Deep Dive: Dollar Tree (DLTR) - Part 1

Lay of the land: Dollar store industry fundamentals

We want to acknowledge that this idea and content came from a good friend of Value Punks - Conor O'Kelly. Conor is a skilled investor focused on global equities. He was recently a senior analyst at a large institutional manager. Give him a follow here!

Part 1 will cover the essentials - all about the fundamentals of the dollar store business model including industry landscape, value proposition, moat, economics, and growth

Part 2 will delve into the details on DLTR’s management, valuation, risk factors, and tactical considerations when thinking about the stock

THESIS SUMMARY

After falling from >$160/share, Dollar Tree shares offer an attractive entry point at ~$107 for investors willing to invest over a 3+ year time horizon (3-year target price: $200).

The core thesis points are:

Attractive industry: Dollar stores have been steadily taking share in retail for decades; since 2016, public dollar stores have grown revenue at ~8%pa, increasing their share in addressable categories from 3.1% to 3.6%. Share gains will continue at the expense of pharmacies and the long tail of independent retailers. They offer a difficult-to-replicate value proposition that is insulated from e-commerce competition, evidenced by average long-term returns on tangible capital of >20% and new store expansion rate of >1k per year despite the ongoing “retail apocalypse” (>50% of all new retail units).

Self-help opportunities offer (material) idiosyncratic upside: Both the Dollar Tree and Family Dollar banners have material opportunities to improve sales productivity and operating efficiency. After initiating several projects just over a year ago, traffic and comps have inflected at both banners with years of runway ahead. Expanded price points at the Dollar Tree banner are a potential game-changer as evidenced by Dollarama’s performance since adopting a multi-price model in 2009, offering material upside to forecast numbers.

Elite management: Years of mismanagement and underinvestment has left Dollar Tree as the #2 player in the industry behind Dollar General, but new Chairman/CEO Rick Dreiling is the ideal candidate to turn it around: he has a pristine track record of success across large/small formats in urban/rural markets including the turnaround of Dollar General (2008-2016) over which time equity value compounded 32%pa (ex. dividends).

Setup: The market is extrapolating recent issues at Dollar General to Dollar Tree, but diverging sales trajectories suggest that Dollar Tree is contributing to DG’s woes. Dollar Tree is also 1-year ahead in their investment cycle and will begin lapping SG&A step-up in Q3 just as trans-pacific freight headwinds turn to tailwinds, creating an attractive multi-year setup following recent negative revisions.

Return profile: Dollar stores have traded at an average NTM multiple of 18-20x EPS over the past 10-years (v ~16.5x today). A conservative base case yields FY26 EPS of ~$10.75 before buybacks (v consensus at ~$10) and ~$12.75 with buybacks. Applying 18x to FY26 EPS estimates yields a target price range of $190-230/share and a ~3-year IRR range of 23-30%. The bear case yields a worst case of ~$92 (~15% downside) while max NTM downside is ~20% (13x NTM EPS of $6.50).

The target price of $200/share (18.5x 2026E EPS of $10.75) offers upside of >85% (3-year IRR of ~24%), providing an attractive asymmetry without ascribing any upside related to buybacks

DOLLAR STORE INDUSTRY OVERVIEW: A GROWING, DURABLE, INSULATED SUB-SEGMENT OF RETAIL

History: the idea of a store that sold everything for $1 or less was first executed by JL Turner in 1955 when he opened the first Dollar General store in Springfield, Kentucky. By 1957, DG generated $5 million of sales across 29 stores and began attracting competition; Family Dollar was founded in 1959. The two companies went public to fuel their growth in 1968 and 1970, respectively.

Dollar Tree was founded in 1986 after Dollar General’s decision to follow Family Dollar and begin selling merchandise for >$1 in 1983. DLTR grew rapidly, listing on the NASDAQ in 1995, opening it’s 3,000th store by 2006 (DG took 47 years), and acquiring Family Dollar in 2015. Today, there are ~36k dollar stores in the US with long-term capacity currently estimated to be 50-55k stores.

