Summary

Xiaomi has an ambitious goal to surpass Samsung to become the #1 smartphone brand in the world (shipment basis) by 2024.

We believe Xiaomi is less like the “Apple of China” and more like the “Costco of smartphones”. We explore the key aspects of this business model, including services monetization and an ecosystem strategy leveraging an “investment + incubation” model.

Most investors seems to understand Xiaomi’s market share growth story, but may yet be underappreciating its monetization potential. Bull case can be built on handset premiumization and services revenue growth outside of China. The recent global fallout of Huawei and the shift in ad spending allocation triggered by the rollout of Apple’s iOS14.5 are worth noting as business tailwinds for Xiaomi.

Smartphones are still a tough business at the end of the day, which is why having good management is crucial. Founder/CEO Lei Jun is one of China’s best tech CEOs. If you are bullish on Xiaomi, Lei Jun must be a big reason why.

Our price target for FY24 is HK$24-33, for 3-year CAGR of between 13-26%.

Context

Mainstream media has often referred to Xiaomi as the “Apple of China”. If you take away only one thing from this report, it is to please please rid of this lazy analogy. The two companies have different strategies and serve totally different end-markets with almost no overlap. We take issue with this as it gives a misleading impression that Xiaomi is some kind of a copycat company. This is not only not true, it is harmful in obtaining a proper understanding of the business. Here, at Value Punks, we will try to give Xiaomi the treatment it deserves. Let’s build some context first!

Xiaomi was founded in 2010 by Lei Jun and a seasoned team of seven other co-founders (out of the eight, five are still with the company today including Lei Jun). The opportunity they saw at the time was simple. Apple was selling the best phones in the world, but at a price that was not affordable by the vast majority of the Chinese population. Emerging markets needed emerging market prices! For smartphones, the Chinese market was split in two extremes - you had either high-end phones that were prohibitively expensive, or you had cheap phones that were hardly usable. The “affordable and good enough” category was waiting to be captured (Clayton Christenson would be proud!).

From the beginning, Xiaomi cultivated an image of being an honest brand, favored by the young, hip, and the geeky who were all drawn to the brand for its high value-for-money. Xiaomi sold its phones exclusively through its own online store, minimizing distribution cost. Despite being a low cost maker, Xiaomi successfully built a spirited brand and a vibrant community of loyal users. Its community (called “Mi-fans”) became a passionate contributor of product feedbacks and ideas. Xiaomi positioned the community at the center of its product development, which is a culture that is still at the core today.

There is an anecdote of when Manu Jain, Xiaomi’s current India region head, first joined the company and spoke to one of the co-founders (we’re guessing this is either Lei Jun or his right hand man Lin Bin). Manu recalls:

“I remember one of the meetings…he asked me this question: How much was your marketing expense in your previous company? I gave him the answer. Then he asked: “Take a guess Manu. How much do we spend in marketing?” Because he asked that, I assumed the number was fairly low, so I said something like 5-6%. Guess again. I said maybe 2-3% because I assumed at least 2-3% of the revenue would be spent on marketing. Then he stood up and went to the board – and he drew a big zero.” (Times of India)

This is a peek into Xiaomi’s culture. It’s an entrepreneurial and resourceful company that knows it needs to be efficient and smart to win. This is Xiaomi’s approach to entering all of its overseas markets. In India, Manu Jain claims that Xiaomi spent zero marketing during its first three years, and yet still beat Samsung to the #1 spot.

[Author’s note: marketing expense is not actually a “zero”. Consider Xiaomi stores (just like Apple stores) which showcases its products. It is really a marketing expense, just not classified as such. But it is true in general that Xiaomi spends much less on actual ads (digital and traditional) than its competitors. Especially compared to competing Chinese brands like Oppo/Vivo which employs aggressive spending strategy focused on celebrities/influencers and store rebates]

Xiaomi took over the Chinese smartphone market by storm with its early product successes. However, success attracted competition. Competition in the Chinese market quickly intensified. The years from 2016-2017 saw the toughest period, and Xiaomi’s sales growth came to a halt as competing brands like Vivo, Oppo, and OnePlus spent aggressively to gain share. But as Xiaomi started to feel more pressure in China, its overseas sales took off in a massive way. Xiaomi became the #1 smartphone brand in India in the third quarter of 2017, overtaking Samsung – a position which Xiaomi has held for 16 quarters since then. At the same time, Xiaomi expanded into multiple overseas markets across all continents – becoming a truly global brand.

So it’s been quite the story – in just ten years, the company went from nothing to becoming the third largest smartphone maker globally (by shipments), closely behind Apple. Behind this is Lei Jun, the company’s founder and CEO. We need to talk about this key man.

