Summary

Rakuten is Japan’s leading e-commerce and online consumer services company. Despite its dominant and growing core business, shares have underperformed and trades at a substantial discount.

We believe this is caused by the substantial investments associated with the company’s entry into the telecom business, which investors regard as being capital destructive. But in our view, the pessimism here is overdone.

We outline the business case for the telecom business and the potential for narrative change, driven by improving economics together with its strategic benefits and growth optionality becoming more apparent over time.

Rakuten is a “value” play, but with the unique opportunity that the core of the company is a growing consumer tech asset with a long growth runway.

Our 3-year target price is 2,200 yen for a 24% IRR (range: 7-38%).

If you are interested in a non-consensus long idea which lies at the intersection of value and tech, read on to learn more!

Introduction

Rakuten operates Japan’s largest e-commerce marketplace, called Rakuten “Ichiba”. The company is also a major player in financial services, which spans banking, credit card, payments, securities brokerage, and insurance. Rakuten is a dominant online consumer services empire, with the core of the company being a synergistic ecosystem comprised of e-commerce and financial services. While we have seen other companies around the world adopt this “e-commerce + financial services” model (e.g. Alibaba), Rakuten actually long pioneered this model before anybody else, and has been operating this model successfully in Japan for more than a decade.

The below chart gives you a sense of Rakuten’s scale and where it stands relative to the other major e-commerce platforms of the world. If you’re like me, your initial reaction when you see this might be: “$16 billion for the leading e-commerce platform operating in the world’s third largest economy…what’s going on here?” You might also scratch your head a little when you see South Korean Coupang, which trades at $46 billion and is almost 3x Rakuten (knowing South Korea has just 40% of Japan’s population). Hmm…

Rakuten’s “core” is on track to generate about US$1.4 billion of operating income on $11 billion of revenue this fiscal year, while growing the business in the mid-teens. It enjoys a long growth runway in the Japanese market. Considering this part alone, no matter how you want to look at it, a valuation (market cap) of $16 billion seems unusually cheap. So this begs the question – what seems to be weighing down the shares? To answer this, we need to go back a few years. In December 2017, Rakuten made the groundbreaking announcement that it planned to become a MNO (mobile network operator), in a bid to challenge Japan’s three-player telecom oligopoly. An e-commerce company getting into telecom – never heard of this one right? We’ll explain this in detail later and help you understand the company’s thinking behind this unusual move.

But as you can imagine, the spending required for entering the telecom business (Rakuten calls it mobile business, we’ll use the terms “mobile” and “telecom” interchangeably) is substantial, and this has pushed Rakuten into loss-making territory on a consolidated basis. Most investors were not a fan - “Why the heck is Rakuten doing this?” “Why not just focus on the core businesses which are profitable and growing?” Rakuten’s share price today remains the same it was four years ago, weighed down by the spending in its new mobile business, despite the continuing strong performances on the e-commerce and financial services side of the company.

Investors remain skeptical to this day, but we believe now is a good time to revisit the company. The strategic benefits of the mobile business are beginning to show. Synergy with the company’s core is being delivered, while the recent major partnership deal with Germany’s 1&1 is a validation of Rakuten’s technology and its global monetization potentials ahead. Looking at the economics of the mobile business, there are reasons to believe losses have hit its worst point and should improve going forward, as the business is moving past the heaviest phases of user/network subsidies. Re-rating could be in sight as the narrative surrounding the mobile business improves. Meanwhile, there is much to like with Rakuten’s core e-commerce and financial services ecosystem, which remains highly dominant and is poised to grow alongside Japan’s long runway of retail and financial digitization in the decade ahead.

Historical context

Rakuten was founded by Hiroshi Mikitani (“Mickey”), a former investment banker at the Industrial Bank of Japan. Mickey obtained his MBA from Harvard in 1993. Having been inspired from his time spent in the US, Mickey decided to embark on an entrepreneurial journey upon his return to Japan. In 1997 he founded Rakuten as Japan’s first online marketplace.

The history of Rakuten can be roughly broken down into three parts. The first part is the founding and establishing of the Rakuten consumer ecosystem. After establishing “Ichiba” in 1997, Mickey set out a path to make his company much more than just a goods marketplace. In 2001 Rakuten Travel was established, which has grown into one of the two major OTAs (online travel agency) in Japan. In 2002, Rakuten Points program was established, which today is the largest consumer rewards program in Japan. Rakuten branched out into financial services, entering banking, payments, and brokerage businesses by acquiring established players and then re-branding and integrating them. In this way, Rakuten became the pioneer as a builder of a diversified online services ecosystem.