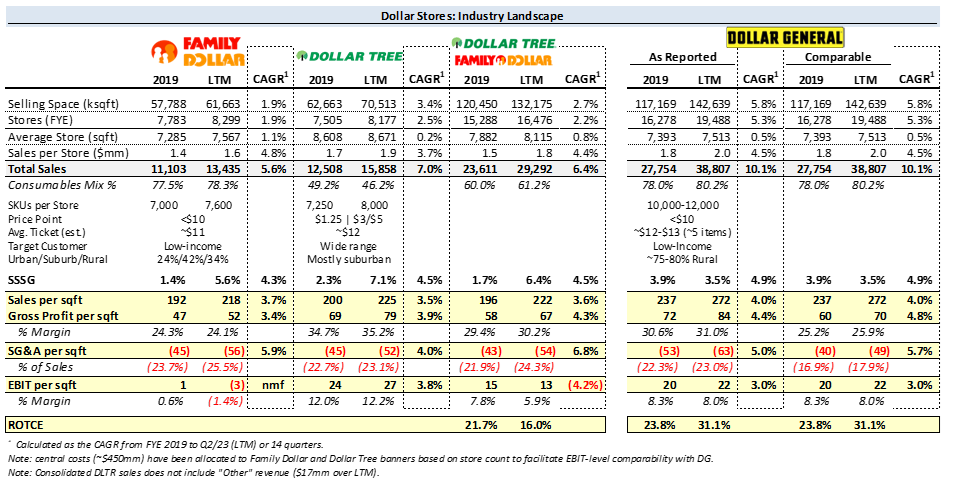

Landscape: below is an overview of DLTR and DG, which effectively control the US dollar store industry through ownership of the Family Dollar (“FD”), Dollar Tree (“DT”) and Dollar General (“DG”) banners. Note that gross profit and SG&A are not comparable due to differences in accounting policies (DLTR runs a significant portion of rent through COGS) and operating characteristics (average store size, SKU count, rural/urban skew, lease v owned DCs). Approximately comparable figures for DG are shown on the right-hand side. They key points are:

DG and FD operate similar models with high consumables mix targeting low-income households,

DT targets a wider range of consumers with its “treasure hunt” of (higher margin) discretionary items which drives the highest EBIT margins in the industry, and

Dollar General’s higher sales productivity drives material leverage on SG&A.

What do dollar stores sell? In short, dollar stores sell everything you need to get by: groceries (excluding fresh produce), personal care products (toiletries, OTC medications, cosmetics), cleaning supplies (detergents, bleach, paper towel), pet supplies, baby care, etc. The traffic driven by these consumables (typically 75-80% of sales) is a core element of the business model: maximize the number of people coming through the door with low prices on everyday essentials (typically ~25% gross margin) and expand the basket with a compelling selection of higher margin (~50%) discretionary merchandise (seasonal items, toys, electronics, apparel).

Why do consumers shop at dollar stores? As Former DG CEO David Purdue put it, dollar stores win by offering “7-Eleven convenience at Walmart prices”. A 2018 Inmar study backed this up with respondents shopping at dollar stores due to price/value (72%), convenience (53%) and the treasure hunt (36%). Top target categories were household products (64%), home décor & party goods (55%) and food (47%). The same study found that 88% of all Americans shop at dollar stores at least once annually.

Price/value: On a per-unit basis, dollar store prices are often marginally higher than Walmart’s. Dollar stores provide value to consumers by allowing them to “stretch” their dollar and complete their shopping lists at the lowest possible cost. For example, Walmart sells 92oz of Tide for $12.97 (14.1c/oz) whereas Dollar Tree offers 8oz for $1.25 (15.6c/oz). It is common for dollar store customers to visit Walmart at the beginning of the month and address needs that arise over the course of the month with “fill-in trips” (industry parlance) to dollar stores. For some households, cash is so tight that dollar stores’ small pack sizes are the only viable option. Grocery and convenience store alternatives typically offer the same SKUs at price premia of ~20% and ~40%, respectively.

Convenience: the only substitutes for the value/scope of dollar stores are the big box retailers Walmart and Target which dollar stores collectively outnumber 7:1 and 18:1, respectively. The ubiquity of dollar stores ensures a shorter drive from home or work for nearly all customers. This accessibility is augmented by the relative ease of getting in and out: parking is closer to the door, planograms minimize search costs by providing a consistent layout/experience across locations, the box is smaller and easier to navigate, the basket is smaller and the checkout lines are shorter.

These factors combine to save gas money and time, both of which low-income households are often short on. In contrast, Walmart requires customers to navigate the entire 150ksqft store by putting essentials like milk and eggs as far as possible from the entrance.

The “treasure hunt”: dollar stores (particularly the DT banner) cater not only to consumers’ love of a great deal, but also the thrill of finding one. Consumers go crazy when a social media influencer drops a limited-edition “collab” and certain dollar store items are similar in concept.

To illustrate, if you search #dollar on Instagram the #2 hashtag (behind #dollar) is #dollartree with >1mm posts followed by #dollartreefinds with 594k posts. Similarly, on TikTok, videos including the #dollartreefinds hashtag have amassed 2.4 billion views demonstrating that the value proposition is alive and well across multiple demographics. To deliver the treasure hunt, dollar stores offer a large variety of products that change often throughout the year (typically anchored by seasonal events/holidays) which create “FOMO”, compelling customers to snatch an item before its gone.

