Summary:

Grab is Southeast Asia’s dominant on-demand platform for ride-hailing and deliveries. It is also one of the top mobile wallet/fintech player in the region.

Amidst the dramatic turn in macro and capital markets conditions, incentives spending in the industry seems to be coming down fast and across the board as management teams’ focus shifts to profitability. While share prices of tech companies have been severely punished, the downturn may also be a positive turning point to catalyze more rational industry behavior moving forward.

Grab is a net beneficiary of Southeast Asia’s brisk pandemic recovery as business and tourism travel normalizes (bookings and driver supply currently at ~70% of pre-pandemic levels).

Stock price is down ~80% since listing, yet we only think this is approaching fair value (which goes to show the extent of the bubble! But we’ll let you decide)

The past decade

The past decade for the on-demand economy has been a rocket ship. In 2014, Bill Gurley famously claimed $6 trillion TAM for ride-hailing, which quickly swept across the world over from New York to Singapore to Jakarta. On-demand food delivery also came into the scene, and the gig-economy was in full swing. Uber became the most valuable private company in the world, and at one point sought IPO at $100-120 billion, all while still generating losses.

“It was purely a volume business…How many orders, how much GMV can I generate? Irrespective of all of the cost. It was really that high growth rocket ship dynamic…”

– Former Head of Growth, GrabFood Indonesia (Stream by AlphaSense)

As long as the music kept going, everyone was happy. But with the drastic change in capital market conditions since late last year, the music stopped and the game changed. No longer can these businesses rely on an infinite supply of money at higher and higher valuations to fuel their growths. There is no sugarcoating the fact that much of the past had been a growth experiment enabled by the monetary conditions of the time.

Ever since the cycle turned, Grab’s share price has fallen like a rock (down 80% from IPO). We went into the carnage to take a look at Grab with a fresh set of eyes: what next for this business, and is there an investment case to be made?

We assume most of our readers are generally familiar with the Grab story. But if not, here’s a very condensed version: The company was founded by Anthony Tan and Tan Hooi Ling as MyTeksi in Malaysia in 2012. It started as an app for calling taxis, but later added its own driver-partners for ride-hailing, and also expanded into food delivery and payments/financials. Since 2013, Grab started to expand rapidly into other markets including Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Philippines. At around the same time Uber expanded into the region and became Grab’s main competitor until 2018. Dara Khosrowshashi, Uber’s new CEO, saw that the writing was on the wall and sold its Southeast Asian operations to Grab. At the time of sale Uber obtained a 27.5% stake in Grab (which is now 14%).

The bull case: a turning point

While the macro environment has turned into a more unforgiving one for loss-making tech firms, bulls would see today’s environment as being a positive turning point for the whole industry, and particularly so for incumbent leaders like Grab. If competitors and new entrants weren’t able to dethrone Grab in an era of easy money, it is less likely than ever that anybody is going to do so now. At the same time, the industry is beginning to show signs of rationalization as focus shifts to profitability, away from the past cycle norm of chasing growth at all costs. Having emerged victorious coming out of years of destructive competition, can Grab finally start to reap the fruits?

The Southeast Asian “homegrown” players, notably Grab and local Indonesian competitor Gojek (Gojek Tokopedia, or GoTo, after their merger in May 2021), have built their businesses around a dominant "super-app" strategy, which incorporates ride-hailing, deliveries, payments, and other consumer services.

“With features like cross-vertical batching, a driver partner can pick up someone’s kid, send him to school, after the school pick up food, coffee, do the grocery run (delivery)…the beauty is that the driver has the super-app on his/her side, he/she is working at very high throughout, very little dead time, where we don’t have to pay for incentives for that time”

- Anthony Tan

As the industry is forced to move away from the past model of excessive subsidies, the staying power of the super-app model may become more apparent given the advantages it has in user retention/acquisition (e.g. sending ride-hailing users to food delivery) and driver utilization. Particularly it remains to be seen how well pureplay platforms like Delivery Hero (Food Panda, the second largest deliveries player in the region) is able to fend off against Grab in the new landscape as promotional spending which they so heavily relied on will be tapered.