Lei Jun

Lei Jun hardly gets the spotlight from Western media, although he is considered a legend within China’s tech circle. Even worse, when Western media mentions him, he has often been portrayed as sort of a “Fake Steve Jobs”. Again, this is harmful and English language coverage doesn’t do him justice at all (especially since Lei Jun doesn’t speak English well and has only given interviews in Chinese).

In the Chinese tech circle, Lei Jun is actually more often compared to Elon Musk, rather than Steve Jobs. Both Lei Jun and Musk are technical founders (engineers). Both have had a history of business successes already before founding their respective companies – Musk in Paypal and Lei Jun with Kingsoft and through subsequent experience as an angel investor. Like Musk, Lei Jun also has a sizable personal fan base (you could call it a cult). However, Lei Jun’s personality and image is quite the opposite of Musk – not flamboyant and polarizing at all. Lei Jun is known for being soft spoken, humble, down to earth, yet infinitely ambitious.

After graduating Wuhan University with a degree in software engineering, Lei Jun joined Kingsoft (software company) in 1992 as the company’s sixth employee. He worked his way up to becoming the CEO in 1998. After resigning as CEO of Kingsoft in 2007, he became an angel investor, investing in several notable companies including Vancl.com (online apparel), UCWeb (mobile company acquired by Alibaba), and YY (livestreaming), and had quite a successful investing career. Some may not realize this, but Lei Jun has always been a pure internet and software guy - he said himself that he hasn’t even touched hardware business until he started Xiaomi. Xiaomi calls itself an “internet company”, and while you may say this is just PR talk, there is actual truth to this. Lei Jun has always described his own management philosophy as being founded on an “internet and software way of doing things”.

Then, at the age of 40 Lei Jun became an entrepreneur and started Xiaomi. He was famous for saying:

“Liu Chuanzhi (founder of Lenovo) became an entrepreneur at 40, Ren Zhengfei (founder of Huawei) at 43, I don’t think much of myself starting a brand new journey at 40”

Indeed, the entrepreneurs that are the most relentless are ones like this. Lei Jun had made a lot of money from his successes early on, and could have just led a cushy life as a wealthy angel investor his whole life. Yet, he’s chosen a life of grinding himself down in one of the most competitive businesses in the world. He’s doing this to win, and this is one of the reasons why many investors and Mi-fans have a tremendous amount of respect for Lei Jun. Also, not many CEOs have his skill mix which consists of technical/engineering background combined with his understanding of the financial/business side from his investing career.

For anyone who is bullish on Xiaomi, Lei Jun must be a big reason why. At the end of the day, smartphones are a super competitive business, especially so for a young firm which is going up against the giants of the industry. There is no comparing Xiaomi to Apple – the latter can afford to run on autopilot for some time, while the former can’t. Therefore, it’s all the more important that investors select the right jockey. Lei Jun owns 55% of voting rights so investors are stuck with him. But in this case, it’s a blessing.

Business model

Now let’s dive into the Xiaomi business model. We believe there are three aspects which makes it unique, which are discussed below.

The “Costco of smartphones”

We’ve shunned the use of “Apple of China”, but in terms of an analogy for Xiaomi, we find that the “Costco of smartphones” is more appropriate.

Just like how Costco deliberately keeps its profit margin low in order to share value with its customers, Xiaomi has also adopted a policy to keep its hardware net margin below 5%. If it reaches that point, then Xiaomi will return all excess profit to customers. For all Nick Sleep fans, yes, we can also call this ‘scaled economics shared’. In fact, Lei Jun stated in an interview that his trip to a Costco store in the US inspired him to adopt this (as an aside, Lei Jun might not speak good English but he is a very keen observer of successful businesses in the US).

When it comes to monetization, Costco makes 60-65% of its profit from membership fees. For Costco, membership fees accounts for just 2% of its net sales, but comes at ~100% margin. Similarly, Xiaomi sells hardware at thin margins, but monetizes the business primarily through the “Internet Services” segment, which is a combination of ads, revenue share of in-app purchases, and subscriptions. More on this later.

From time to time we’ve seen investor criticisms regarding Xiaomi’s low margins. But just like how you wouldn’t say that Costco is a bad business given its low margin, we think this criticism is off the mark. This is what happens when you only view the company through the lens of “Apple of China”.

IoT strategy

Xiaomi calls itself “the largest IoT brand in the world”. It uses its presence and brand in smartphones as an entry point into selling various household and consumer electronics products. It has a huge product portfolio – see below. TVs and laptops accounts for 30% of sales excluding smartphones. Smart home and appliances is also a big category.

Xiaomi has the top market share in several of these in China – #1 in smart TVs, #2 in wearable bands, #2 in robot vacuum cleaner, #1 in air purifier, #1 in smart door locks. Clearly, Xiaomi has succeeded in developing “killer” products. In some of these products, there was a lack of a recognized brand or category leader until Xiaomi entered. Case in point: smartphone power banks. Even though it was a crowded space, Xiaomi entered and won with its branded, high value-for-money product and took share from a long list of less known makers.