The dollar stores’ value proposition has proven resilient in the face of the “retail apocalypse”. In recent years, dollar stores have accounted for more than 50% of retail unit expansion. According to retail sales data, dollar stores have increased their share of “general merchandise” sales from 6.3% to 7.3% since 2016 (3.1% to 3.6% including food & beverage). These share gains have come largely at the expense of pharmacies, convenience stores and the long tail of independent retailers.

But how do they do it? The exhibit below provides some insight; Dollar General is used as the reference dollar store banner because its GAAP accounting is more comparable to Walmart and Target.

Real estate: the crux of the dollar store model is its real estate strategy - small, simple, consistent, no-frills boxes averaging just 8k square feet which enable:

Low overhead: rent is typically <$400/day and the store can be operated by as few as 2 people at a time or $280-420/day at $10-15/hr for total overhead as little as $800/day, and

Low start-up costs: ~$400k/store including working capital.

This combination generates attractive returns at revenue levels far lower than other concepts/formats, allowing dollar stores to operate in towns/neighborhoods that aren’t viable for other national retailers, thereby becoming the essential (sometimes the only) retailer in the area.

For example, Dollar General’s store in Faith, South Dakota serves a population of just 367 whereas the smallest town with a Walmart has 6,300 residents (Rawlins, Wyoming) and benefits from adjacent interstate traffic. The real estate strategy manifests in the financials through (1) more attractive returns/margins despite sales productivity >50% below big box, (2) lower SG&A per square foot and per store (although SG&A/sales is higher due to lower sales per square foot to leverage across fixed overhead).

Merchandising: the real estate strategy is augmented by the merchandising strategy; dollar stores offer goods in virtually all the same categories as Walmart, but stock far fewer SKUs in each category (10k total v 140k for Walmart) typically offering 1-2 national brands supplemented by private label offerings.

This concentration of SKUs reduces staffing (less time organizing/stocking) and storage needs while providing negotiating leverage with vendors who know they can be dropped from the shelves and value access to one of the fastest-growing sub-segments in retail (similar to Costco). This negotiating leverage is used to induce vendors to produce smaller pack sizes that can be sold for $1 and extract the lowest-possible price on SKUs offered by Walmart.

The merchandising strategy manifests in the financials through:

Lower sales productivity – completing the same shopping list for a fraction of the price means smaller baskets and, in rural markets, traffic per square foot is often lower as well,

Higher gross margin – by not stocking perishables, concentrating SKUs, and selling goods at (slightly) higher per unit prices dollar stores can earn higher gross margins,

Inventory per square foot – a combination of concentrating SKUs and storing most of the goods on shelves (versus designated storage areas) drives lower inventory per square foot (despite lower inventory turnover).

Note: merchandising discretionary items to facilitate the “treasure hunt” is explored in more detail in Appendix A.

No-frills: Dollar stores employ a no-frills philosophy across the business to operate profitable while offering the lowest prices. This is most evident in advertising (70bps of sales for WMT v 35bps for DLTR), store appearance (shoddier lighting, fixtures and equipment) and layout (narrower aisles with higher, tightly packed shelves) which manifests in lower SG&A/sqft.

What’s the moat? The enablers of the value proposition above are durable and growing in magnitude. The growing ubiquity of dollar stores (from ~36k today to 50-55k) will drive incremental convenience for more customers (shorter drives) and fuel further negotiating leverage with suppliers as the channel’s importance grows over time which increases the already formidable barriers to entry for would-be brick and mortar competitors.

In fact, “99 Cents Only Stores” was founded in 1982 and, despite being acquired by Ares and CPPIB in 2012, has shrunk its footprint in recent years (and has not been sold as one would expect a profitable investment of that vintage to be).

What about Walmart and other discounters? In 2013/2014 Walmart tried to break into the small box market with “Walmart Express” (15ksqft) after announcing a big push into fill-in trips, citing convenience as a key factor for the consumer. Just 2 years later, all 102 locations were closed without explanation. It is likely that Walmart struggled with (1) brand association with variety and large assortments and (2) distribution/logistics to smaller boxes at comparable economics its larger super-centers.

Similarly, Target launched a small-format store in 2012 aimed at urban markets which can be as small as 12.8ksqft, but average 40ksqft and ~20k SKUs. While they have not yet thrown in the towel, they recently halted expansion and began to close some stores (peaking at 150 total) citing difficulties with shrink/theft. Lastly, the fact that both European discounters Aldi and Lidl have struggled to meet their goals for US expansion underscores how entrenched the dollar stores are and how difficult it is to break into the US retail market (particularly in the value segment).