“Growing is not that hard as long as you raise a lot of venture money. Growing profitably and ultimately reaching a sustainable equilibrium in terms of unit economics in the long-term, that’s a lot harder. I would think Grab Food and Gojek are probably the only ones that really have a shot at that”

– Uber former Chief of Staff, APAC (Stream by AlphaSense)

The key for any commoditized industry to generate excess returns is consolidation, which is necessary to attain pricing power and the scale/density for lowering cost. In ride-hailing, Grab enjoys monopolistic positions across all major Southeast Asian markets (70-90% market share), with the sole exception of Indonesia where it splits the market roughly evenly with local competitor Gojek.

Food delivery is generally a duopoly-ish market (top two players average 88% of the market in the six key markets). But usually a small third or fourth player also exists, with opportunities for further consolidation. In particular we think ShopeeFood needs to rethink its strategy of spreading bets across the region, as it remains a distant small player (with the exception of Vietnam). Its rights to win remains unclear. ShopeeFood’s synergy with Shopee’s core e-commerce operations also seems questionable. Recently, Sea Group announced a new round of layoffs which included cuts to ShopeeFood. We’ve seen Sea pull out of many of its international markets recently. Maybe next step is rightsizing the food deliveries operations.

Notably for the first time, all major players operating in the region are now publicly listed firms (Grab and GoTo have gone public in the last six months, plus Delivery Hero and Sea Group which are listed). Facing languishing stock prices and pressure to land on a sustainable business model, managements are now strongly emphasizing profitability as the core focus. For example, in Grab’s Q1 earnings call, keywords “cost efficiency” and “cost discipline” were mentioned 12 separate times.

The industry is undergoing behavioral shift, which we have already begun to see:

“In terms of incentives we’re seeing competitors overall are tapering on incentives…market is rationalizing and also being more constructive at the same time”.

– Grab management Q1 earnings call

Confirming this, Grab’s incentives paid (total of partners and consumer incentives) declined sequentially in Q1. Even as incentives were tapered, GMV continued to rise which is encouraging to see. The same sequential drop in incentives is also observed at GoTo’s Q1 results.

“I think it’s fair to say peak competitive intensity has passed. There’s significant margin pressure with investors demanding these firms to demonstrate a viable path to profitability and what we’re seeing in food delivery and also aggregator/platform type businesses is cuts in marketing budget and higher delivery fees to try and solve for improved margins.”

– Food delivery industry contact (private)

And this trend is not just for food delivery - we are seeing incentives spend being reigned in across the board:

“We are at a market condition where cashback is no longer the main reason why users would choose which digital wallet they want to use. Because the incentives are now decreasing...starting in 2021 and until this year, in 2022, all of these wallets: GoPay, OVO, ShopeePay, are in the same level where they no longer burn a lot of cashback to the market.”

- ShopeePay, SeaMoney Campaign Marketing Lead (Stream by AlphaSense)

So the level of promotional spend is definitely coming down. Where the spend will eventually level off, and how fast the services can continue to grow even in the face of spend cutbacks are things that investors will be watching closely.

A common but misplaced criticism is that these on-demand businesses have never been profitable, and that their economics simply don’t work. Even in the food delivery business (which has lower profitability than ride-hailing), it has already been demonstrated that the business can get to decent levels of profitability in certain regions. Across the world, in affluent cities operating under a single/duopoly market structure, food delivery has achieved 5-8% adjusted EBITDA margins (as % of GMV). The model works economically as a hyperlocal business in selective regions, and it’s only when these companies over-extend and try to spread across entire continents that they run into real trouble with profitability.

Usually there is a huge skew, with the least profitable regions contributing disproportionately to lowering the overall profitability for the companies. Uber discloses this which you can see below, and this kind of spread is pretty much the same across all major players. Uber already has 10 markets where delivery is adjusted EBITDA positive, and five of them have above 5% (as percentage of gross bookings).

There could be significant “opex put” in these businesses, due to meaningful improvements that can be had by culling the small number of regions that drag down profitability disproportionately. At this point, it needs to be recognized that some degree of demand destruction is necessary and healthy for the industry, although this needs to be tempered with management’s actual willingness to reset and undo parts of their past empire building efforts.

