Deep Dive: Japanese Trading Companies (Part 2)

Closer look at the business model, management, and capital allocation

Welcome back! This is Part 2 of our deep dive on the Japanese trading companies. Building on the content from Part 1, we explore the business model and the transformation of Shosha in greater detail. We also compare the five major players that Berkshire has invested, giving particular attention to evaluating management quality and capital allocation.

In Part 1, we introduced two major business activities of Shosha: trading and investing. Let’s start by revisiting these, with an emphasis on understanding the competitive advantages that they have in each.

Trading

In Part 1, we discussed the “Shosha winter” period of the 1980’s, where disintermediation was one of the troubles to hit the trading companies. Since then, the threat of disintermediation has always been present. But what’s also true is that disintermediation has played out over four decades, having largely run its course, leaving the trading companies today with entrenched businesses that have generally proved to be stickier and harder to disintermediate. One such business is resources and energy, which we examine below.

Trading companies utilize a mixture of midstream assets that they own in-house or contract from third-party. These include storage and blending facilities, terminals, ships and barges, trucks and rail freight, and light processing facilities. Demand patterns for commodities can be uneven, especially for metals, requiring trading companies to respond dynamically to customer demand. While holding inventory, commodity price fluctuates which means market risks have to be managed or hedged. Trading firms also have operations to blend oil and minerals from different sources in order to meet the quality requirements of each individual customer. All of this is to say that the operational complexity and capital requirements of moving certain goods can be fairly high.

The global commodities trading industry is quite fragmented, with the largest global players listed on the chart above. Relative to these global players, where the Shoshas are really strong is in their relationship with the Japanese buyers. They move large volumes in Japan, and are able to provide better service to Japanese buyers with assets and supply chain that are optimized to serving a single geography. For example, they are highly flexible and responsive to meet the very precise delivery schedules of Japanese manufacturers. Another advantage of Shoshas is their access to low-cost borrowings through strong relationships with their Keiretsu banks. This is often passed down to customers in the form of favorable credit terms - extended payment terms or lower rates than what the customers could obtain on their own. Shoshas also cross-sell more products and services with their Japanese clients, and tend to have wide dealings. For all these reasons they have a very solid business foundation in Japan that outsiders have had a hard time breaking into.

More importantly Shoshas own joint venture interests in mines and oil/gasfields around the world, and thus cannot be disintermediated because they own the actual supply. And with China dominating the global demand picture across most commodities, Japanese demand is increasingly seen as a valuable hedge for many of its partners - especially commodity-producing Western nations like Australia. On this point, it’s also worth noting that Shoshas have the backings of the Japanese government, and will continue to have a seat at the most important resources and energy projects of its allies and partners around the world.

Another reason that Shoshas can’t be disintermediated easily is because they deal with lots of SMEs and not just big customers. Due to capital constraints smaller customers don’t have the resources to build out their own direct sale network, and will continue to rely on the trading companies for distribution. Finally, Shoshas have businesses where they add value through their project management functions and organizational capability of bringing together many suppliers, which makes them harder to disintermediate. An example of this is urban development. But enough on this topic - what’s interesting about Shoshas today isn’t their trading operations. Much more important is their capital allocation, and this brings us to the next area: investing.

Investing

How are Shosha’s investment operations structured? What is their “edge”, if any, as an investment organization? And how are they different from other investment organizations (like private equity)?

Shoshas are organized bottom-up, with each business group responsible for their own investment decisions and P&L. As reference, the organizational structure of Mitsubishi is shown below (see Business Groups on the right). These business groups essentially operate like companies within a company. At a Shosha, C-level executives are typically not involved in investment selection, with the exception of major deals. Because each business group operates largely autonomously, the CFO or COO usually acts like the Chief Investment Officer, ensuring risk management is achieved across the different business groups.

Shoshas’ investing is unique in two ways:

1.) Operating capacity

Compared to a typical private equity firm, Shoshas have the capacity to be more operationally involved. The top Shoshas hire 100-200 generalists each year. They have an army of staff who are ready to be seconded to all corners of the world at portfolio companies. In fact, this act of being “thrown in” is almost a ritual, or expected out of mid-level employees as a way to prove their worth before advancing to more senior management positions.

The goal is not to necessarily take over the day-to-day management of the companies, but to explore avenues of synergy leveraging Shosha’s network (e.g. cultivating new sales channel or new supplier base, or to execute so-called “value chain investing” which we discuss next). The other function is to provide on-the-ground updates to the headquarter. It is often said that Shoshas have a good pulse of their investees and that information gathering is one of their strengths.