What about Amazon and e-commerce? To date, the impact from e-commerce on dollar stores appears minimal; as noted, dollar stores have increased the number of units opened per year against the backdrop of the “retail apocalypse” and the comps have been consistently positive (Dollar General posted its first negative comp in 32 years in 2021 following the COVID-driven surge in 2020).

There are a few key reasons:

Many low-income consumers don’t have credit cards – per the Federal Reserve’s “Report on the Economic Well-Being of US Households” in 2020, 22% of US adults were either unbanked (no bank account) or underbanked,

Low-income consumers often live in neighborhoods where there is a high likelihood that a package delivered to a doorstep would not be there when the resident returned home,

Small pack sizes and baskets drive poor shipping economics, making them less attractive to Amazon,

Many of the goods purchased at dollar stores are purchased on an as-needed basis for immediate consumption,

To find discretionary items of comparable price, one would often have to buy through Amazon’s Marketplace where

(a) quality is variable and cannot be physically inspected,

(b) the vendor still has to make money while paying Amazon a >20% take-rate, meaning it is unlikely to be of comparable quality/value, and

(c) there is no treasure hunt – choice is virtually infinite and inventory is deep – it wouldn’t make sense for a vendor to list a product in the ~$1-5 price range if they didn’t have substantial inventory to move.

In September 2022, Temu was launched in the US and has recently stoked fears that it can penetrate the wallets of dollar store customers – due to the reasons above, it is unlikely to be a long-term threat. Temu is discussed in more detail under the “risks” section in Part 2 of this report.

Other Attractive Characteristics of Dollar Stores

Recession-proof sales: the chart below illustrates the counter-cyclical nature of dollar stores dating back to 1994; sales tend to outperform during periods of economic duress (shaded in grey), but don’t underperform to the same extent during periods of economic growth. In fact, dollar stores typically acquire new customers via trade-down during difficult times and retain those customers (albeit with a lower share of wallet) as the economy recovers. This stability generates highly visible cash flows which provide greater debt capacity and enables aggressive store expansion in any economic environment.

Store growth runway: with many historically successful retail concepts struggling to grow store count, dollar stores stand out; management of both DG and DLTR have independently estimated that, at current economics, the US has capacity for 50-55k stores compared to ~36k today. In 2022, 1,230 units were added implying 12-16 years of runway at current opening rates. If new store openings accelerate to aspirational targets of ~2k/year, there remains 8-10 years of runway.

But is 50-55k really the end of the road? While this depends to some extent on the success of initiatives to improve sales productivity, there are market trends that support higher long-term store count. One of those trends that is gaining momentum and plays into the hands of the low cost, small box model is food deserts.

Food deserts: what are they and how could they expand the TAM for dollar stores?

Food deserts are tracts in which at least 100 households are located >1/2 mile from the nearest supermarket and have no vehicle access OR at least 500 people live >20 miles from the nearest supermarket (regardless of vehicle availability).

As of 2022, the USDA estimated that 17.1 million Americans live in food deserts (and growing). The growth of food deserts is being driven by the demise of local supermarkets in conjunction with national grocers pulling out of urban and rural neighbourhoods due to insufficient demand (for produce, in particular) to cover their overhead costs (the smallest box operated by Kroger is 12ksqft) and logistical difficulties (maneuvering large trailers is difficult in urban areas).

In response to backlash following the closure of 100 stores in designated food deserts, Kroger responded: “because we operate a penny profit business, we must sometimes make tough decisions in order to keep prices low for all customers”. In other words, we can’t/won’t figure out how to modify our assortment and our box is too big.

The vacuum left by grocers has created an opening for the dollar stores to leverage their smaller box and selection of shelf-stable and frozen/refrigerated foods at low prices, which further expands the runway for dollar stores. Frozen foods, in particular, are increasing in popularity nationwide (98% of Americans buy frozen food at least once per year) with US sales up 7%pa since 2019 to $70bn in 2022 or ~10% of the grocery market (+5% y/y, sustaining COVID-driven growth). The popularity of frozen foods is driven by (1) cost/waste – 80% of consumers buy frozen food to reduce waste and save money, (2) convenience – simple instructions, no prep time, quicker time to meal. This value proposition is consistent with that of dollar stores and provides an attractive growth opportunity.

The maps below demonstrate that considerable white space remains for Dollar Tree to expand into America’s food deserts.

In conclusion, dollar stores operate in a growing, durable sub-segment of retail that is insulated from e-commerce and has years of runway ahead.

