEX, which we discuss next.

Listings

Historically, the US has been the preferred venue for offshore Chinese tech listings. From a regulatory standpoint, with its disclosure based system (as opposed to Hong Kong’s permission based) the US offered a less restrictive path for Chinese companies to list. The US market was also attractive with its deep pool of capital, strong investor familiarity for tech business models and an appetite for risk-taking, all leading to high valuations for issuers.

However, the ongoing threat of delisting has resulted in much uncertainty for issuers and investors. To mitigate this risk, Chinese companies listed in the US have started to pursue dual listings with Hong Kong. And to facilitate this, HKEX instituted a listings reform in 2018 which paved ways for the “homecoming” of Chinese companies. This included Chapter 8A, which allowed the listings of companies with weighted voting rights (WVR) structures. Chapter 19C allowed for a simplified listing procedure with less disclosure requirement (“secondary listings”) for companies that are already listed on another exchange, such as the one in the US. This has attracted a new wave of listings in Hong Kong (shown below).

For dual-listed shares, investors have been converting their US ADS into Hong Kong shares (the two are fully fungible and the conversion process is relatively straightforward) to mitigate US delisting risk. When Alibaba listed in Hong Kong in November 2019, Hong Kong accounted for only 2.7% of all shares issued, but by June 2022, this has increased to 36.8% (see below). JD.com has gone from 5.1% to 50.8%. US still dominates trading volume, but Hong Kong has been steadily catching up. NetEase and JD both have over 30%+ of trading volume in Hong Kong, and this is going up every quarter. At this rate we could see Hong Kong rival US market in trading volume in a few years. Given investor desire to own shares in a more stable listing jurisdiction, the trend of conversion will continue. This is all a tailwind for HKEX’s bottom line.

While not officially announced, there are also reports that Chinese regulators are considering exempting Hong Kong from cybersecurity reviews which are part of the newly established offshore listings requirements. We don’t know if this is true but in any case, HKEX offers the most stable listings environment for PRC companies. Once the current froth in the IPO market resolves, HKEX will be in a position capture the lion’s share of Chinese mega-listings going forward. As of Q2, the IPO pipeline is “very strong” according to management, with 189 active applications. Some of the largest expected or rumored listings includes Bytedance, Ant Financial, China Tourism Group, Didi, Zhuhai Wanda, Xiaohongshu, and more.

Another important point to keep in mind is that many of HKEX’s high profile listings until now have been Chinese consumer internet companies, such as Alibaba, JD, Kuaishou, and Baidu. However, in its path to become a superpower and industrial powerhouse, the depth of China’s domestic industry will continue to grow. In recent years, China continues to move up the value chain, producing global leaders in fields like renewables and EV. And as these successful companies seek to expand internationally, they may increasingly tap into Hong Kong for raising foreign currency and to attract an international investor base.

Connect Schemes

“Chinese capital markets are probably going to have the best years in the next ten years. I expect the capital markets to grow from 30 trillion dollars if we look at the Chinese capital markets, to over 100 trillion USD. In that context what we need to do is we need to continue to leverage our position as a very unique connector between China and the world”. – Nicolas Aguzin

As shown above, Stock Connect has grown a lot in recent years, and now accounts for 14% of HKEX’s group total revenue (up from 3% in 2017). Northbound turnover is about 3-4x the size of Southbound, and will continue to be the main driver. We’ve already discussed earlier the resiliency of Stock Connect ADT, even in the face of unprecedented challenges of the first half of this year.

For Northbound turnover, we believe the most important long-term structural driver for this will be A-shares index inclusion. As long as active fund managers remain benchmark sensitive (which they will), it removes much of the allocation discretion, as deviating significantly from index weight means taking on career risks for fund managers. Also, assets managed under passive vehicles are on the rise, increasing the role of indexes.

MSCI, as the leading global equity index provider with $16.7 trillion of AUM benchmarked to its indexes, has outsized influence in determining fund flows. MSCI included A-shares for the first time in 2018, setting a 5% inclusion factor (Note this is inclusion factor, and not weight). In 2019 the inclusion factor was increased from 5% to 20% (across the board impacting all of MSCI China, EM, ACWI, Asia ex-Japan, etc.) Recall MSCI is a market cap weighted index. Inclusion factor of 20% simply means A-shares (large and mid-caps) are represented at 20% of free float adjusted market capitalization. Theoretically if they want all of A-shares market capitalization to be represented, then inclusion factor would be 100%.