2.) Value chain investing

In some investments you will see Shoshas attempt to consolidate an entire value chain. This is an investment strategy that Shoshas considers their own. Itochu’s investment in Family Mart is considered a prototypical example, so let’s understand what this is all about.

Some background information. Japan’s convenience store (CVS) industry has three main players - Seven Eleven, Family Mart, and Lawson. What’s always been the case is Seven Eleven’s consistent market dominance, whereas Family Mart has been the industry loser. Itochu has been working to turn around the fortunes of Family Mart, and the value chain investing lies at the heart of its strategy.

It is sometimes said that CVS in most other parts of the world is a real estate business, whereas in Japan, it’s a supply chain business. Due to large amounts of perishable items sold like bento boxes, stores gets re-stocked three times a day with cold-chain logistics. The demand pattern varies considerably during different hours of the day (reaching peaks during the morning and lunch rush), making on-time restocking of items crucial. But the real crazy fact is this: In a typical 100m² store, a Japanese CVS stocks up to 3,000 SKUs, 70% of which turns over in just a year (sometimes they would develop a new in-house product which sells for one month only!). These are unthinkable in other parts of the world. In other markets, CVS rely overwhelmingly on the convenience factor (e.g. gas stations in the US) and long shelf life items that don’t change. But in Japan, having good real estate alone is not enough. If you don’t provide differentiation through exciting new products all the time, then customers don’t come. That’s how sophisticated consumer tastes have evolved.

Where the value chain investing comes in is that speed and coordination across the supply chain is an advantage in such a fast-moving and competitive industry. By having greater control over the supply chain, Itochu can spin the new product development cycle faster. For example, new products can be developed at a very short notice, informed by analysis of sales trends that might indicate certain tastes or products have become suddenly popular (e.g. cold noodles during an unexpectedly hot summer month). Itochu also claims it has reduced food wastage by 10-30% through better information sharing across the value chain. Itochu Techno-Solutions, the group IT services provider, is in charge of developing a common IT platform for all the affiliated companies.

The potential drawback of this model is capital efficiency. Trading companies will argue that their value chain strategy increases the sum of the parts, but one has to wonder - to sell a ham sandwich for instance, is it really necessary to own the entire value chain down to the hog farms, and even the manufacturing of animal feeds? After all, didn’t Keiretsu lose competitiveness as a result of conglomeratizing too far and having become too insular in the past? Is the value chain investing simply Shoshas reverting back to their old ways?

Perhaps it’s possible to make the case for this style of investing in certain industries, as long as it’s done so selectively. For example one may argue that CVS might get a pass. When done indiscriminately however, it simply becomes empire building. And this is where Shoshas are different today compared to the past - they are picking their battles more and seem to be pursuing the right balance. Where they feel like they have an edge, they are doubling down, and where they don’t Shoshas have been actively divesting their assets. And this is what matters.

The real transformation: Shareholder focus

In Part 1, we’ve already discussed the transformation in their organizational focus from trading to investing. As Shoshas evolved to become more like “real” capital allocators, two trends became visible:

Shoshas began to take larger stakes in companies, concentrating their bets on more high conviction ideas rather than just taking on a large number of minority stakes.

They are also investing more in services industries such as retail and healthcare. Investing is no longer done for the purpose of only securing distribution rights for physical goods.

These are important, but what’s even more important for investors is the internal transformation which had occurred deep inside these firms. To map out the transformation, it looks something like this:

Obsession over chasing topline growth (before 2000)

Shift to focusing on profit (after 2000); and

Focus on shareholder value creation, including capital efficiency and other corporate governance global standards (from 2016)

Once upon a time Shoshas were obsessed over chasing topline, and nobody cared about profit, not even the senior management. Every quarter-end, it was topline growth that motivated everyone from the CEO down to the most junior employee. Former Shosha employee Takayuki Kobayashi recounted in his memoir that during the heydays, there was a Shosha that supposedly did some relatively simple consulting work for a retail chain client, then subsequently recorded all its customer’s retail sales as its own. It was a crazy time - you can say the Shosha equivalent of the dot com bubble, perhaps. As you can guess, this didn’t turn out to be sustainable.

During this time Shoshas weren’t making much profit from their core business of trading, but rather, profit came from speculative real estate and venture investments riding on Japan’s bubble economy. With the bursting of Japan’s bubble in the early 1990’s all of this came to an end. The Keiretsu system also began to weaken. The writing was on the wall that either Shoshas needed to be run like proper businesses, or else they were going to be gone. Some went out of business during this time, and those that did survive had a lot of soul searching to do.