DOLLAR TREE HAS AMPLE RUNWAY TO IMPROVE SALES PRODUCTIVITY AND MARGINS VIA SELF-HELP

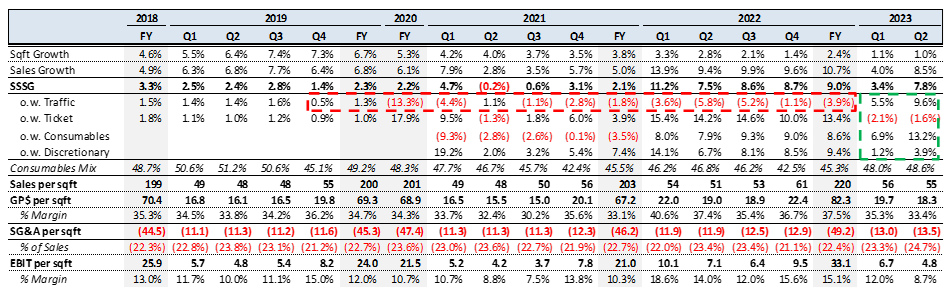

In contrast to industry bellwether Dollar General, Dollar Tree can pull multiple idiosyncratic levers to drive sales growth and margin expansion. The table below provides some context to help understand why. The key points are:

Since acquiring Family Dollar in 2015, the banner’s traffic declined consistently and profitability has followed,

Multiple failed attempts to address FD issues have distracted DLTR management, leading to traffic declines and lower SSSG at the “crown jewel” DT banner, and

Consequently, DLTR’s shares have compounded at just ~5% since 2014 following a ~34%pa increase from 2009-2014.

How did Dollar Tree get here? Key developments:

Family Dollar acquisition: Following KKR’s 2009 IPO of Dollar General, the magnitude of the turnaround underway became clear which highlighted Family Dollar’s relative underperformance. Activists began circling immediately; Trian and Bill Ackman amassed large stakes and pushed for a sale to Dollar General in 2010 and 2011, respectively, and Carl Ichan did the same in 2014. In July 2014, Dollar Tree made a surprise bid of $74.50/share. In August, Dollar General came to the table with an offer of $78.50. Shortly thereafter, Family Dollar rejected DG’s bid based on anti-trust. Ultimately, Dollar Tree acquired Family Dollar on July 6, 2015.

The stated rationale was to: (1) increase scale/buying power, (2) leverage complementary merchandising expertise (DLTR in discretionary, FDO in consumables), (3) extend reach to lower-income consumers, (4) diversify the footprint and business model (<$10 + everything for $1), (5) $300mm of cost synergies. It soon became clear that management overestimated their ability to manage and integrate a different model; Family Dollar became a distraction and performance at both banners began to suffer.

Underinvestment & mismanagement: At Family Dollar in particular, (1) gross margin-driven decision making and band-aid solutions led to uncompetitive prices and an assortment that was often mis-aligned with core customer needs and (2) underinvestment in store operations (maintenance, wages), renovations, distribution infrastructure and technology have led to erosion of customer experience (high turnover, dirty stores, shrink, poor in-stock positions, etc.). Family Dollar’s struggles led to similar (though less severe) underinvestment at Dollar Tree.

Management changes: Following the unpopular FDO transaction, CEO Bob Sasser was replaced by COO Gary Philbin (but remained Chairman). In July 20202, DLTR replaced Gary Philbin with then-COO Mike Witynski. Notably, Sasser, Philbin and Witynski were all long-time DLTR veterans and failed to acknowledge and act upon issues stemming from legacy decisions (and Bob Sasser remained chairman, looking over the shoulder of management, until 2022).

Inflation: When Dollar Tree was founded in 1986, $1 (DT sole price point until recently) was equivalent to ~$2.80 in today’s terms, dramatically reducing the scope of merchandise for buyers to offer customers. Despite a compelling case study north of the border at Dollarama and growing insistence of shareholders (Starboard launched a proxy battle in 2019 centered on the potential of DT moving to a multi-price model), former management did not view a transition of price points as necessary or inevitable.

(More) execution issues: In May 2021, Dollar Tree announced Q1 earnings and revealed that freight headwinds on trans-pacific shipping would wipe out expected earnings growth for the year, sending the shares down 8%. Q2 earnings in August were no better; DLTR reported incremental freight headwinds and its first negative comp (ex. COVID) since 2005 sending the shares down 12% to $93/share. In November, due to surging inflation and pressure from shareholders to abandon the $1 price point, management finally acquiesced and announced plans to raise the price point to $1.25 in 2022.

More activism: Amidst the inflation induced panic, Mantle Ridge filed a 13D in November 2021 revealing a 9.8% interest in Dollar Tree (at $105/share) and subsequently detailed plans to overhaul the Board and install Rick Dreiling as Chairman. By February, Dollar Tree announced that Chairman Bob Sasser would retire and in March a reconstituted Board led by Rick Dreiling was unveiled including Paul Hilal (Mantle Ridge), 5 other new directors and 5 legacy directors. Dreiling quickly began upgrading the C-suite which culminated with Dreiling assuming the CEO role for the first time since DG with the termination of CEO Mike Witynski in January of this year. Shares quickly rose to ~$140+.