We don’t have the real-time data on the actual weights (MSCI charges for this!), but based on what MSCI has disclosed in 2019, after A-share inclusion factor was raised to 20%, A-shares accounted for 3.33% of the MSCI Emerging Markets index (China ex-A shares was 28.6%), and 0.42% of MSCI ACWI (China ex-A shares was 3.6%). In other words, the weights are still tiny. For example, if A-share inclusion factor was increased to 100% then for the EM index A-shares would account for 17% weight in the above case.

So the question is what does it take to get the inclusion factor beyond 20%? MSCI listed four criteria they would like to see further progress on:

Further availability and access to hedging and derivatives instruments for A-shares

Addressing the trading holidays misalignment between Chinese and Hong Kong stock market holidays for the Stock Connect

Short settlement cycle of A-shares, which presents operational and tracking challenges (China operates on T+0/1 and does not use DvP settlement mechanism. MSCI wants to see China move to a T+2 DvP system)

Allowing for ominubus trading mechanism for Stock Connect (ability to place single order on behalf of multiple client accounts, which is critical to facilitate best execution and lower operational risk).

Note that all of these criteria are related to investor access and market microstructure (nowhere does MSCI talk about things such as geopolitics or sentiment as a factor). There seems to be already solutions, or at least progress, being made for points #1,#2, and #4. #3 is perhaps the biggest challenge which may require operational reform from the Chinese side.

If you ever doubt that MSCI has intention to further increase the inclusion factor, know that MSCI’s largest customers (e.g. Blackrock) have substantial say in this process. We know that every single one of these Wall street titans wants to do more business with China. As long as China becomes bigger and more important part of global economy, and continues to be the hand that feeds Wall Street, inevitably the business case will overwhelm - recognize this is all part of the Wall Street business machine.

While index inclusion is a big determinant, increasingly there is actually a stronger case for investors to own more Chinese companies even without this benchmarking pressure, as they have become more globally competitive and come to dominate certain key industries. No longer is A-shares just about Moutai! For example, given China’s dominance in the renewables supply chain, it’s become increasingly hard for investors to gain high quality exposures to this space without owning any A-shares.

Chinese monetary policy is another factor influencing flows into A-shares. The discussion of China macro is beyond the scope of this report so we will leave it at this, but there are views that PBOC will be forced to keep easing to try to shore up the struggling domestic economy.

Looking at Southbound flows, they are smaller than Northbound and are more constrained by investor eligibility caps. Southbound flows cover about 78% of total market cap of listed companies in Hong Kong, so there is still scope to expand more. Companies currently listed in Hong Kong as secondary listing is ineligible for Southbound Connect, but once they complete the conversion to a primary listing they can be included. Notably, Alibaba has applied for primary listing, and others that have not yet done so including JD and Baidu are likely to follow. Demand for Southbound flows should remain high for PRC investors as it allows access to plenty of new economy businesses that are not listed onshore. The decision is in the hands of PRC authorities on how much capital outflow they are willing to permit.

The Bond Connect was started in 2017 with the Northbound, and Southbound was subsequently added in September 2021. China is expected to increasingly internationalize its bond market. The current 3-4% foreign ownership is one of the lowest in the world. The ongoing funding needs for Belt & Road Initiative is one reason. In addition, wider global adoption and usage of the RMB means the need to also develop deeper market for RMB investment products. HKEX’s Bond Connect has grown rapidly and in just five years since launch, Northbound ADT has reached over 30 billion RMB (roughly a third of Stock Connect ADT)

Newer Connect initiatives include the Wealth Management Connect, allowing all Hong Kong and Greater Bay Area residents to participate in qualified wealth management products offered in each other’s cities. More importantly perhaps is the Swap Connect which will launch in 2023, facilitating access to the IRS market and synergizing with the Bond Connect by allowing participants to better manage rates risks. As these initiatives are still very early stages, we are not going to try to speculate much on their success. Suffice to say however that HKEX’s track record has been excellent so far. And one thing is certain – Hong Kong continues to expand its breadth and depth of China market access.

Product growth

In equity derivatives, HKEX traditionally has had the lion’s share of Hang Seng derivatives products (Hang Seng/HSCEI index futures and futures options). Since October 2021, HKEX started to offer A-shares index futures based on the MSCI China A50 index. Singapore Exchange (SGX) is the leading equity derivatives exchange in Asia, and the only competitor that offers a competing product offshore (based on FTSE China A50).