The late 1990’s and early 2000’s was when major changes in organizational structure and management took place. Business groups were given more autonomy, but in return they would be held more accountable for generating profit (the current “companies within a company” structure was borne out of this period). Big change happened with management incentives. In the past, most Japanese CEOs made just a base salary, with virtually zero variable pay linked to financial performance and stock compensation. Shoshas were among the early movers in Japan to introduce compensation best practices.

When you look at how Shosha CEOs and senior officers are compensated, the variable portion has increased significantly. Now, Shosha CEOs make as much as 80% of their total comp from variable (tied to net income growth, and for some firms also cash flow). Notably, the portion tied to achieving topline growth is now zero. Shosha CEOs also own more stocks than before. Itochu’s CEO owns 1.4bn yen in stocks - almost three times his annual after-tax compensation. This may not seem very high still by Western standards and perhaps has room to increase some more. Over the years Shosha incentives have improved significantly to align management interests with shareholders.

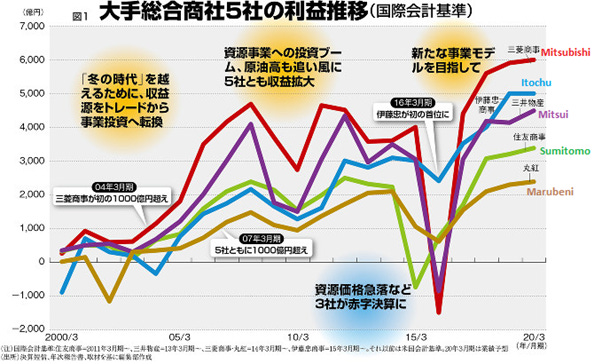

So what came out of these organizational reforms? The chart below shows the profit of the five major Shoshas from 2000 to 2020 (vertical axis in yen, hundred millions). In the early 2000’s, Shoshas collectively made zero profit. Last year, they made $30 billion combined. It’s astounding how much things have turned around.

This brings us to the next question: where are Shoshas now in their transformation journey?

The business portfolios of most Shoshas are still bloated today (legacy of overexpansion under Keiretsu). They are now increasingly focused on capital efficiency - in line with the key objective of Japan’s corporate governance reform - laying out plans to exit underperforming businesses.

“Our problem is that we’ve overinvested in the past. Within Mitsubishi Corp there are around 800 subsidiaries. There are companies in here that we need to re-think their place in the business portfolio. In order to improve our capital efficiency, we need to be divesting some of them”.

- CEO of Mitsubishi Corp

Mitsubishi provides a quantitative target for divestments (1.5 trillion yen in 3 years). This is a marked difference from the past, when they spoke only of making new investments and never about exiting businesses.

Capital efficiency metrics are also making their way into management compensation. At Mitsui, ROE is one of the KPIs used for determining the variable portion of management compensation. But the most impressive is Mitsubishi, where management’s variable comp actually goes to zero if the company fails to generate its cost of capital. More on this later.

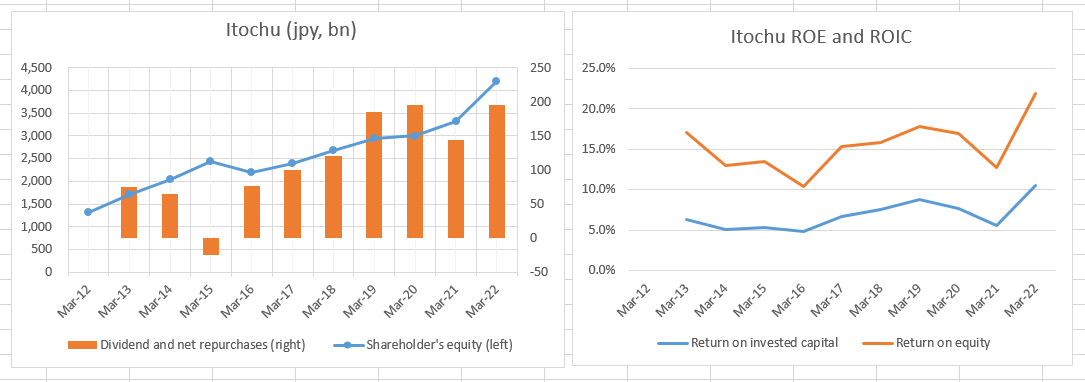

Itochu, which has been the forerunner among its peers to truly embrace this turn to shareholder value creation, has done amazingly well for its shareholders. This provides a blueprint of what is possible for the other Shoshas. Over the last ten years, Itochu grew shareholder’s equity more than three-fold while net returning close to $10bn of profit to shareholders through dividends and buybacks (combined that’s a 10-year CAGR of ~15%). During the ten years, Itochu’s ROIC improved from 5% to over 10%, and ROE from 10-15% range to over 20%.