The second part of Rakuten’s history is defined by its internationalization efforts starting in the early 2010’s. In a fashion typical of Japanese firms trying to grow overseas via acquisitions, this was mostly a failed effort. In 2010 Rakuten expanded into Europe through acquisition of PriceMinister (EC business in France), followed by a streaming player in Spain called Wuaki. In North America it acquired e-reader company Kobo (2011 for $315 million), streaming player VIKI (2013), and shopping rewards company Ebates (2014 for $1 billion). It also acquired the Luxembourg-based communications company Viber (2014 for $900 million). We won’t get into the details on each but suffice to say that most of these acquisitions have disappointed. The good news is that management seems to have had enough, having abandoned chasing overseas consumer tech acquisitions since 2014 (after years of racking up losses, Rakuten disclosed in the most recent quarter that profits at these overseas businesses have finally turned around to a point where it’s now nearing breakeven).

But there was actually also something positive that came out of all of this internationalization drive. In 2012, Rakuten made English the official company language. If you’re familiar with Japan, then you’ll know that this is no ordinary business decision! In fact, it was seen as crazy at the time, met with plenty of criticism and skepticism from both inside and outside the company. Today, 25% of Rakuten’s employees are non-Japanese, which is the highest of any Japanese tech company. While it led to a painful period of cultural adjustment at first, the visionary nature of the “Englishnization” move is becoming increasingly apparent over time, as Japan grapples with the problem of aging demographics and a shortage of skilled IT personnel. Mickey saw the increasing need for overseas talent, not just to fill the labor shortage, but he recognized that the best tech companies should be able to attract the best workers from around the world. This kind of decision making should give investors some insight into the kind of leader Mickey is - he’s a maverick, and is not afraid to make bold strategic decisions.

The third part of Rakuten’s story is where we are at today – expanding into the MNO business. In 2018, Rakuten was granted telecom license by Japanese government to build out its network. In the same year, Rakuten hired Tareq Amin, the current CTO and the key man behind the mobile business. Prior to Rakuten, Tareq was the Sr. VP at Reliance Jio (India’s largest carrier) where he focused on technology development of next-generation networks. Rakuten launched service using its own network in March 2020, and as of October 2021 has signed up more than four million subscribers and achieved a nationwide 4G population coverage rate of 94% in Japan.

Rakuten Core

Let’s first talk about the core of the company - the high conviction part which investors can fall back on.

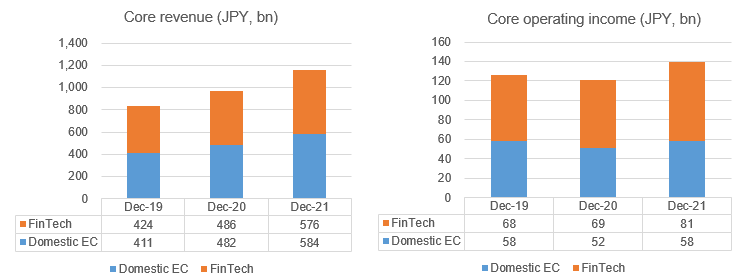

The core of Rakuten comprises of two parts – Japan domestic e-commerce and financial services (note: the company uses a sexier name for this - “FinTech”). The below graphs shows the revenue and operating income breakdowns and trends:

The domestic e-commerce segment is comprised mainly of Rakuten “Ichiba” marketplace, the company’s flagship B2C marketplace. The marketplace is primarily monetized on a “fixed + commissions” model, in a way similar to Alibaba’s T-Mall ($200-1000/month + 2-7% of sales). In recent years Rakuten has been ramping up investments into logistics, trying to build up its own logistics support for merchants in a similar fashion as FBA (Fulfillment by Amazon).

Included in the domestic e-commerce segment is the advertising business which accounts for ~20% of segment revenue. Rakuten claims it has roughly 55% share of ads on e-commerce platforms in Japan. Much of this comes from internal inventory (Ichiba and others), however the ad business is positioned as an independent business unit which also handles external inventories. Also included in domestic e-commerce are Rakuten Travel, Rakuten Seiyu Netsuper (online grocery), Rakuten Books, Rakuten Fashion, and Rakuma (used goods C2C marketplace).