What the bears say

Bears would push back in several ways.

They argue that these businesses have created consumer value propositions and thrived only due to their heavily subsidized models. Is being chauffeured around in a private car or having meals delivered on-demand supposed to be affordable in the first place? You can create your own category and achieve high shares which may sound impressive, but category leadership means little when there is high demand elasticity and availability of substitutes (e.g. ride hailing vs. taxi, delivery vs. picking up food). Demand destruction would eat significantly into TAM and growth, should the industry try to raise prices (or reduce incentives spend) to make the economics work.

Bears would argue that costs are understated, and that this is hardly a scalable business that it makes out to be. Grab’s driver-partners are supposed to be independent contractors that are responsible for their own P&Ls. But it is not only the users who are fickle in this business, but also the drivers too. As a thought experiment, what happens if oil prices double? Unless it can perfectly pass this burden on to riders (not likely), Grab most likely would reach into its own pocket to protect driver earnings to maintain supply. In addition, regulatory rulings to enhance driver welfare could lead to higher costs by entitling drivers to additional benefits such as holiday pay, pension benefits, and healthcare. All of this means that instead of looking at the business as an intermediary platform, perhaps it should be treated as if all of the productive components (drivers, vehicles) are actually part of the company and not separate from it.

All big tech firms suffers from regulatory risk. But there is still a difference between the usual suspects that just focus on the digital realm like ads, versus one that employs hundreds of thousands of working class people to disrupt verticals like transport and food. Regulators are not just concerned about driver welfare, but also on the consumer pricing side as well. For example, recent surge in fares have prompted the Malaysian Transport ministry to ask ride-hailing companies to explain and clarify the fare increases. While fares are determined by algorithmic adjustment based on demand & supply, it still political contentious. Is it appropriate that Grab is allowed to adjust fares in real time, while taxis drivers are not?

What about Grab’s management? An ex-Grab employee has stated on his blog

“My time at Grab left me thinking very highly of Anthony Tan. He has a unique ability to be able to motivate the troops though a healthy balance of vision, passion, and old-fashioned pushing. On several occasions, I observed him come into meetings and convince the group that something they deemed impossible was indeed possible, or at the very least to give it a try. Further, his ability to raise money was unreal, and frankly, this was the ultimate weapon in winning the war against Uber.”

It seems like a fair description as Anthony Tan seems very charismatic, and his skills in raising money, instilling vision, and pushing people were crucial for helping Grab win the war of market share of the past decade. But what about now that the rules of the game have changed? It’s less about selling vision, but more about operations. And it’s less about chasing growth at all costs and more about the bottom line. As we enter an uncharted territory for the company, can we still anchor to the past narrative of a strong founder-led management? Time will tell.

Of course, there’s also the argument that culture is enormously hard to change. As told by an ex-Uber employee, “A lot of these people who want to be chief product officers want to be able to do something where they can grow and do something so unique.” It remains to be seen what a cost-cutting environment would do to the talent pool and culture at these companies.

Lastly, although still a longshot, self-driving (robotaxi) is something to ponder when thinking about the terminal value of this business. We have no insight on when this technology will arrive (probably not for a very long time but who knows). But this is something that could render the current two-sided platform model obsolete. Whichever player has the most cash to acquire the largest fleet of autonomous vehicles, and has technology to operate them likely wins. Rather than any of the current ride-hailing majors, note that the companies leading in the autonomous race so far are players like Waymo (Alphabet) and Baidu.

Mobility segment (ride-hailing)

The financial statement of the mobility segment is shown above (note: excess incentives just means how much is paid to the driver beyond the commissions that Grab has earned from that driver). The caveat is that Grab has a ton of corporate costs and SBC that’s not being reflected in the segmental adjusted EBITDA, and thus this metric is obviously flawed as a measure of the company’s real profitability. However, it does serve a purpose for approximating the contribution margin of the mobility business.