Shown below is Itochu’s consistently higher ROE relative to the average of four other trading companies

What’s encouraging is that in Japan, every other Shosha is looking up to Itochu as a role model. There seems to be universal respect for what Itochu has accomplished, and this is an encouraging sign. Improvements at Shoshas have come a long way, and they will continue to get better. After all, is it reasonable to assume that these organizations, with their ability to attract the country’s best intellectual capital, would perpetually under-earn their cost of capital even as they reset their priority to focus on shareholder value creation?

Comparing the five major Shoshas

From an investor’s point of view, the major differences in the five Shoshas comes from two things: 1) business portfolio (particularly the contribution of resources/energy in the mix); and 2) management quality.

Business portfolio

As you can see above, the exposure to resources/energy at each firm can differ by quite a lot. Of all the Shoshas, Itochu is best known for its strategy to shift away from resources from early on, and is one reason for its premium valuation over others. Not surprisingly, the companies with the largest exposure (Mitsui and Mitsubishi) also tends to have the highest earnings volatility too.

Below shows the top five businesses at each Shosha:

Resources are still the largest business at all the Shoshas. Excluding this, the rest tends to be quite long-tail. There is not a single business that will make or break a company. If a single subsidiary contributes to 5-10% of a Shosha’s bottom line, then that’s considered really big.

Although each Shosha is highly diversified, there are industries where each firm places greater strategic focus than others, i.e. there is specialization to some degree. Itochu is more focused on services and consumers. Mitsui and Mitsubishi are known for their very high commodities exposure, but they’ve also been historically big in the automotive space. Mitsui has the Penske stake/partnership in North America, while Mitsubishi has significant distribution interests in Southeast Asia for commercial trucks and pickups (subsidiary Tri Petch Isuzu has monopoly over all sales of Isuzu trucks and aftermarket parts in Thailand). Sumitomo has been more focused on media and digital transformation through its ownership of JCOM (Japan’s largest cable TV) and SCSK (system integrator). Marubeni is overweight agriculture through its US subsidiaries Gavilon and Helena.

Management, capital allocation, and governance

Trading companies span a cross-section of good to bad management. I would place them in the following tiers:

Tier 1: Itochu

Tier 2: Mitsubishi/Mitsui

Tier 3: Marubeni/Sumitomo

The below chart shows the cumulative extraordinary losses (impairments) at Shoshas from 2010 to 2022. Notice the difference between the first and last place. Marubeni and Sumitomo have impaired 39% and 30% respectively of their equity base over the years, which is truly extraordinary.

The gap between the first and last place is huge, and you can easily tell by listening to the CEOs of these companies. Itochu’s CEO emphasizes often the importance of profitability and cash flows - just like what one would expect to hear from any CEO focused on shareholder value. He doesn’t believe in making large directional bets or moonshots, and instead, prefers steady returns in boring but predictable industries. Marubeni’s CEO, on the other hand, like to talk about the firm’s social and environmental contributions at every given opportunity, and has even been caught saying in an interview that “perhaps one day the goal of a company isn’t to make profits anymore”.

“When it comes to DX (digital transformation), there is a tendency to pour as much money as possible into them. Everyone is saying they’re investing for the future, but do they have much results to show for? Take connected cars and autonomous vehicles as an example - I can understand why Toyota and Honda invests in them. But what kind of value can a trading company add in that field? These kinds of speculative things we just let other trading companies do them first. And then we will be watching them carefully.”

– Okafuji Masahiro, Chairman/CEO of Itochu

A good demonstration of the above philosophy is the fact that Itochu has invested the least in renewables out of all of its peers. Itochu tends to resist jumping on popular trends, and will not rush out to do something until industry returns become more established.

Itochu is also most willing to exit underperforming investments - Itochu had over 300 loss-making subsidiaries in 2000, but this is now fewer than 50. In 2021, the number of subsidiaries at Itochu at or above profit breakeven reached 90% of total. For Mitsubishi, this is 74%. As far as I know these two are the only two that are disclosing and tracking this metric with investors. One way to think about it is that Mitsubishi has more room for portfolio rationalization, so the upside potential may be greater from here.

Culturally, there’s also quite a lot of difference between the five companies. According to sources, Itochu is the most entrepreneurial and are known for having the most ambitious employees and the hardest working culture. There is an underdog mentality (although no longer an underdog), and some attribute this to them not hailing from a Zaibatsu background (elite clubs like Mitsubishi and Mitsui). Itochu is also a close-knit organization, and culture that is almost cult-like with strong influence of Chairman/CEO Okafuji’s leadership and philosophy. The following slide, taken from Itochu’s investor presentation, talks about “overpaying for investments” in the past. It’s a refreshing statement - how many public companies will admit to such? Perhaps it speaks to an introspective and intellectually honest culture at Itochu.