“I know at Dollar General, we were very nervous that if Family Dollar and Dollar Tree got together that they'd be really good at some things. They really haven't gotten that far yet. It's been 12 years or something. It's about time. I think that Rick will force that and drive it because I'm sure he understands the synergies there”

- Former EVP at Dollar General (October 2023, Stream Transcript)

Since assuming control of the Board in Q1/22 and eventually taking over as Chairman/CEO, Rick Dreiling and his executive team got to work on extracting the full potential of both the DT and FD banners. In addition to banner-specific initiatives, several projects have been initiated for the benefit of both banners. The top 3 are:

Store operations (SG&A): In Q2/22, after just one quarter in control, management stepped up SG&A investment across both banners to invest in wages and repair & maintenance to improve store appearance and operations (cleanliness, in-stock positions, etc.). These investments were further accelerated in Q1/23 following strong initial results and are expected to moderate in 2024+. Wage investments of ~$2/hr across 2022-2023 have led to reduced turnover across the board (plotted below since higher wages came into effect), which is a key leading indicator of SSSG, shrink, in-stock positions and store cleanliness.

Renovations (Capex): to address years of underinvestment and traffic declines due in part to outdated equipment, fixtures and what new management described as décor “right out of 1975”, management have stepped-up renovations across both banners. At FD stores, ~$134k/store investment has driven 19% sales uplift and 8% traffic uplift, delivering a ~2-year payback. At DT, where underinvestment was less pronounced, $69k/store has yielded a 10% sales uplift and payback in <6 months.

Supply chain: underinvestment in supply chain infrastructure (which was never consolidated following the FD acquisition) led to poor/inconsistent DC service levels (both inbound and outbound) and a strenuous/inefficient delivery process.

To minimize labor costs at DCs, merchandise was loaded onto trucks in whatever order it came off the conveyor belt (with no organization by category). When the deliveries arrived at the store, each box was unloaded one at a time and left in the storeroom (still not organized), which led to inefficiencies when employees were searching for products resulting in poor in-stock positions. Once found, boxes were loaded onto “U-boat” carts and often left in the aisle, leading to poor store appearance. The laborious one-box-at-a-time offloading process was time consuming and limited the number of deliveries a truck could make in a given day. Finally, delivery times were erratic which made it difficult for store managers to ensure appropriate staffing, which further elongated unloading time.

To address these issues, management is investing in labor and infrastructure at the DCs to pre-sort pallets at the DC by aisle to simplify stocking/storage and implementing “rotacart” systems to shorten offload times and reduce strain on employees by enabling seamless loading/unloading of multiple boxes at once. The exhibit below provides a visual representation of the before and after. All-in, this is expected to save 5 hours per week which will be redeployed into store operations (stocking, cleaning, ensuring clear aisles, etc.) while shorter delivery times will improve fleet utilization and reduce distribution costs.

A former Senior Director of Store Operations at Dollar General validated the time/cost savings:

“I would say that KKR’s acquisition of DG and their leadership helped DG make the investments that were needed to be able to turn the corner and position itself for growth longer term… a great example was the introduction of rolltainers for delivery. All of the DG merchandise is received on rolltainers, they’re giant wheeled cages that are able to be rolled off the truck in a matter of 1-2 hours versus FD’s trucks which are dead loaded. They’re stacked carton by carton into the trailer and take 6-8 hours at least, if not longer, to unload a truck. There’s labor savings that compounded over time.”

In addition to these (and other) chain-wide initiatives, each banner has significant opportunities to drive sales productivity, which Dreiling has emphasized as the north star:

“You heard me say many times that retail is all about growing units, growing transactions and growing sales per square foot. When these retail fundamentals move in the right direction, everything else follows”.

The most consequential is DT’s move to a multi-price architecture.

Dollar Tree: The Multi-Price Opportunity

Note: for more context on the Dollar Tree banner and how it differs from FD and DG, please see Appendix A. The key points are higher discretionary mix and consequent targeting of low- and middle-income consumers with stores that are predominantly suburban which results in 40-42% of merchandise being directly imported (compared to 15-17% at FD and 9% at DG).

Why is the multi-price transition important?

Consumables drive traffic. The constraints of the $1 price point led to gradual deterioration of the consumable assortment and traffic over the past 5 years (see below) and revamping/expanding the assortment will re-ignite traffic growth.

Expanded price points strengthen the value proposition: by expanding the SKUs and categories available, customers can complete (more of) their shopping list at Dollar Tree (value/convenience) while more price points expand the aperture for buyers to provide more compelling discretionary items (treasure hunt), both of which expand the basket.