Rakuten’s GMV is on track to hitting 5 trillion yen (~$44 billion) this fiscal year, which gives it a respectable 25% market share in Japan’s 20 trillion e-commerce market. Rakuten GMV has grown at 12% CAGR over the last five years, outpacing the broader Japanese e-commerce market growth rate of 8-9% (source: METI). With Japanese e-commerce penetration at only 8% (vs. China 20%, South Korea 19%, and US 12%), the runway for growth is still long.

On the financial services side, the below chart illustrates the breakdown of services. Rakuten is the largest credit card issuer in Japan, with 24 million total cards issued (Visa, Mastercard, AMEX, JCB). It’s also the largest online bank with 11 million accounts (side note – company is now preparing for an IPO of Rakuten Bank). They also have sizable presences in online brokerage (6.7 million accounts), online insurance, and a payments business including E-money (Edy) and mobile/QR code payment through Rakuten Pay. For consumers, Rakuten can take care of all of their financial needs without having to leave the ecosystem.

A major growth driver for Rakuten’s financial services portfolio is the growth of cashless payments in Japan. You may already know that Japan has one of the highest reliance on physical cash usage among developed economies (Japan’s cashless payment ratio is in the 20% range, versus developed country average in the 40-60% range). The Japanese government has designated the advancement of cashless society as a strategic priority, and established a goal of 40% cashless payments ratio by 2025. Rakuten is singlehandedly responsible for roughly 20% of Japan’s cashless transactions through its credit cards and other payments offerings, and is well-positioned to benefit as a royalty play on Japan’s financial digitization.

Now let’s talk about how all of this fits in together under Rakuten’s unified consumer ecosystem. All of Rakuten’s services are accessed by a single user ID, and as of September 2021 there were 125 million registered IDs (roughly equal to Japan’s population). Service cross-usage is significant in the ecosystem: 74% of users use two or more Rakuten services, and this has been growing (was 68% three years ago). Notably, over 70% of Rakuten credit card holders shop on Ichiba marketplace, and in turn 69% of Ichiba GMV was generated by Rakuten credit cards. The ecosystem works.

The glue that holds all of this together is the Rakuten Points rewards program. If you know anything about Japanese consumers, it’s the fact that they absolutely love their points (side note: decades of deflation may have contributed to this mindset). Consumers treat Rakuten points like cash, because they are highly versatile. Points can be used within Rakuten’s service ecosystem, but also offline at a large number of restaurants, department stores, and supermarkets. You can even buy investment products (stocks, cryptocurrencies) with them. The rewards program is structured in a way so that the more services that are used in the ecosystem, the bigger the point “multiplier” becomes which incentivizes cross-usage.

As you can guess, these points are a significant expense item, which last year amounted to 100 billion yen or 7% of consolidated revenue (the actual amount of points rewarded is even greater because accounting cost is calculated based on estimated usage. Only a portion of points is used while the rest is deferred). Rakuten’s vibrant ecosystem is a moat which makes the company more robust compared to any single-business line competitors. Points expenses should be regarded as the business cost of sustaining such a moat.

Mobile business

So now we get to the more controversial part of the company.

Let’s first understand the backdrop behind Rakuten’s decision to enter the mobile business. It starts with recognizing that for years, mobile pricing in Japan has been the subject of public discontent. A report by the Japanese government showed the Japanese spent 3.7% of household expenditure on telecom expenses, which was the fourth highest among OECD countries (vs. Korea 3.1% and US 2.5%). Surveys have shown that many Japanese viewed their telecom industry as predatory and unfair. The issue was further escalated in 2018 when Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary publicly denounced the telecom industry and stated “carriers should be able to cut their prices by 40%”. This kind of rebuke by a high-ranking politician was unprecedented, and showed the extent to which public discontent was a real issue. The government was willing to support a fourth player that could disrupt the industry’s cozy status quo.