The Costco analogy applies here again. The size of Xiaomi’s product portfolio might be surprising to some investors, who might say the company seem unfocused with its approach. But the value proposition here is that Xiaomi is aiming for a consistency in the high value-for-money it offers across its entire portfolio. If you think about Costco, it too sells a whole bunch of stuff. If I told you that there’s a store selling jewelry next to baked goods, you’d probably be highly skeptical. But at Costco, shoppers don’t care. They are willing to put anything into their shopping cart, knowing shopping at Costco is satisfaction guaranteed. Xiaomi is looking to recreate exactly this – a consistently reliable value-for-money brand for consumers. A former employee at one of Xiaomi’s competitors (OPPO) has mentioned:

“That brand confidence or that promise that they delivered helps in the customer being able to buy a Xiaomi product knowing that it will be a value-for-money product…you know that you’re getting their basic acceptable quality. You’re assured of that, you don’t feel nervous about it, and at a price that very few can match”

– former Head, Retail Image at OPPO (Source: Stream by Alphasense, 6/2/2021)

The grand vision Xiaomi has is that most of these IoT products can be linked to the smartphone and can be controlled through a single “Mi Home” app. Their “IoT vision” is still in early stages, but the company has been making progress. Users with at least 5+ Xiaomi devices connected was 8 million in the third quarter, up 43% yoy. Meanwhile the MAU of Mi Home app has reached 60 million, up 39% yoy. We can see that Xiaomi has been able to cultivate a growing base of highly loyal users. And this is important, because when consumers use multiple Xiaomi products, they are more likely to come back (same thing with Apple). So far, they have clearly succeeded in developing killer products – the next stage for management is to continue to execute on the connectivity between the products, creating a true ecosystem.

Investment + incubation model

Given the size of Xiaomi’s product ecosystem, one might ask – how does one company do all of these? Well, turns out there’s actually a method to the madness! Xiaomi found a way to broaden its storefront without bloating the organization, and that’s through its investment + incubation model. Xiaomi takes minority stakes in hardware startups, and turns them into ecosystem partners (so far it has invested into 120 ecosystem partners). Xiaomi’s management prefers this model over conducting outright M&A. It allows them to enjoy synergy with its investees, but doesn’t take away much management resources and doesn’t require integration.

One of the benefits to this model is that it gives Xiaomi access to the best teams in the industry. What do we mean? Some of the most talented founders and engineers in the hardware industry works in small groups. They prefer the nimbleness of a small operation rather than being part of a big company. As an example, consider Huami which makes wearable for Xiaomi. Huami is known for having a top notch hardware engineering team, possessing proprietary knowhow for long battery life technology in wearables. The core team at Huami have worked together for 20 years, and if Xiaomi had tried to acquire this company outright or poach individual members of its team, it would not likely have succeeded. But through the investment model, Xiaomi was able to tap into the talents at Huami immediately.

There is a win-win relationship between Xiaomi and its ecosystem partners. Xiaomi benefits from being able to broaden its storefront and increase the number of touchpoints with its customers. For Xiaomi’s partners, they can use Xiaomi distribution channel (both offline and online) to sell their products. Not only in China, but Xiaomi could help these companies sell in overseas markets. In addition, partners value the supply chain management support that Xiaomi offers, as most startups have no experience in scaling production.

However, there is also a tricky dynamic for Xiaomi to manage with its partners. Partners are wary of overreliance on Xiaomi. Some of them want to eventually develop and grow their own brands. For example, Huami wants to make its own branded fitness bands. So this is a balancing act for Xiaomi. The conflict needs to be managed especially as partners grow in size and develop their own ambitions. But in the end, even if the partnerships end up in divorce, Xiaomi would have already established a strong position in the relevant product categories. At the end of the day, consumers don’t make the distinction which ecosystem partner makes the product. So Xiaomi likely gets to keep its volume. In any case, Xiaomi is unlikely to lose in a game where it has created its own rule.

The smartphone business

Market share trend

“Xiaomi” (Mi series, Civi, Mix) is the company’s flagship brand, while there is also “Redmi” which is the discount lineup. We won’t go into any phone specs or model details here – we refer the reader to specialist review publications like TechRadar and others. Here, we’ll focus on the bigger picture analysis.