Higher traffic and price points combine to drive higher returns (sales productivity, EBIT/store) on new store investments which expands the number of viable locations at a given return threshold, thereby elongating the new store runway.

Context: following Canadian dollar store chain Dollarama’s (Bain Capital led) transition from a fixed-price “everything is $1” model to a multi-price model in 2009, calls for DT to follow suit grew louder. Management was resistant to change due to the simplicity and negotiating leverage afforded by the fixed-price model (see Appendix A) as well as fear over how consumers might respond.

By 2019, the vulnerability of the fixed price model became clear as annual price hikes by FMCGs led to a gradual deterioration of the consumables assortment which began to pressure traffic (just 60bps of y/y growth in Q4/19 – see above) and tariffs on Chinese imports began to squeeze margins on discretionary items. By 2021, it was clear change was needed; y/y traffic continued to decline despite the ~13% lower base driven by COVID and the banner printed its first negative comp (ex. COVID) in almost 15 years. This was exacerbated when trans-pacific freight rates increased by an order of magnitude (~$2k/TEU to ~$20k/TEU).

In response, former management panicked and announced they would institute a blanket price increase to $1.25 beginning in Q4/21 in addition to the gradual rollout of $3-$5 items at select stores. While they planned to upgrade ~2k consumable products to justify higher prices, most of those weren’t in stores until H2/22 meaning that consumers were paying 25% more for what was often the same product. As expected, this precipitated further traffic declines and threatened DT’s reputation for value.

Enter Rick Dreiling: joining in Q1/22, Dreiling was appalled that a value retailer would increase prices without offering incremental value in return and immediately began taking actions to restore trust with consumers: the rollout of upgraded consumable SKUs was accelerated, upgraded SKUs were expanded into more categories (notably frozen food), some SKUs were rolled back to $1 and more price points are being trialed (all <$5). These initiatives were implemented in late Q4. At the end of FY 2022, $3-$5 merchandise was rolled out to ~40% of stores.

Initial results (see below) – while it is still early, there is growing evidence that customers have accepted the multi-price model and trust has been restored:

Traffic has accelerated significantly in Q1 and continued in Q2 both y/y and q/q.

Consumables comp sales are accelerating despite lapping the price increase, demonstrating that the upgraded assortment is resonating with consumers. Dollar Tree has been growing unit volume and, more importantly, unit share steadily since the beginning of the year.

Discretionary comps remain positive after lapping the price increase despite a market-wide mix-shift towards consumables driven by inflation and a softening economy, demonstrating that the assortment remains compelling and that consumables-driven traffic continues to convert to discretionary purchases.

At the CMD in June, management revealed that DT had added 3.3 million customers over the LTM. Above all, this evidence suggests that the fervent loyalty of Dollar Tree customers stems from the value they find at Dollar Tree, not merely the $1 price point.

A closer look – why DT is positioned to benefit from enhancing the consumer value proposition vis-à-vis improved selection and category expansion (enabled by multi-price): As discussed, adding price points allows for improved value/assortment within existing categories while opening new categories that were unviable <$1 or $1.25.

Dollar Tree’s Chief Merchandising Officer Rick McNeely explains:

“Many of the new categories that are opened up, at $1.25, did not work. At $3, $4 and $5, the world is our oyster. We have the right to win here and our customers are buying it, they're just not buying from us”.

DT derives ~25% of its sales from ~4% of its customers and 75% from the top 25%. Top customers spend >90% of their wallet at competitors at an average price per unit of $4 (with 90% of items >$3) after leaving the store. Crucially, DT’s reputation for value with core customers has afforded it the benefit of being the first port-of-call for many customers. Multi-price enables customers to complete more of their list at DT, thereby enhancing convenience, positioning DT to gain significant share of wallet.

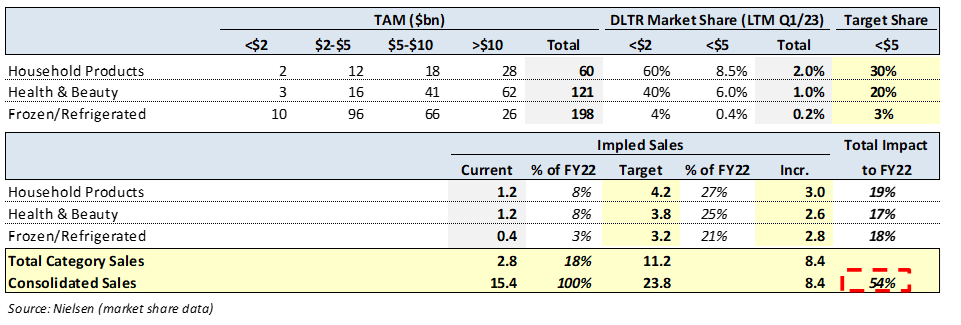

A closer look – early results in target consumable categories: to maximize sales productivity and follow through on the promise of multi-price, management has zeroed in on 3 traffic-driving categories: household products, health & beauty and frozen/refrigerated food.