It was under this backdrop that Rakuten decided to enter the industry. Mickey felt that if anyone was going to do it, it would be them. He believed that by entering this business, Rakuten could actually achieve not one but three business opportunities, which he called “hitting three birds with one stone”. Here’s a brief summary, which we will dissect later on. Basically,

First, they’ll challenge the industry status quo by offering the most disruptive pricing plan. To do so, they’re going to build a low-cost network from scratch, leveraging new industry technology to build and operate the world’s first fully virtualized open-RAN network;

The mobile business will expand the sphere of Rakuten’s consumer ecosystem, and deliver synergy by capturing users at the top of the funnel and directing traffic into all areas of Rakuten’s services ecosystem. This in turn allows the mobile business to be further subsidized; and

Rakuten will monetize its network building experiences and knowhow by opening up its technology to telecom operators around the world (this is inspired by Amazon’s AWS model)

And with this, Rakuten got down to constructing its network, and commenced full-scale service using its own network in March 2020. They’ve kept their word in offering the industry’s most competitive pricing. Rakuten’s plan provides better value for consumers under almost all usage conditions. For light users (3-20GB monthly), Rakuten charges 1,980 yen versus the discount brands of the big-3 which charges 2,480 and 2,700 yen. For heavy users (unlimited data) the big-3 charges around 6,550 yen while Rakuten is priced at only 2,980. Rakuten is providing savings of 20%+ for light users and 60%+ for heavy users.

Technology

Rakuten claims to be the first company in the world to build and operate a “fully virtualized open-RAN network” (ok that’s a mouthful). The premise is that it’s designed to make things lower cost by tackling the bloatedness of the telecom industry status quo. Rakuten couldn’t be more bullish on this technology - just look at the statement by CTO Tareq Amin:

“My belief is this platform is going to change everything…(it’s) going to change the ecosystem of telecommunication in this country and across the world.”

Wow, ok. But what does it actually involve?

Let’s first understand the basic pain points in the traditional telecom supply chain. To build a network, you need sophisticated communications hardware placed at base stations at the nodes of a network. Traditionally, these were “proprietary boxes”, and the vendors (usually Nokia and Ericsson in developed markets) had full control over the hardware and software stacks. Operators are locked into procuring these from a single vendor, as the equipment are typically not interoperable, resulting in networks that are expensive to build and inflexible. The premise of open-RAN networks is that as the name suggests, the system is opened up and “unbundled”, allowing products from different vendors (both hardware and software) to be mixed and matched, resulting in cost optimization.

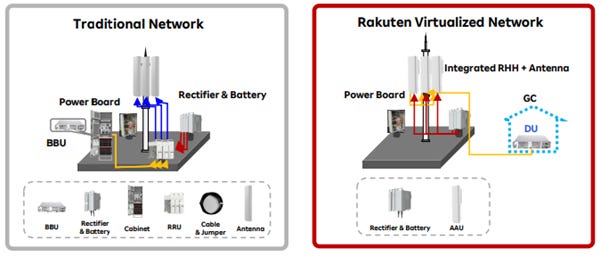

But open-RAN is more than just about this unbundling. It’s also about reconstructing a more efficient network that reduces hardware redundancy. See below diagram for the base station hardware setup at a traditional network compared to Rakuten’s network. Consider the Baseband Unit (BBU), which is a core computing hardware component of the base station (its function is to determine the “capacity” of the system). Under a traditional network, BBU is required at every base station. But Rakuten’s virtualized network allows for base stations to be built without the BBU. A single BBU can be run from a centralized location, which connects to dozens of nearby base stations, and allows for computing resource to be scaled up/down dynamically as needed.

Essentially what this is doing is putting BBU on the cloud. If you’ve been following until here, you are probably reminded of what hyperscalers did to enterprise IT (AWS, Azure, GCP). And that’s the kind of transformation which this promises to bring to the telecom industry. You don’t have to take my word for it, but this is what Pat Gelsinger, Intel’s CEO has to say regarding the technology:

“This is as industry-shaping as the cloud environment was 20 years ago when we first laid the architectural seeds for it. I don’t think there is anything that can understate the significance of what Rakuten has done here…how can you replicate what Rakuten has done around the world? Because this is the way every network will be built in the future.”

So what does all of this accomplish from a financial point of view?

40% reduction in network capex. For a traditional telco network, the cost mix is roughly 30% software, 45% hardware, and 25% deployment. For Rakuten’s network, the cost of software remains at 30%, but hardware cost can be reduced by 60%, and deployment by 50%, resulting in overall 40% savings.

30% reduction in opex. This comes from reduced power consumption, reduced maintenance/site visits, and reduced site lease fees, all due to the lower hardware footprint. Traditional networks require one engineer per 1,000 subscribers, while Rakuten’s network only requires one engineer per 20,000 subs.