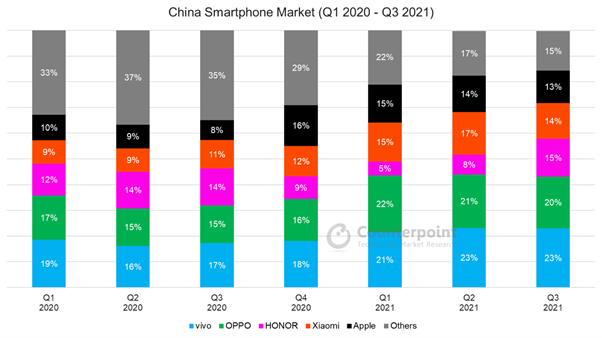

Xiaomi is the third largest maker with roughly 200 million units, closely behind Apple. In China it is the fourth largest, behind Vivo, Oppo, and Honor (spun out of Huawei after the US sanctions).

The global smartphone industry has been consolidating. Since 2019, the top five global brands (including Xiaomi) have increased their market share from 55% to 67%. Similarly, in China we have also seen the top five increase share significantly, to now 85% of the market.

In China, smartphone volume has reached saturation, with long-term demand expected to stabilize at ~300 million units annually. Xiaomi’s market share has fluctuated in the range of 10-15% through product cycles, and gaining more share on top of this won’t be easy. In China, what success looks like for Xiaomi is to defend and maintain its volume, while riding the premiumization wave (more on this later).

Sales outside of China now accounts for 52% of revenue. India, where Xiaomi has 29% market share, is the company’s most important overseas market. As we said earlier, it overtook Samsung in 3Q 2017 and impressively held the #1 spot for 16 consecutive quarters since then. We’ve come across multiple former employees of Xiaomi who spoke of almost flawless execution in the country under CEO Manu Jain, who at the age of 34 became Xiaomi’s India head and built the business there from nothing. One former employee, in response to a question about Xiaomi’s India business, said:

“We’re killing the market…It’s funny because my boss in Xiaomi, my boss is CFO, but he got switched to the international sales department. Before he was going there, he was quite concerned too but as soon as he left our team, he’s like “My KPI is so much easier to manage”. Selling phones in India, for our price, we’re not facing too much competition there.

– former Director at Xiaomi (Source: Stream by Alphasense, 1/8/2021)

India accounts for about 40-45% of Xiaomi’s sales outside of China. The rest of overseas sales consists of mainly Europe (Xiaomi market share 20%) and Latin America (market share 15%), and also Southeast Asia, Middle East, and Africa. Xiaomi is truly global.

As shown below, Xiaomi held the #1 spot in 11 countries in 3Q21 (up from 10 in 3Q20), and was top 5 in 59 countries (up from 54 in 3Q20). If you are still associating Xiaomi as just an emerging market brand, then think again –it also has high share in developed Europe including France, Spain, Italy, Greece, Germany, and Sweden. These markets are a proving ground for Xiaomi’s premiumization strategy, and sales growth in these regions have helped boost Xiaomi’s average selling price.

Management has set an ambitious goal to become the #1 global smartphone maker (shipment basis) by 2024. Xiaomi sold roughly 200m phones in 2021, versus the industry leader Samsung at 260-270m. Xiaomi is aiming for ~270m units in 2024, driven by sales outside of China, and primarily further share gains in Europe and Latin America.

Distribution

We won’t be able to get into the distribution dynamics for each market. But at a high level, the market globally can be separated into two: where telecom companies play an important role in phone distribution through bundled phone plans (North America, Europe, and South America), and where majority of customers purchase their own phones through independent online and offline channels (most EMs including China and India). For example, in India, 90% of the market is on pre-paid and not multi-year plan subscriptions. Even though the operator market is nearly a duopoly between Bharti and Jio, they don’t have as much power in influencing handset distribution.

Xiaomi’s modus operandi in most of its markets has been to start out by selling phones exclusively through its own online channel, and doing so with little to no marketing spend initially. Through this low cost approach, it is able to provide customers with value-for-money products that no one else can match. Once it gains momentum, it starts to broaden the channels by investing more into offline store networks (both own stores and partner retailers), and starts to spend more on marketing.

In China, Xiaomi has been accelerating its offline store investments. In a market where 70% of phone sales is offline, Xiaomi is the reverse where 70% of its sales is still online. Xiaomi now has 10,000 offline stores (up from 3,000 one year ago), and by continuing to expand the offline store network in lower tier cities, the company plans to grow to 30,000 stores in the next three years (most of this is partner stores). There are operational risks to a rapid store network expansion and this needs to be monitored. Xiaomi has emphasized that it’s working to execute this correctly, including ensuring fair/uniform pricing policy, unified sales & service, and constructing a win-win model with its partner retailers.

Generally speaking, Xiaomi is more conservative than its peers in its offline strategy. When it comes to offline retail, Xiaomi emphasizes efficiency. Management believes even with spending less rebates than competitors, it can achieve comparable ROI for its stores, due to faster turnaround time, and a strong IoT portfolio which helps to drive foot traffic and additional store revenue. Management claims 80% of its stores in China are generating a positive profit, and those that do are making 30%+ ROI.