HKEX’s MSCI A50 futures has quickly made share gains since launch in October, challenging SGX’s monopoly. In less than a year, it has captured more than 15% of ADV. How does MSCI A50 compare to the FTSE A50?

MSCI A50 has higher weights in new economy/tech companies over consumer staples and financials relative to FTSE A50, as shown below (Consumer staples + financials accounts for 57% of FTSE A50 vs. just 33% for MSCI A50). As it reflects a more up-to-date representation of the dominant investment theme in the A-shares markets, MSCI A50 has the benefit of higher investor interest (and as a result, FTSE/SGX has been contemplating making major changes to its index).

MSCI basically prided itself on having a single scheme of having a fairly rigorous and comprehensive approach to their indexes worldwide…I think, MSCI is continuously regarded as probably the highest quality provider overall...FTSE Russell was known in the industry to a fault, I would argue, for being more flexible and more willing to work with individual customers to design indexes that very specifically met their needs even if they didn't fit particularly into the more holistic view of the world

- Managing Director, Information Services at LSE (Stream Transcript)

Another point is that HKEX offers a one-stop shop in A-shares combining cash equities and index futures (while SGX lacks the former). For example, it makes less sense for investors to be buying A-Shares through the Connect while hedging on SGX, when HKEX can now provide the same.

While A-share index futures is the most important near-to-mid term product driver, there are two long-term growth optionalities.

The first is RMB products. Notably, dim sum bonds sales have surged recently (although it remains to be seen whether this trend is durable). According to FT and Refinitiv, volume of dim sum bond offerings have risen 145% from a year ago to RMB 126.8bn. One catalyst has been the cheaper relative cost of RMB funding due to US rate hikes, prompting more issuers to raise funds in RMB. The addition of Southbound Connect has also led to increased demand to absorb issuances as mainland institutions hunt for higher yields offshore (below chart). If RMB’s share of global usage grows, there could be more natural demand for RMB bonds, however this is still premature to say.

The second long-term optionality lies in bridging access to China’s on-shore commodities markets. Over the long-term, China wants to gain market share of global price discovery for the key commodities it imports, rather than relying on foreign pricing centers including the CBOT. Longer term China is likely to try to shift the center of gravity towards its own side.

To become a credible global pricing center however requires a compromise - China must increasingly open up its market to foreign participants. Just recently we have seen Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE) and Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange (ZCE) open their soybean and rapeseed oil markets to foreigners. However, there is likely to be friction in this as foreigners may still find accessing and working the Chinese system a challenge. And this means there will be opportunity for HKEX to act as a facilitator, just like how it did in stocks and bonds. We don’t yet know what this will look like, but perhaps could take shape as another “Connect”. HKEX’s recent investment in the Guangzhou Futures Exchange is supportive of their interest in the on-shore commodities market.

The LME debacle

LME has undergone significant controversy this year from the famous nickel trading incident back in March. We won’t be retelling the entire story here as press coverage has been extensive, but instead touch on some of the significance and implications.

The big deal here wasn’t that trading had been suspended (this is not uncommon). It’s the retroactive cancellation of trades that had already gone through (~8 hours prior to the suspension) that raised eyebrows. Roughly US$3.9bn in transactions were cancelled, and an estimated $1.3bn of paper profit had been reversed as a result. The losers from this were the hedge funds whose winning positions were cancelled (it is said that about half of the winning positions accrued to Paul Singer’s Elliott Management). The obvious winners here were the Chinese tycoon Xiang Guangda and his firm Tsingshan, as well as his creditor banks.

While the media was quick to speculate potential Chinese influence through HKEX ownership, this is simply unknowable. It’s just as plausible that LME’s management simply tried to save itself. Had margin calls been defaulted on, LME Clear’s default funds of mere $1bn may not have been sufficient. Failure of clearinghouse would attract unprecedented regulatory attention (in addition to virtual guarantee of management getting sacked). It’s kind of telling that immediately following the event, LME doubled its clearinghouse default fund to $2bn (among other new measures including daily price movements of +/- 15% and additional disclosure requirements focused on participants’ OTC positions).

Obviously, people are saying the LME lost its credibility after that but I think they were just doing what they had to do to protect any further fallout. I think J.P. Morgan were also in bed with Tsingshan in terms of finance and so they had a lot to learn too. It's just something that probably we'll never know the true ins and outs of.