You may be wondering - if this technology makes so much sense, then why haven’t most existing telcos adopted this already? Indeed, most industry experts seems to agree that the industry technological roadmap is headed towards this direction of openness and virtualization. However, adoption takes time. Think of why conservative enterprises, such as banks, can stick to using their legacy systems for ages even long after it has ceased to be competitive. Telcos are averse to swapping out parts of its networks, as to avoid the risk of upsetting its service. Also, legacy vendor dependencies and relationships are in place. The ability for disruptive players like Rakuten to come into the industry and build a new network from scratch, unencumbered by the burden of legacy assets is a real advantage. It fits into the pattern that oftentimes disruptive opportunities exist precisely thanks to the fact that incumbents have vested interest in not changing. This is also why the early adopters of this new technological framework will likely not be the traditional telco players, but rather the new entrants or emerging market players who have a greater need for lower cost and more flexible networks.

Synergy with the Rakuten ecosystem

Every consumer tech company has the desire to own top-of-the-funnel. This is the reason why Microsoft and Google makes phones. Google pays Apple enormous amounts of money to stay the default search engine on iOS, but still decides that it has to make its own phones. Also, Facebook makes AR glasses and the Oculus hardware. For Rakuten, even though the firm doesn’t make hardware, the logic is similar as mobile plans represents top-of-the-funnel user capture. Phone plans are typically very sticky, as people don’t switch their plans easily. It represents a captive set of users that Rakuten can direct towards all areas of its online services ecosystem.

Cross-pollination has been happening significantly between the mobile business and the rest of Rakuten ecosystem. Mickey has stated:

“There have been more contributions to the ecosystem than we initially thought. In fact, so beneficial that we had to ask ourselves if it was real”

Rakuten has the numbers to back this up. Consider: 19% of new mobile sign-ups (March to September 2020) were by users who had never previously used any Rakuten service. These users, within 6-12 months of signing up to mobile,

1 in 3 users started using Ichiba (marketplace) for the first time;

1 in 5 users signed up for a Rakuten credit card;

1 in 9 users became an online banking customer;

1 in 10 users started using Rakuten’s other payments solutions;

This is quite impressive - it means between 33 to 74% (depending on the overlap of cohorts above) of new mobile users were directed into the Rakuten ecosystem for the first time. What’s also impressive is when we look at new mobile subscribers who were already existing Rakuten users - after signing up for mobile, these existing users increased their purchase value on Ichiba marketplace by 60%. It looks to me that the synergy is well quantified and significant.

Monetization strategy (global)

Rakuten wants to monetize its network building experience and knowhow. “Rakuten Symphony” is the new company which has been established to serve any telco player in the world that wishes to implement Rakuten’s network technology. Depending on customer preference, Rakuten can provide just the open-RAN software on its own, or provide full end-to-end integrated solution. Rakuten struck a partnership with the US-based open-RAN system integrator Altiostar in 2019, whereby Rakuten became a minority investor and also used Altiostar software for its own network. Two years later, Rakuten completed a full buyout of Altiostar, bolstering its capability to serve external clients. Altiostar is now part of Rakuten Symphony, and has brought along its global client list which includes Dish, Bharti Airtel, and Telefonica. Rakuten has also partnered with Tech Mahindra, one of India’s largest IT services firms, to provide global system integration capability.

Ever since Rakuten Symphony was established, the first major business win came in August of this year with Germany’s 1&1. 1&1 is in a similar position as Rakuten, where they are the low-priced entrant challenging Germany’s established three player telco oligopoly. Rakuten secured a 10-year contract to build/run/maintain 1&1’s network, at an amount undisclosed but leaked by some sources to be $2.3 billion. According to 1&1, they chose Rakuten as a partner, as Rakuten not only has the relevant technology, but also the experience in running a virtualized open-RAN network as an operator, differentiating it from the other pure technology vendors.

According to Mickey,

“The incremental cost of delivering the 1&1 network is low, due to investments already made in Rakuten RCP (Rakuten Communications Platform) and establishing Rakuten Mobile”

and that the 1&1 contract will be profitable from the start. But the significance of the 1&1 deal is not just the economics, but perhaps more importantly the fact that it’s an external validation of Rakuten’s technology (turns out they probably weren’t just bluffing!)