Premiumization strategy

Premiumization is very important to Xiaomi’s long-term monetization success. The significance of premiumization is not just that Xiaomi can reap higher gross profit from selling phones with a higher price tag. But it’s also the key to enable higher services sales. Users of premium phones are more affluent and are worth more to advertisers. They also spend more money on in-app purchases (up to 4x more for games according Xiaomi) and use more subscriptions and other services.

Has Xiaomi been able to execute on premiumization? It’s early days still, but so far the answer is yes.

As shown above, Xiaomi has been growing its market share across all of its premium ranges (RMB3,000-4,000 / 4,000-5,000 / 5,000+). Share gain has been the greatest in the RMB3,000-4,000 and 4,000-5,000 ranges. At the 5,000+ range it’s harder because it’s dominated by the high-end flagships like iPhones and Samsung Galaxy. Most users of these phones are not looking at Xiaomi as a substitute.

Here, it is important to note the global fallout of Huawei. Huawei used to command 30-40% handset share in the Chinese market, but has fallen to about half since late-2020. Huawei also became one of the leading brands in many overseas markets, before being gored by sanctions. Xiaomi took advantage of Huawei’s downfall and made an aggressive push in the premium category, both in China and overseas. This seems to have paid dividend. Notably, the Huawei fallout has been more than just a one-off share gain for Xiaomi. This important point was explained by a former employee, who was in charge of all overseas markets for Xiaomi outside China and India:

“I don’t think we can ignore the fact that Huawei is decreasing its market share very significantly. We try not to within Xiaomi get into anything political, but for us, it was an opportunity. It was an opportunity to gain a lot of the partnerships that Huawei had lost. We’re talking about definitely outside of China and a lot of the carrier relationships, a lot of people, human capital. That was a tremendous opportunity for Xiaomi and especially in markets such as Europe and now Latin America.”

– former Director at Xiaomi Global (Source: Stream by Alphasense, 4/6/2021)

Importantly, establishing these new carrier relationships is extremely important in markets like Europe and Latin America, where carriers occupy an important role in handset distribution (by some estimates 50% of distribution is controlled by the carriers). These new carrier relationships are critical for Xiaomi to execute its premiumization strategy. You need carriers to help support and promote your new premium phones. In addition to gaining new carrier relationships, Xiaomi has been able to poach former employees of Huawei, who have the reputation for being the most competitive and ruthless bunch in the smartphone industry. With these, Xiaomi has secured a better foundation for future growth.

Xiaomi’s average selling price (wholesale) has been increasing, reaching a high of RMB1,116 in 2Q21 compared to RMB881 four years ago, for roughly 5-6% annual ASP growth. Note that this was achieved despite the rapid growth of low-priced India. This means regions outside of India experienced faster ASP growth. China has gone from RMB1,700 in 4Q20 to 2,100rmb in 2Q21. In terms of ASP, it is the highest in Europe, followed by China, then India/other EMs. In response to whether brand perception is changing for Xiaomi into a more premium brand, the same expert above responded:

“Actually, yeah. Xiaomi has been very good about making sure that all of these [campaigns] are tracked and that brand perception is surveyed on an annual or semiannual basis. I think the fact that the company is selling more high-end phones is a testament to that, especially in countries such as France and Germany.”

– former Director at Xiaomi Global (Source: Stream by Alphasense, 4/6/2021)

Although still early days, we think so far Xiaomi’s progress in premiumization is encouraging, and this is an important area for investors to track going forward.

Internet Services

Internet Services segment has standout profitability, as shown below. It accounts for less than 10% of Xiaomi’s total revenue, but generates about 40% of its gross profit, and an estimated 80-100% of its operating profit. This segment is the key monetization driver, but it also happens to be a tough one to understand as the company has provided limited disclosure (it’s the same thing with Apple, which also doesn’t like to talk about its Services segment)

Breakdown of services

Internet Services consists of three main areas: advertising, revenue share of in-app purchases (games), and other value-added services (subscriptions and fintech).

1. Advertising accounts for 65% of segment revenue, and is the fastest growing and also the most profitable component of the Internet Services segment. We expect the ratio of ads to go up over time. Advertising revenue breaks down into four types:

App store search ads: when users search for apps in the Xiaomi app store, it displays other ‘recommended apps’ alongside the search results (Xiaomi gets paid-per-download)

Pre-installation: Third-party apps pay to have their apps pre-installed on Xiaomi phones. This includes Ctrip, Netease, Dianping, iQiyi, Baidu, JD.com, and many others.

Display ads: Displayed in various Xiaomi apps - music, video, browser, shop, etc.

Outside of China, Xiaomi has ad partnership with Google.