You can see that for every $1 of fare, Grab earns about 10-12 cents, net of all incentives paid and other COGS including driver insurance. Even at the depth of Covid shock in 2Q20, when GMV plunged by more than 70%, segment profit remained positive. The level of incentives spend at mobility is about 40% of gross revenues, versus 80% for delivery, which is the result of a more consolidated industry and lower competitive intensity in ride-hailing.

There is a saying that the ride-hailing business is one where you can capture but not generate consumer demand. Companies don’t have too much influence on how much people travel (this is unlike food delivery where it’s more possible to influence order size through various ways). Ride-hailing GMV is highly influenced by the level of overall travel in the economy. Obviously, Covid has destroyed this business in 2020-2021. Now, most Southeast Asian countries are recovering from Omicron. Every country in the region is now accepting tourists, and business travel has also bounced back. Sustained re-opening will be a tailwind for the rest of the year and into 2023.

What we see (not just in Southeast Asia but globally) is that Covid has also led to a semi-permanent departure in the supply of drivers. Frustrated, some drivers decided to take an indefinite break from driving, while others left big cities during the pandemic and went back to their hometowns to live with family. Now as travel is resuming, Grab needs to “reactivate” these dormant drivers. If left to market forces, drivers will perhaps come back to the market eventually at some point, but the process will be slow. Meanwhile supply shortage would end up hurting user experience as fares surge and wait times grow, which is why Grab is spending now on driver incentives to give supply a further push.

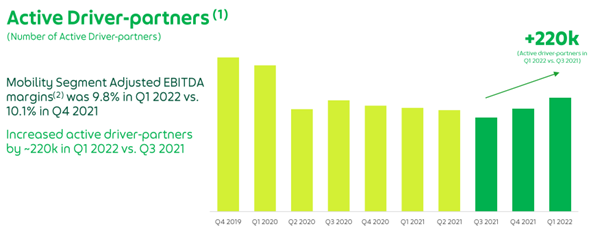

As shown below, after bottoming in 3Q21, driver supply is on its way back, although in mid-May the number of driver was still at less than 70% of what it was pre-pandemic. But encouragingly, what we’re seeing is that despite the higher fares and longer wait times in some cities, demand for ride-hailing remains strong overall. This goes against the notion of demand being totally elastic in this business, and we can talk about all the reasons why this might be so (better user experience). Exiting the first quarter, mobility GMV grew 32% from March to April, and Grab management expressed strong confidence for the continued ramp in demand.

“Overly optimistic for the next few quarters (in mobility)”

- Anthony Tan

We recently spoke to a driver in Singapore who commented that net of Grab’s 20% take rate, he currently earns $400 SGD, and after paying for gasoline and rental fee for the car, his take home pay is $280. This is working 10 hours a day and doing two trips per hour (an undemanding schedule for a full-time driver). The pool of supply for gig workers grows from layoffs caused by the tough conditions in the economy, and this is something that we are also beginning to see. We foresee no issues in the continued ramp up of driver supply.

“We’ve seen driver earnings improve qoq, yoy, utilization has improved, as our incentives as proportion of GMV comes down”

- Anthony Tan

Another thing that really helps to support driver earnings is airport trips (which evaporated during to Covid). In Q1 airport trips accounted for only 6% of total fares at Grab, which could go back to the teens percentage eventually (for Uber it was 15% pre-Covid).

The bottom line is that the recent increase in incentives spend for ride-hailing is not indicative of a structural deterioration in economics. It’s fair that investors treat the increase as one-off that’s necessary to get driver supply back to normal levels. Management expects to be able to taper off on the incentives in the latter half of the year, and once normalized, the business should deliver even better economics.

Deliveries segment

While deliveries GMV growth has been very strong, profitability has been the challenge here historically. High levels of consumer incentives is the main reason. Another reason is order quality, as high volume/small basket sizes drive the mix. Popular fast food outlets and large chains can be popular and generate a lot of volume, but they aren’t profitable. According to an industry contact, due to their bargaining power large chains get very low commissions (5-10% or even lower), compared to independents that foot a much higher bill at 25-30%. While big chains can bring on users and build usage, it’s necessary for platforms to lean into independents in order to monetize.