Rakuten Symphony claims they’ve identified over 100 prospective customers globally which they are currently in discussions with. The company places the estimate of its addressable market at north of $100 billion (make of it what you will). One telco industry engineer that I’ve spoken to believes the timing is an opportune one, as Huawei (the industry’s low cost vendor) has been banned from North America and most of Europe, leaving operators in these regions without much vendor options other than the costly Nokia/Ericsson. The timing could be a great one for smaller disruptors like Rakuten to be proposing more cost-effective alternate solutions.

Mobile economics

Now that we’ve discussed the technological and strategic angle behind the mobile business, it’s now time to look at the financials side (see below chart). Let’s see…a massive sea of red, as expected! Looking at this, it’s not surprising that investors have shunned this company. Because at first glance, it seems disastrous. Ever since they started the mobile service in March 2020, revenue has barely grown while costs have soared. The business seems to be hit by a double whammy of little-to-no topline growth and expanding cost. What’s happening?

Let’s look at topline first. You might think it’s odd that topline hasn’t grown - after all, haven’t they been increasing mobile sign-ups? One needs to pay attention to two dynamics at play here. First is the free promotional period. For new subscribers with start date between March 2020 to March 2021 Rakuten offered a very generous one-year free contract (From April 2021 onwards they’re offering 3 months free instead of one year). In particular, a large number of new subs were added in the last three months (Jan-March 2021) due to the last-minute demand prior to the conclusion of this one-year free campaign. These subs won’t start paying until one year later, which is starting 1Q 2022. Therefore, a boost to revenue should actually just be right around the corner.

Another point to keep in mind is that Rakuten has been offering mobile service under an MVNO since 2014 (utilizing NTT Docomo network), prior to launching on its own network. When they launched their MNO, they stopped offering MVNO and converted existing MVNO into MNO customers, which resulted in revenue cannibalization. This MVNO to MNO conversion has mostly happened already, as MVNO subscribers are down to under 1 million, out of total 5.1 mobile contracts (which includes MVNO + MNO). Refer to the chart below (pink bar: MNO, grey: MVNO).

The question then is how well Rakuten can retain its users after the free usage period. Unfortunately, Rakuten doesn’t disclose the churn (and perhaps this can be taken as the fact that churn is not where Rakuten wants it to be yet). Indeed, a look at local online user reviews still shows the main complaints being poor connectivity in certain locations, and this seems to be the biggest reason behind cancellations. Having said this, Rakuten Mobile is still ranked as the #2 most popular discount SIM on Kakaku.com, Japan’s largest consumer review website. And it does offer undeniably the most competitive pricing in the industry. As the network quality matures over time, churn should be expected to improve.

Cost, capex, breakeven

Costs have ballooned, but there are reasons to expect cost pressure to ease going forward. This is because the biggest contributor to cost increases has been the roaming charge which Rakuten pays KDDI (Japan’s second largest telco). You see, Rakuten couldn’t simply wait to build out its network completely before starting its commercial service. So Rakuten contracted with KDDI and borrowed one of KDDI’s spectrums (800MHz LTE) to cover users for areas where it didn’t yet have adequate coverage (especially in underground areas and certain commercial buildings).

Rakuten doesn’t disclose its payments, but using KDDI’s disclosure investors can actually back out how much Rakuten is paying in roaming charges. In the most recent quarter (Jun-Sep 2021) Rakuten paid ~36b yen to KDDI (34% of its mobile losses of 105b). The total cost of mobile business increased 40b over last year, out of which half of this was due to increase in roaming charges to KDDI! There are reports that Rakuten is paying KDDI ~500 yen per GB of roaming, for up to 5GB per user, or ~2,500 yen per user (this is nuts!) So obviously, if they can shut off this roaming payment, it will go a long way to improving mobile economics. Understandably, Rakuten has been building its own network at the fastest possible pace to become self-reliant. Management expects to be able to greatly reduce reliance on KDDI, once 96% population coverage is achieved by 2Q of 2022. From October, Rakuten has started to drastically reduce the KDDI roaming area in 39 prefectures by switching to its own network. Going forward, the shutoff of roaming payments should be a major driver for narrowing mobile losses.