Mitsubishi and Mitsui are elite organizations with strong talent as well, but organizationally they are more steeped in their history and roots. They can be more bureaucratic and slower moving. On the other end of the culture spectrum is Sumitomo which, according to some sources, has the weakest or least distinct culture of all. Some have even described it as having a quasi-government style work culture where employees tends to get better hours and holidays than the other firms. Marubeni is probably somewhere in between.

Now let’s look at how management is incentivized. Japanese executive compensation is often criticized for being un-incentivizing, but from a shareholder’s point of view I believe Shoshas have some of the most reasonable compensation structure in the world. Here’s a summary:

Observations:

You can see that all the Shoshas pay a substantial portion (60-80%) of total comp as variable which is tied to the firm’s financial performance. Net income is the main one that it’s tied to, but some firms also include a cash flow component too (50% net income and 50% cash flow). None are tied to achieving topline growth.

The most impressive one is Mitsubishi. Variable comp goes to zero if the company’s net income comes in below its “cost of capital”, which the firm has calculated as 520bn yen for fiscal year ending March 2022 (Note: the actual net income that year was 937bn). We can easily deduce the WACC as 4.4%, and assuming cost of debt at 1.1% and with effective corporate tax rate of 30%, we can back out the implied cost of equity as 7.6%. This looks fair (not a low-ball attempt). The fact that Mitsubishi has incorporated capital efficiency into its compensation structure in such a major way is highly positive. From this alone, you can tell how far governance has come.

As for Itochu, I think they could use some improvement in the compensation structure which is currently overly fixated on just net income growth. For example, they should incorporate a capital efficiency component. Though it is good that Itochu’s CEO (and board) has greater equity ownership than other Shoshas.

Overall, the absolute level of executive comp is reasonable and not excessive (excessive comp has never been a problem in Japan anyways)

To summarize, Itochu is closest to being what an investor would consider a rational, shareholder value maximizing organization. Mitsui/Mitsubishi are also interesting as they trade on lower valuation, while having more runway for portfolio improvement, with management teams that are conscious of good governance and committed to closing that gap. As for Marubeni and Sumitomo, they have the longest way to go and I don’t deny the potential for positive outcomes to emerge, but the gap with others is still quite big. I want to believe in them but need to see more.

What are the risks?

I don’t see a ton of risks buying these companies at their current valuations - especially given any substantial decline in their share price is likely going to trigger more buying from Berkshire. However, the following risks are worth noting:

Resources/energy exposure (especially for Mitsubishi and Mitsui). This is mostly a cyclicality issue, but perhaps there is some structural risks here to consider too. Shoshas have largely divested from thermal coal, but they still have large exposures to iron ore and coking coal. There will always be long-term concerns in technology, like the shift to hydrogen reduction steelmaking (doesn’t use coking coal) or growth in electric furnace (utilizing scrap steel) leading to reduced iron ore demand. It’s also worth monitoring how these firms plan to grow their share of portfolio in the high value “de-carbonization” metals (where demand is rapidly growing but a highly competitive space).

Interest rates - all the Shoshas are indebted and historically benefitted from the ultra-low interest rate environment in Japan. Rising interest rates will put pressure on this model. For example, Mitsubishi has total interest-bearing liabilities of 5,643 billion yen, paying on average interest rate of 1.1% (most are floating rate). If interest rate doubles, then this will hit bottom line by about 60bn yen.

Shoshas are people-based businesses and culture plays a big role. More successful players like Itochu have to manage itself against the insidious risks that comes with success, including complacency, overconfidence, and failure of risk management, which tends to be the things that bring down prominent investment organizations. So far, I don’t get the sense that this is a problem right now.

For those that are seeking a Japan allocation in their portfolios, we believe trading companies are worthy of considering. The alternative to actively picking stocks in Japan is just to buy and hold these trading companies, much like how someone in the US market might invest in Berkshire to get a broad exposure rather than picking individual stocks. From the point of view that Shoshas provide good inflation protection, continues to improve in terms of management and governance, while trading at statistically cheap valuation makes for a compelling case. And perhaps these are what Warren Buffett saw.

Nice Job!

On your research did you read about Glencore aquisition of Gavilon?

Do you think Marubeni wants to reduce exposal to agriculture, or any other reason?

Hi, I am wondering for Mitsubishi how did you reach the conclusion for their WACC, cost of equity, etc.?