To improve profitability, platforms can raise minimum order sizes, menu prices, and/or delivery fees. This accomplishes two things. First, it raises margins of existing orders. And second, it leads to demand destruction from the shedding of unprofitable (low quality) orders. Consider that when you raise delivery fee from $1 to $2, the user who is ordering $6 of fast food is likely to be discouraged from ordering, much more so than the user ordering $50 from a steakhouse.

“The bigger benefit on margins is not increasing margins per order but actually shedding unprofitable orders. So the true uplift on margins for a 10c fee raise can be a 13c contribution depending on consumer dynamics”

– Food delivery industry contact (private)

You can imagine that if Grab raises its delivery fee, and if its competitor does not, what ends up happening is that some of the most price-sensitive (lowest quality) users would switch over, which worsens the mix and profitability for the competitor. When the industry’s focus used to be volume and market share, the competitor may have happily taken on this additional volume. But when all the players in the industry today have promised their investors with margin targets, they are incentivized to follow up with price increase of their own, which is how the industry should be able to push through with higher pricing this time.

Can consumers absorb the price hike? There seems to be room for higher delivery fees to be supported given the current low base for fees in the region. Even with higher fee, there should be a core group of users that see high value in the service that continue to use it.

“Post-pandemic aggregate food delivery demand is going to drop but there will be a segment of consumers who will continue to order. On average, these consumers are generally higher quality and have the ability to pay – targeted price discrimination feels relatively unexplored”

– Food delivery industry contact (private)

Typically these are urban young professionals who are willing to trade money for more leisure or productive time. We see this relatively sticky cohort of users globally, whether they are in London, Amsterdam, or Jakarta. Affluent urbanites basically behave similarly around the world, and value similar things. For them, while food delivery is a discretionary spending, it is also kind of a must-have. We don’t imagine a world where every single person (and their grandmothers) are getting food delivered, but we do see a group of relatively sticky high-quality user base that will be core to the platforms’ ability to earn.

Beyond this, there are a number of growth optionality in the business that’s worth mentioning, although we will preface it by saying that they are mostly still in very early stages. Our conviction in most of them falls short when thinking about whether they can get to a significant enough scale to meaningfully move the needle.

Advertising: advertising revenue is accounted for in the smaller Enterprises and New Initiatives segment. However, we mention it here since it’s closely tied to food delivery, as restaurants are expected to be the bigger buyer of ads. In Q1 management disclosed that the advertising business grew 7x and saw very effective small merchant ads with “600% ROI” (take this with a grain of salt as we don’t know what this means). Uber is also bullish with its ad business, expecting it to become a $1b+ revenue generator by 2024, which will correspond to about 1-2% of GMV. Delivery Hero has an even higher target for its ads at 3-5% GMV. At scale ads could be a profitable business, but it leaves the question of just how much more additional value can be extracted out of restaurants, which are already paying quite a lot in commissions.

Cloud kitchens: These are delivery-only kitchens that have no dining hall staff to pay for, and rely exclusively on delivery platforms to fulfill all their storefront functions. The appeal is that platforms could therefore charge a higher commission than regular restaurants.

Membership: In some regions like the US, memberships have become a big part of the delivery business (Dashpass accounts for more than 40% of its gross bookings). However, according to a food delivery industry contact, it’s difficult to design a membership program that is attractive to users while also being profitable for the company. Players like Food Panda and Deliveroo have been reluctant to make a focused effort to grow subscription for this reason. And for Grab which already enjoys the top consumer mind share as the region’s leading app, a membership strategy may not bring much added upside.

Grocery and retail (Grab Mart, Grab Supermarket) – Delivering groceries and non-perishables can significantly expand Grab’s addressable TAM, but this is a lower margin business than food delivery. And given management’s focus on profitability, they have not talked about this business recently as much as they did before.

Acquisitions (Jaya Supermarket) – In January Grab completed its acquisition of Jaya Grocer, a mass-premium supermarket chain in Malaysia with 44 physical stores. It’s estimated that Grab’s Q1 includes roughly two months of Jaya’s results (~$300m in annual revenue). Accounting becomes messy as sales of products are lumped in together with delivery commissions under one segment. Until management does a better job of providing cleaner disclosures, investors will have to adjust this manually.