How much more network capex is necessary? Consider Softbank, which is currently Japan’s third largest network (with 38m subscribers). Softbank has ~2.5tn yen of networking equipment on its balance sheet (taken at gross). If we take at face value Rakuten’s claim that it can construct its network with 60% less hardware intensity over traditional networks, then Rakuten’s equivalent network would only require ~1tn yen of hardware. Today, Rakuten Mobile has already invested ~800b of PP&E (gross), leaving only 200b additional capex left. They’ve been investing at a rate of over 100b yen per quarter, which will only require 2 more quarters of growth capex at the current rate (however, it requires noting that Rakuten does not yet possess the coveted “platinum band” spectrums, which could result in subpar capex efficiency relative to the 3-majors - this is explained later).

To get a sense of breakeven point for the mobile business, consider the current annual cost run-rate of 640b yen. We should adjust this by substracting out the KDDI roaming payments of 140b. To achieve independence from KDDI, Rakuten will require additional capex which we’ll assume as 200b from earlier, or 40b on the P&L (5 year depreciation). This results in an adjusted cost run-rate of 540b. To breakeven on this, Rakuten needs 400b of sub revenue and 140b of handset revenue (assumes handset revenue is ~35% of sub revenue, in line with Softbank). At 2,500 yen ARPU, that requires ~13m subs ( 7% of total 180m mobile subscriptions in Japan). Softbank has 38m subs as the smallest of the three majors, so Rakuten needs to get to 34% of that.

If we assume Rakuten could hit 3m net new subs per year (this represents a slightly accelerated sub growth, but they will also have the benefit of lower churn over time as the network quality matures), then breakeven could be achieved in 3 years on the assumed cost base.

As we examine the bigger question of what “success” looks like for Rakuten’s mobile business, it could perhaps be characterized as the following:

Continuing to generate quantifiable synergy with the core Rakuten ecosystem, with the benefit of this manifesting as the accelerated revenue growth on the e-commerce and financial services side over time;

Rakuten Symphony obtaining further contract wins globally, becoming a meaningful pillar of revenue generation on its own; and

While we could see a reasonable path for the mobile business to breakeven over the next few years, it’s still difficult to envision how this business could generate any kind of juicy returns on a standalone basis under the current trajectory. But that’s not necessarily what success has to look like, given the other avenues of value creation mentioned. I believe it’s a win for the company and investors, so long as the mobile business is able to become self-sustaining, and at the same time contributing positively to the rest of the ecosystem.

I believe the following are the main short to medium-term risks for the mobile business:

Difficulty in procuring networking hardware due to the ongoing semiconductor shortage, affecting pace of network buildout (delays to cut down on roaming payments);

Cutting down of KDDI roaming possibly resulting in meaningful deterioration of service quality and user experience due to poor execution;

Higher-than-expected churn of early subscribers, following the expiry of the free promotional period;

Slower-than-expected subscriber growth going forward and the petering out of topline before being able to reach breakeven

There is one last point on this business that needs a mention. Rakuten is currently lobbying the Japanese government to obtain the so-called “Platinum Band” of lower frequency spectrums (700-900MHz). Compared to Rakuten’s current 1.7GHz spectrum that it uses, these offer improved penetration enabling better area coverage and network quality. The big-3 operators all possess these prized spectrums, and Rakuten is making the case to the government that it too should have access in order to enable fair competition and to further bring cheaper and better services to the public. However, spectrum allocation is a controversial matter in Japan, notorious for being crony capitalism and the process being highly untransparent. With the big 3 on the other side pressuring the government to delay the re-allocation for as long as possible, it remains to be seen if/when Rakuten could be given the opportunity.

Regulatory

We believe Rakuten operates in a more benign regulatory environment in Japan relative to consumer big tech in other regions such as China (Alibaba, JD, Pinduoduo), United States (Amazon), and South Korea (Coupang). In fact, we see the role of the government being a net positive and a tailwind to supporting the company’s growth, particularly in financial services (digitization push) and mobile (disruption to the telecom status-quo) as we’ve discussed. The Japanese government has taken a comparatively light-handed approach in regulating its tech industry, in part given Japan’s already slow digital transformation relative to other major economies. Digitization has been a major policy goal by the government across all areas of the economy, and we believe this will remain a priority going forward. In a world where regulatory risks for big tech is generally of growing concern, Japan looks comparatively like a safe harbor.