2. Revenue share of in-app purchases accounts for 14% of segment revenue. Xiaomi takes a cut of the virtual currency spending on games downloaded through the Xiaomi app store or the Mi game center. The take-rate varies but is estimated to average at ~30%.

3. Other value-added services accounts for 21% of segment revenue. This includes paid subscription to content services including video, music, and online literature. It also includes revenue from fintech such as Mi Payment and Mi Credit. Note that margin here is comparatively lower, given the need to source subscription content (video, music, etc.) from partners.

China vs. overseas

The key insight here is that Xiaomi has a much higher attachment rate of Internet Services revenue for its China operations compared to overseas. China quarterly ARPU for services is at RMB45.9, compared to RMB4.1 overseas – that’s a 10-fold difference! The gap between overseas and China monetization is mainly explained by the higher usage of Xiaomi’s app stores in China (recall that Google Play store is banned in China for Android devices). This opens up the door to Xiaomi being able to monetize the app store in the ways we mentioned earlier, through app store search ads and revenue share on in-app purchases. As you can see, having an app store that’s widely used is crucial to services monetization. In addition, China also enjoys higher sales of other ad types such as fees from pre-installation, and also higher subscription revenue for its content services including music, video, and literature.

Overseas monetization potential

When we spoke to other analysts and buy-side investors, it seems most are still not yet sold on Xiaomi’s ability to monetize their overseas services. “Show me” was the general response. Given the unique challenges like lower app store usage, we don’t expect overseas monetization to reach China levels anytime soon. Having said this, the idea that Xiaomi can’t grow services overseas may also be an old belief that needs to be challenged, as recent results have demonstrated (below chart). There could be a potential bull case to be built here.

Xiaomi has started to disclose its overseas Internet Services revenue recently, and as we can see below, the growth has been accelerating over the last few quarters. Overseas Internet Services revenue is now 19.9% of total Services revenue, up from 12% last year.

Below, you can see the substantial growth in Xiaomi’s overseas services ARPU (albeit from a very low base). Overseas MAU has also increased rapidly. When we multiply these, we see that Internet Services revenue has more than doubled over the past year. Meanwhile, China services revenue “only” grew 16% (with flat ARPU).

In understanding the key drivers of future overseas ARPU growth, we think there are several important areas to pay attention to. Given the limited information available, admittedly we don’t have the full view into each of these yet, and are watching them closely to learn more.

First, the ongoing impact from Apple’s iOS 14.5 release must be noted. It has affected the ability for advertisers to use tracking data, negatively impacting ad ROI across iOS devices. As a result, there has been a trend of advertisers shifting their spending out of iOS, as the below chart shows. We believe this has led to increased ad demand on Android/Xiaomi devices, pushing up ARPU.

Second, the growth of Xiaomi’s consumer apps overseas. In China, the market has consolidated around powerful local tech giants like Tencent and Alibaba which dominates many verticals from entertainment to payments. Xiaomi has shifted its focus on overseas markets, particularly in emerging markets where category winners have yet to be established. Some of Xiaomi’s popular apps overseas includes App Vault (Convenient feature with short cuts and tools) with 230m MAU, Mi Video with 193m MAU, Mi Music with 145m MAU, productivity tool Mi Drop with 100m+ downloads. Also Xiaomi has rolled out fintech apps in India with Mi Pay and Mi Credit. These services can monetize directly (fees, subscriptions, etc.) and also provide inventory for ad placement.

Third, Xiaomi has an ad partnership with Google outside of China. Management has not provided any information on the details/scope of this partnership, but the company disclosed that its overseas search revenue has increased by 200% yoy in 3Q21. The importance and clout of Xiaomi as an ad partner should grow as the company executes its hardware market share gains globally. Its ability to turn its hardware share gains into increased ad sales momentum is something that may not yet be fully appreciated by the market.

China

We see a tougher near-term landscape for services monetization in China, as the regulatory crackdown takes its toll on the gaming and advertising sectors. With gaming play time being curbed for minors, in-app purchases could come under pressure. Advertising growth will also take a hit from crackdowns impacting various sectors from gaming to education to real estate.

While there will certainly be pressure near-term, we believe the long-term outlook for China’s Services monetization isn’t so bad. A breakdown of walled gardens and a check to the power of the large platform businesses, which the recent spate of regulations targets, could help to balance out the power dynamics in the industry. Keep in mind that Xiaomi is the top-of-the-funnel player, which should stand to benefit from there being more competition (=ad spending) among consumer services to reach the end users.

The Internet Services segment has a long growth runway on the advertising side. However, there is also a potential dilemma in this model – does advertising growth conflict with Xiaomi’s premiumization drive? So far Xiaomi has executed on both, but how sustainable is this model? It seems though that this is not a problem unique to Xiaomi, as we’ve seen Apple recently start to monetize its ad business more aggressively. With its app store economics increasingly under global regulatory scrutiny, Apple needs to find new avenues for growth, and advertising is one. Apple seems to be trying to figure this out “from above”, while Xiaomi is trying to do so “from below”.