- Global Head of Nickel Derivatives Book, Transfigura (Stream Transcript)

As for the implications on HKEX, there are two: lawsuit and reputational damage. Elliott has sued LME for US$456m. In case this is awarded, HKEX may have to step into bail out LME. The amount would not be large enough to really move the needle for HKEX, however. LME’s reputation has certainly taken a big hit as some participants have reportedly ceased doing business with it. But given LME’s global dominance, it remains to be seen how impactful this could be. For HKEX, this ordeal has also brought about a compromised image and negative press coverage. Whether the Chinese interference is true or not, the chance that HKEX is allowed to purchase any overseas asset has probably gotten even slimmer after this incident.

Interest income

Exchanges have the ability to earn interest income on funds posted by participants (margin and clearinghouse funds). When interest rates globally were higher in the past, this source of income used to be quite meaningful for many financial exchanges. In recent periods of low interest rates, this has all but disappeared, but as rates rise again we are seeing this becoming meaningful again.

HKEX defines its “investment portfolio” as the sum of participants’ funds and its own corporate funds. In Q2 2022, total fund size averaged HK$325bn, with $291bn being participants’ funds and $34bn corporate funds. Participants’ funds are invested entirely in cash or near-cash items including deposits, government bills, and investment grade debt. It earns a low yield on a large asset base. Corporate funds have a higher risk component to the allocation including equities and mortgage backed securities (which are managed by external managers)

The returns generated using corporate funds is not “pure” profit, since there is associated cost of capital - corporate funds belong to shareholders and there is opportunity cost to this. However, profit generated from participants’ funds can be considered true profit as the cost of capital is negligible for HKEX’s shareholder (i.e. it is borne by the exchange participants who forego their share of returns). Investment income is reported net of disbursements to participants.

Due to Hong Kong’s monetary system (LERS), it ends up having to “import” US dollar interest rate. As shown below, as of the date of this writing (September 6) 1-month HKD Hibor has tracked USD Libor and is approaching almost 2% (but still 75 basis points below USD Libor).

Below is a simulation of the participants’ fund income based on above interest rate trajectory (Q1 and Q2 are actual reported numbers):

In Q2, when the average Hibor during the quarter was 0.30%, participants’ funds generated income of HK$304mn (0.43% annualized on $291bn). Participants’ fund returns is higher than 1-month Hibor as maturity profile of deposits is longer (average maturity of roughly seven months). Participants’ fund income accounted for 12% of Q2 EBIT.

In Q3, Hibor has risen substantially. Based on the average Hibor QTD (1.36%), we estimate HKEX will generate ~HK$1.2b of quarterly income from participants’ funds, which is 46% of Q2 EBIT.

Additional scenarios corresponds to assuming quarterly run rate at current Hibor rate of 1.93% (Run rate 1 scenario), and assuming Hibor rate converges to current USD Libor at 2.68% (Run rate 2). In these cases participants’ funds income could grow to 66-91% of Q2 EBIT.

HKEX is hedged against rising rates. With 90% dividend payout ratio, a substantial portion of this investment income could be returned to shareholders. This is an optionality that investors should take into account.

Although the exposure to rising rates may seem lucrative, we do however need to caution that rising rates can add systemic risks to the picture. While the Hong Kong economy may stomach a 200 basis point rate increase without blowing up, the risks do get bigger if rates were to go up substantially from here. Being unable to set its own interest rates, Hong Kong must continue to import the Fed’s rate hikes.

Risks

The bear thesis on the HKD has been widely discussed by short-sellers, most notably Kyle Bass. We’re not going to reinvent the wheel on this discussion, but the basic conundrum of their argument is that Hong Kong has to choose between savings its currency or the economy. Assuming USD rates continue to rise, protecting the HKD currency peg requires importing higher interest rates, which will eventually put significant strain on Hong Kong’s economy.

During the Asian Financial Crisis, the currency peg was successful defended but between 1997 to 2003 Hong Kong’s real estate index dropped 70%. Bears argue that Hong Kong won’t survive another major deflationary bust this time around due to the significantly higher leverage in the system, which could trigger a banking crisis and a vicious cycle of outflows (eventually breaking the peg).