Below is a slide from CMD detailing frozen/refrigerated food comps since the introduction of $3-$5 items (through Q1/23). The performance is notable given that (1) only ~40% of stores had $3-$5 SKUs and (2) within those stores, $3-$5 items were only stocked behind 3/10 cooler doors. In addition to increased traffic and impressive category comps, the average basket for a transaction including at least 1 $3-$5 cooler item is $27 compared to the chain-wide average of $12. In response to demand, management is expanding the number of doors with multi-price options from 3 to 8 chain-wide by FYE 2026.

Illustrative financial impact of success in target categories: In frozen/refrigerated food alone, expansion across the entire store base (from ~40%) and within stores (from 3 doors to 8) will drive total category sales up ~7x, notwithstanding continued comp and store growth.

To illustrate the potential tailwind to sales, the table below applies target market shares to each category based on a haircut to share in the <$2 market (to reflect greater competition); for example, if share increases from 8.5% to 30% in the <$5 household products market (v60% share in the <$2 market), household products revenue would increase by $3.0bn to $4.2bn and increase total sales by 19% off the FY22 base. The cumulative impact of these 3 categories alone at target shares below is 54% of 2022 revenue. If target shares are reached over 5/10 years, the tailwind to comps would be 9%/4%, respectively.

Note: these target market shares are for illustrative purposes and were not established by management.

Benefits to discretionary: Multi-price also benefits the sales productivity of footage allocated to discretionary merchandise by expanding the aperture of viable goods, resulting in more compelling/relevant assortments in each season (in addition to more traffic/customers to convert).

For example, when meeting management in 2019 they explained that the $1 price point limited their ability to offer the then-popular “fidget spinners” at the peak of their popularity, leading to foregone sales despite identification of the opportunity and ability to source at leading prices. This upside will be observed most clearly in seasonal assortments; YTD in 2023, discretionary comps in stores with $3-$5 items have materially outperformed those without during Easter (+12% v +2%) and Valentine’s Day (+10% v +4%) with similar outperform expected during Halloween, Thanksgiving and Christmas (which fall disproportionately in Q4). As with consumables, steady/continued expansion of $3-$5 merchandise across the store base and growing penetration of those items within stores will drive a multi-year tailwind to comps.

The blue sky scenario: The multi-year tailwind potential related to expanding multi-price penetration across and within stores can be seen through an examination of Dollarama in Canada, where the transition to multi-price has driven a decade+ tailwind to comps and remarkable improvements in box economics summarized in the table below (see Appendix B for a detailed case study).

While the Canadian retail landscape is fundamentally less competitive and margin improvements are unlikely to be of the same magnitude, continued momentum will almost certainly drive long-term operating margins above management’s FY26 target of ~15%. Importantly, as noted at the beginning of this section, improved box economics improve new store IRRs and expand the number of viable locations at a given return threshold, thereby expanding the long-term store runway.

The Dollar Tree banner’s transition to a multi-price model is management’s top priority given the banner’s strong positioning and potential for outsized LT economics. That said, Family Dollar is contributing very little to operating profit today and can move the needle for DLTR by improving EBIT margins to management’s FY26 target of ~5% (versus 8% at DG) from just 20bps over the LTM.

~End of Part 1~

We continue our discussion in Part 2, where we delve deeper into DLTR’s management, valuation, risk factors, and tactical considerations when thinking about the stock.

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe and share!

APPENDIX A: OVERVIEW OF DOLLAR TREE’S EVOLUTION

APPENDIX B: DOLLARAMA CASE STUDY

Stream by AlphaSense is an expert transcript library that helps investment analysts maximize returns with access to tens of thousands of high-quality, searchable, proprietary expert transcripts covering multiple perspectives, industries, and markets. Unlike costly and time-consuming traditional expert network calls, Stream drives faster time to insight, improves ROI, and ensures critical information isn’t missed in the research process. You can sign up for a free trial by clicking here.

Thank you, it's well written and very interesting.

The ROI of renovations is impressive, even if I don't know if it's sustainable over time.

Well articulated. excellent writeup, thx for sharing.

You mentioned, Faith South Dakota (population of 367), where a DG store is located.

I have been looking for a Dollar store that serves real rural area (like <1k population), as I couldn't get the math working. if you are familiar with that specific store in Faith, I would like to hear your insights on how that store works, esp from unit economics PoV.

thanks,

Siyu Li