Enterprises services - Grab seems to be making a bigger push into developing new streams of B2B revenue. Notably it was announced in June that the company has launched GrabMaps to tap into the enterprise mapping service in Southeast Asia - a supposedly $1 billion market opportunity per year. If you are interested, you can read more about it here.

Financial Services segment

This segment includes Grab’s payments business, plus a collection of other financial services including loans, insurance brokerage, and BNPL, which are all in early stages. As shown above, 62% of transactions in this business comes from “on-Grab” (users using GrabPay to pay for rides or delivery). Historically off-Grab growth has been relatively weaker, however, economic re-opening could lead to stronger growth as usage increases in the real economy.

It’s intriguing as to why this segment wasn’t included together with Mobility and Deliveries as part of management’s profitability targets (especially when Financial Services has the lowest segment profit out of all three). It remains to be seen whether this segment can grow into a standalone business that has the potential to become a lucrative profit center on its own. There is an aspect of this business that seems to be used for supporting and subsidizing other businesses at Grab (e.g. loans provided to Grab merchants at rates much lower than market). We wish management can help investors better understand how the business is positioned.

There have also been some business setbacks that Grab’s mobile wallet business OVO has faced in Indonesia over the past year. At one point OVO had the leading market share in Indonesia. Local firm Tokopedia was a co-owner in OVO, and helped to drive significant transaction value through its e-commerce. However, since the merger with rival Gojek (which operates GoPay), Tokopedia has sold its stake to Grab (which now owns ~90% of OVO), leading to market share loss for OVO as Tokopedia users shifted into Gojek’s GoPay.

In other regions, Grab is focused on launching digital banking, with the Grab-Singtel Digibank joint venture set for launch in Singapore in 2022. In addition, its joint venture in GXS bank has recently been granted a digital banking license in Malaysia. Earlier, Grab also acquired 16.3% stake in Bank Fama which will be a launchpad for digital banking business in Indonesia. Grab is working on building a common tech stack for its digital banking businesses in the region, but with differing regulatory requirements across each region, it remains to be seen how fast they are able to scale these new businesses.

Putting it together

Above, we project Grab’s key financials out to 2027. Key assumptions are:

16-20% GMV CAGR across the three business segments.

Flat commissions rates for Mobility and Deliveries, and mid-single digit increase per year in Financial Services due to mix as it focuses on growing and launching new value-add services.

Improving profitability, reaching 14% margin for Mobility (not a longshot as this has already been achieved in 1Q21), 2% margin for Delivery (as per management guidance which we believe is still conservative). Financial Services will narrow losses but still won’t breakeven in 2027.

With cost reduction initiatives, firmwide cash costs grow at 5%.

Under this trajectory of improvement, you can visualize how the cash position changes over time (good news is that balance sheet is strong enough). Note that due to the large amount of initial cash burn, enterprise value increases rapidly at first. With ~$6 billion of net cash on the balance sheet as of end of Q1, at first glance it may seem like the company is being valued at 6-7x 2027 FCF (at share price of $2.50). However, the actual multiple must take into account 1.) cash burn, and 2.) dilution due to SBC (which is not captured in FCF). When these are taken into account, the multiple becomes 13.3x 2027 FCF.

While we believe the company’s turnaround narratives is sound, the rate at which the bottom line actually improves is hard to know, so the trajectory is something that will need to be fine-tuned as we get more clarity over time. But the way you should look at it is that these are somewhat of a minimum set of assumptions on the business improvement that you are going to have to be willing to underwrite, in order to make sense of Grab’s valuations around today’s levels.