Geopolitical risk

For a Chinese hardware maker growing globally, geopolitical risk is always top of mind. We can look at this in two ways: US-related and local jurisdictions.

First, in terms of US risk – Xiaomi doesn’t actually sell phones in the US, but as we know the US has the power to dictate global supply chains and investment flow. In January 2021, Xiaomi was accused of being affiliated with the military and placed on the US Department of Defense (DoD) blacklist. This meant US investors would be prohibited from investing in the company. Xiaomi subsequently sued the US government and won the case, and had its name removed from the list.

However, the bigger worry is the Department of Commerce (DoC) list, which could bar Xiaomi from access to critical US tech (the same one imposed on Huawei and ZTE). Xiaomi operating system is based on the Android OS, and it also relies heavily on Qualcomm as its main chip supplier. According to our knowledge, Xiaomi is a pure private sector business with no state-ownership, and founded by an entrepreneur with no known ties to the military. Arguably, this makes it different from Huawei or ZTE, whose military ties were essentially open secrets. We don’t think a strong case can be made for sanctioning Xiaomi, and the fact that the company was able to fight its way out of the DoD list was encouraging. Nonetheless, these things can be arbitrary, and if there is one thing that might keep Lei Jun up at night, this is probably it.

Xiaomi is also subject to geopolitical risk in the individual regions it operates. This is case-by-case depending on the region, but we’ll focus here on India given the importance of the market. How to think about the nuances of geopolitics risk in India?

First, nationalism and anti-China sentiment is real, and we need to keep in mind it will always be there. However, it’s also nothing new. There’s been growing calls for boycotting Chinese products, especially every time following instances of India-China border clashes which have occurred with frequency in recent years. But that hasn’t dented Chinese smartphone players’ market share in India. The top four Chinese brands (Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo, Realme) accounts for more than 60-65% of Indian smartphone volume and this hasn’t budged. There simply isn’t much of an alternative for mass market phones.

In addition, from early on Xiaomi has aligned itself with the government’s made-in-India initiative. According to an India-based former employee of Xiaomi who handled India’s procurement and vendor management for all after-sales:

“The other big advantage of Xiaomi which it has in mobile is that 100% of all the components are getting manufactured in India so that we give to the customer things that are made in India…We do manufacture all of our TVs and mobiles within India. We sell it for India. It is all made for India. That’s how we give confidence to the customer in terms of product”

– former Project Head at Xiaomi India (Source: Stream by Alphasense, 5/10/2021)

We have seen other sources which estimates the percentage of components made in India to be ~75% for Xiaomi. Perhaps the difference is in the way they recognize some items or define manufacturing vs. assembly. But regardless of the exact number, we know that it’s high and accounts for the majority of the bill of components. The same expert has stated:

“Today all put together, both on-roll employees and off-roll employees, in Indian office as well as the manufacturing unit, the after-sales service centers, all put together, there are 50,000+ employees which is getting employed directly and indirectly through Xiaomi India.”

– former Project Head at Xiaomi India (Source: Stream by Alphasense, 5/10/2021)

We think Xiaomi has been very savvy in its deep localization strategy, mitigating the geopolitical risk.

However, this also doesn’t mean they are totally immune. In 2020 India banned 220 Chinese apps which included Xiaomi’s Mi Browser. Soft bans such as this which targets apps can affect Xiaomi’s ability to monetize on the services side. From the Indian government’s point of view, this works better than banning hardware - let the Chinese makers sell cheap hardware for the benefit of consumers and the Indian supply chain. But the government has no reason to not be strict on the data/apps side, making sure there is a complete wall between India and China operations of these companies. Xiaomi claims 100% of its Indian user data stays in India. If there are lapses to this, then the consequence could be big.

Aside from India, Xiaomi is geographically well diversified and no individual country accounts for a meaningful enough portion of sales. Most of the other countries Xiaomi sells to are not geopolitically at odds with China. Importantly Xiaomi has little to no sales in the main Anglosphere countries (US, UK, Australia, Canada, and Japan), where as far as geopolitics is concerned would be the highest risk.

Electric Vehicle

In March 2021, Xiaomi announced its entry into electric vehicles. Xiaomi expects to showcase a prototype by the end of 2022, and start mass production in the first half of 2024. Our friend and keen EV sector analyst Yilun pointed out the following relevant questions (give him a Twitter follow @yilunzh) -

Will Xiaomi be too late? By the time Xiaomi comes out with its first vehicle in 2024, the bar for what a successful EV entrant must do will be dramatically higher, both in terms of battery tech/range, autonomy, and charging infrastructure. There are still two more years left until Xiaomi rolls out its first production vehicle (and that’s assuming without delays). Rivals Nio and Xpeng launched commercially in 2018 – that’s six years of iteration and learnings ahead of Xiaomi. Can a late entrant bridge this gap?