On the other hand, HKMA has a very successful long term track record in protecting the peg, having done so successfully for the last 40 years and managing through many crisis including AFC, GFC, and the 2019 Hong Kong protests. More important is the fact that in 2019, PBoC and HKMA signed a one-way USD swap agreement during the height of the Hong Kong protests when the exchange rate was testing the upper bound of 7.85. This is an endorsement that China will be backstopping the HKD. The reality is that HKD can only be broken in the event that both Hong Kong and Chinese authorities fail to respond. Shortsellers have some work cut out in front of them, it seems.

There are debates as to China’s adherence of One Country Two Systems and how this could change going forward. There’s the “2047 problem” when the city’s current arrangement expires, although it is far away enough that it’s probably not a pressing concern for investors at the present. We simply don’t think there is much upside for the PRC to turn Hong Kong into another mainland city like Shanghai or Shenzhen, but this is anyone’s guess.

Zooming out and examining the geopolitical risks, one thing to make clear here is that geopolitical risks can actually work to the benefit of HKEX. As we’ve seen, the hostility in the US listing environment is providing HKEX with more opportunity to take market share. In an environment where there is some degree of geopolitical fear, HKEX can thrive. And clearly this has been the case until now. So when referring to risk in a real existential sense, we need to be more specific – it’s really the extreme tail risk where geopolitical conflict escalates to the point of permanent decoupling and no return – the “Russia” scenario – that investors need to be concerned about.

A war over Taiwan strait could be one such scenario. But besides a kinetic conflict, there are other theoretical “soft nuclear” outcomes, for instance Washington can suspend free trading of USD with HKD, try to remove Hong Kong from the SWIFT system, or ban US entities from owning Chinese stocks. We believe these are extreme and unlikely scenarios. If they were to happen, it would likely set off a course towards unprecedented escalation and a chain of devastating tit-for-tat outcomes for both sides.

With all this being said, we recognize and respect the fact that a wide range of views exist on China and geopolitical risk. Investors in Western markets will have to work out how much they are comfortable with owning Chinese equities. Our philosophy at Value Punks is that geographical diversification is a sensible one, as we have discussed in our past memo here. In any case, many of Value Punks subscribers are already global allocators/managers that maintain a balanced global exposure and a non-zero allocation to Chinese equities. In such a case, we think HKEX continues to be a high quality, top-of-the-funnel way to gain China exposure which should be on every global investor’s watch list.

Valuation

HKEX has market cap of HK$382bn (at share price of $302). To derive the enterprise value, we need to subtract corporate funds of $34bn (includes cash and cash equivalents of 13bn and 18bn of equities and other securities). Then add back 500mn of cash that cannot be used freely (skin-in-the-game and default fund credits to support clearinghouse) and debt of 426mn.

At an EV of $349bn, HKEX trades at 28x FY21 net profit, or 36x if we use 1H22 annualized net profit. HKEX is trading at about the average of its own PE of the last ten years, as shown below.

Among listed financial exchanges globally, HKEX has always traded at a premium to peers, due to higher quality and growth expectations. This seems warranted. As shown below, relative to peers, HKEX has lower debt, higher trailing 5-year revenue growth rates (note: LSE growth rate is skewed by its Refinitiv acquisition), higher return on capital, and higher margins.

With current dividend yield at 3.1%, investors could get to double digit returns if they are willing to underwrite 7-8% annual earnings growth (assuming multiple stays constant). 7-8% growth looks fairly reasonable in relation to the structural growth drivers discussed in this report, and also relative to historical track record (2017-2021 when earnings compounded at 14%).

Multiples are high but will likely remain so supported by the long growth runway. However, the risk here is twofold. Should expectations of growth slow down, multiples could fall in line with global peer average levels of 20-25x. Also, concerns over macro and geopolitics could result in multiples contraction - for example as we have seen in 2018 (p/e from peak of 43x in January down to 25x in October) and in early 2022 (40x in January down to 30x in March).

At the current multiple, we believe HKEX is trading at roughly fair value. Historically shares have found strong support at 25x p/e which corresponds to a share price of ~$250. Our current position on the shares is disclosed below.

Disclosure: the author does not own a position in the securities mentioned in this report

If you are looking for an expert network to get up to speed on industries and companies, then we highly recommend Stream by Alphasense.

Stream by Alphasense is an expert interview transcript library that has been integral to our research process. They are a fast growing expert network with over 15,000 transcripts on a wide variety of industries (TMT, consumers, industrials, real estate and more). We recommend Stream for its high quality transcript library (70% of experts are found exclusively on Stream) and easy-to-use interface. You can sign up for a free trial by clicking here.