Management

Founder and CEO Hiroshi Mikitani (“Mickey”) and family owns ~35% of the company. Mickey is a risk taker and he’s relentless. At 56 years of age and after running this company for 20+ years, he has decided to undertake the biggest challenge yet in disrupting the telecom industry. One can also see from his “English-nization” decision from ten years ago as another example of his unusual boldness as a leader.

While Mickey hasn’t been successful at everything, his drive and determination to make bold, long-term strategic decision for the business is an admirable one. Comments from former employees suggests that the culture of Rakuten is very much like that of an owner-operated company. Even at the size of the firm today, key decisions can be made fast, enabled by Mickey’s entrepreneurial style. Indeed, Rakuten is the only founder-led company remaining among major e-commerce companies in Japan, and former employees seem to acknowledge that this has been an advantage.

Investor should take note at Rakuten’s most recent capital raise in March (below diagram). Notably, Mickey and his family invested 10 billion yen (~$90 million) of their own money into the company. I can’t recall the last time I saw a CEO of a public company acquire this much shares of his own company through outright cash purchase, rather than with stock options (as they say, management may sell shares for various reasons, but they usually only buy for one reason). Investors ought to take note. Tencent’s investment (65.7 billion yen or ~$600 million) is also an interesting one, with this being Tencent’s only non-content acquisition in Japan.

Japan Post also provided a large capital infusion (150 billion yen or ~$1.3 billion) under a strategic long-term partnership, which encompasses all areas of Rakuten’s business. In e-commerce, Rakuten will expand its delivery to rural areas and utilize Japan Post’s logistics to do so, which frees itself from the burden of rural capex. Japan Post’s network of 24,000 post office locations are also a strategic asset for Rakuten, and the plan is to establish physical sales counters inside post office locations to sell mobile plans and Rakuten’s other financial services such as credit cards. In addition, Rakuten also plans to take advantage of Japan Post’s network density to set up base stations on the roofs of post offices to improve its mobile network coverage.

Valuation

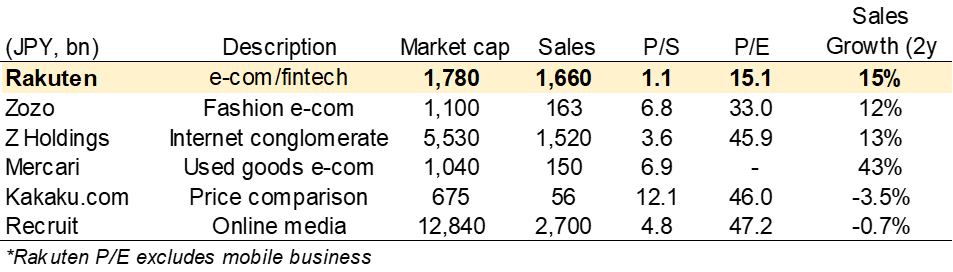

The comp chart below with Japanese internet sector peers suggests a pretty fully valued (if not inflated) sector, with Rakuten as the anomaly in the peer group. If we go by the comps and apply the peer group valuation of 30-40x on Rakuten’s estimated core after-tax earnings of 116b (excludes mobile), we get to a valuation of 3.5 to 4.6tn yen. The “discount” to current market cap of 1.8tn is substantial, at about 50-60%.

The following assumptions yields us 3-year IRRs:

We can be fairly confident on the sustainable and profitable growth of the company’s core, and assume a double-digit core earnings growth (10% even in the bear case), and a 25x multiple.

To put a value around the mobile business, use a range of 0-1.0x revenue multiple on estimated domestic telco revenue of ~540b in the third year (based on earlier calculation). Note: KDDI multiple ~1.4x revenue. The growth optionality overseas (Rakuten Symphony) is not included here.

Depending on the market’s narrative/sentiment surrounding the mobile business, we assume a discount of 50% persisting in the bear case, while we assume a partial and full elimination of discount in the base and bull cases respectively.

I would like to say that Rakuten’s discount seems exaggerated. But as with any “value” type opportunity, this is not to say that the stock can’t de-rate further from this point onwards, which is why having conviction around the improving narrative for the mobile business going forward is important. In such case, Rakuten may have a compelling place in the portfolio of medium to long-term investors who are value-conscious, yet still want to ensure that they own quality growth assets.

Disclosure: The author holds a position in the stock

I really enjoyed this write-up. Any accumulated cash burn on the mobile side until break-even? High base in e-commerce due to COVID-19?

What do you think of DISH doing the same thing in the US?