Xiaomi has committed to an initial investment of US$1.5bn, and total of US$10bn in 10 years. Will this be sufficient? It depends on to what extent Xiaomi intends to outsource vs. do things in-house. These sounds like big numbers, until you look at how much other new EV brands have spent to get to market. Nio raised $2.3B prior to first delivery and didn't even have to invest in a factory.

What’s unique that Xiaomi brings to the table? What can a phone company bring to EV? There really isn't any path where Xiaomi can take a shortcut to overtake competition. Retail presence and brand awareness helps, but that only goes so far. The important things are vehicle engineering, manufacturing capacity, supply chain, charging network and service network, all of which Xiaomi will also have to build from scratch.

So the short answer is, it’s hard to pinpoint anything at this stage, and perhaps investors have the right to remain skeptical. Put it this way - if you want EV exposure you shouldn’t be investing in Xiaomi to do so. Just go straight to Nio, Xpeng, or the other EV players (that actually have products and revenue). For Xiaomi investors, it’s really a bet on Lei Jun at this point. Notably, Lei Jun is spearheading the EV efforts himself, and has said that this is likely going to be his last big career endeavor before retirement.

Valuation

When modeling Xiaomi, a word of caution is to not use the reported income figures (operating line and below), which includes profit and losses from Xiaomi’s investment portfolio (fair value changes, disposals, dividend). This needs to be adjusted in order to obtain an accurate picture of the underlying business. After adjusting, operating profit looks like below – we see a margin expansion trend, driven by gross margin expansion in smartphone and services (note the large one-off administrative expense in 2018 was due to share grant to employees prior to the IPO)

We derive our estimated FY24 net income of RMB31b, based on the following main business assumptions:

Xiaomi achieves its handset volume goal of 270m, at ASP of RMB1,227 (5-6% CAGR). Attach rates stay consistent within historical range for IoT and Internet Services.

Continued margin expansion of Smartphones and Internet Services, driven by handset premiumization and ad growth, reaching gross profits of 15% and 80% respectively. IoT margin sees no growth.

Operating expense-to-sales ratio stays constant at current level of 12%, which is already best-in-class (Apple is 12%).

Effective tax rate of 25%.

In the chart below, we illustrate two valuation cases (constant multiple and multiple expansion). Note that the chart is in HKD. Xiaomi reports in RMB, but is traded in Hong Kong. We need to work with one currency – we’ve chosen HKD here.

Xiaomi’s current net income multiple on EV is 13.4 (taking into account the company’s sizable net cash and investment portfolio, we use EV). A low-teens multiple is basically saying Xiaomi is valued like a typical consumer electronics maker. Recall Apple’s multiple stayed in the low-teens range for much of the early 2010’s (and it wasn’t until 2016 that the multiple sustainably exceeded mid-teens). Assuming we see no multiple expansion and use the current multiple on our estimated FY24 earnings of RMB31b (HKD$38b), we derive end-of-FY24 share price of ~$24.

In the second case, we assume margin expansion to 20x p/e. This would be consistent with investors buying more into Xiaomi’s services monetization story, and perhaps starts to value Xiaomi on multiples consistent with the digital advertising giants (Alphabet/Meta). In this case, our share price target is bumped to ~$32.70.

Taking a range between these cases, our 3-year CAGR target is 13-26%.

Concluding thoughts

When we look at Xiaomi, we see a relatively young company that still sees its own journey as day one. We believe it is executing on the right path to building out unique advantages and ‘moats’ across multiple fronts. Investors are buying in Xiaomi:

Lei Jun and the culture of "a smart and resourceful underdog” that he’s cultivated, whose track record speaks for itself. Lei Jun is 52 years old, so he’s still got runway ahead.

Global brand that has become synonymous with value-for-money, while at the same time moving up the value curve.

Unique ecosystem strategy, driving successful product category expansion and the growth of multiple-product users.

Improving distribution footprint, both at home (offline store growth in China) and overseas (new carrier relationships)

Growth in services monetization, as the company turns hardware growth momentum into advertising share gains.

Efficient operator with the best-in-industry cost structure.

Stream by Alphasense is an expert interview transcript library that has been integral to our research process. The quotes we used in this research were sourced from Stream. They are a fast growing expert network with over 10,000 transcripts on a wide variety of industries (TMT, consumers, industrials, real estate and more). We recommend Stream for its high quality transcript library (70% of experts are found exclusively on Stream) and easy-to-use interface. You can sign up for a free trial by clicking here.