Readers may also wonder whether to invest in Uber instead. Uber has a faster path to positive cash flow/profitability, and by several metrics it also looks cheaper relative to Grab, which makes for a compelling alternative. Uber could be the more resilient option in the current market which places higher focus on cash flows. On the other hand, Grab might be justified by a Southeast Asia premium (young and growing population), being one of the few premier tech giants in the region. Compared to Uber, it also enjoys stronger positions in the markets it operates in. For example, DoorDash is by far the most dominant delivery player in the US, but there is no market that Grab operates in which it is not a top player in (or tied for top). There could be more optionality for Grab as well, particularly in fintech.

Ownership and lock-ups

Grab became a listed company on December 2, following its SPAC merger with blank check company Altimeter Growth Corp (led by Altimeter Capital founder/CEO Brad Gerstner). The transaction valued Grab at ~US$40 billion and raised $4.5 billion in cash proceeds.

There are three groups of shareholders of interest, which we will examine in turn.

1. Major shareholders from pre-SPAC

Grab’s largest shareholders are Softbank (ownership: 18%), Uber (14%), Didi (7%), and Toyota (6%). Their lockups expired six months after listing (on May 30, 2022), which means they are now eligible to sell their stakes. Uber and Toyota are believed to be the more stable holders, while Didi and Softbank have been under business pressure and are likely the less predictable ones. Shown above, these early investors are all under water on their average cost of acquisition. This leads us to believe that these holders will not be inclined to sell, unless they are forced.

2. Management

Anthony Tan owns 3.6% of ordinary shares outstanding, although his class B ownership grants him effective control with 62% of voting power. Key Grab executives (Anthony Tan, Hooi Ling Tan, Ming Maa, and others) have signed a new lock-up agreement on March 14, 2022, which will prohibit them from selling until May 30, 2023.

3. SPAC sponsor

Altimeter (Brad Gerstner) has their skin in the game in two ways. First, through SPAC sponsor promote shares (~20% of AGC which is now equivalent to ~0.3% of Grab shares, or ~$29 million at $2.50 per share). This is effectively the “reward” that Altimeter received for doing the work as a sponsor. Sponsor promote shares are under a three year lockup, expiring December 1, 2024.

In addition, Altimeter has committed $750 million (as part of the total $4.0 billion PIPE funding) from funds managed by Altimeter Capital Management. This is the part where Altimeter is really eating its own cooking. If Altimeter is still holding onto the entire position (we are not aware that there is a lock up for this portion), then it is currently sitting on a 75% loss to its cost basis of $10 per share, at a market value of ~$188m. Together with the the sponsor promote shares, Altimeter holds a little over 2% of total shares outstanding.

It’s obvious that Altimeter has top-ticked the market with this one, and Brad Gerstner has been quoted on the air saying that he is “not happy” with the outcome (not surprising!) However, there’s been surprisingly little mention of Grab by Brad and his team since the listing. Brad’s reputation and track record have drawn a lot of people to invest - so Brad, if you happen to be reading this, please share with us your updated thoughts!

PS - The past months have been extremely tough for many investors in tech. There are lots to think about in terms of how investors should consider volatility, conviction (or perils of), diversification, etc. in this environment. If you are interested, we wrote about these in another post here.

If you are looking for an expert network to get up to speed on industries and companies, then we highly recommend Stream by Alphasense.

Stream by Alphasense is an expert interview transcript library that has been integral to our research process. Select quotes we used in this research were sourced from Stream. They are a fast growing expert network with over 15,000 transcripts on a wide variety of industries (TMT, consumers, industrials, real estate and more). We recommend Stream for its high quality transcript library (70% of experts are found exclusively on Stream) and easy-to-use interface. You can sign up for a free trial by clicking here.

Disclosure: The author and his clients have positions in the securities mentioned in this article.

Hey guys! Thanks for all the wonderful writings (the open-RAN point on the Rakuten piece is especially nice touch)! Regarding the food-delivery-ish business (I know grab is not entirely that), curious how you guys think about the unit economics (from restaurants’ ,consumers’ , and couriers’ angles respectively) and if you guys think that the excessive profit for mobility business in the future might just attract potential entrants to strong-arm into the market with huge initial spending on incentives (a good example might be Meituan entering ride-hailing business in China). Also, from SOTP perspective, how shall investors think about assigning multiples to respective business segments. Appreciate if you could provide further insights!