Deep Dive: Alcoa (AA)

Attractive industry demand & supply, sound balance sheet, cash flows, and improving returns to shareholders

Welcome back! If you are new, subscribe below to receive monthly deep-dive research on global stock ideas and other original investment content!

Which versatile metal is positioned to enjoy strong secular demand over the coming decade from vehicle electrification, renewables, and other de-carbonization use cases? We think investors should become familiar with aluminum.

This report will explain our thesis on Alcoa - the largest North American aluminum producer - with a focus on understanding the aluminum industry fundamentals and supply & demand dynamics. Commodities have regained the spotlight since the start of the year, as investors scrambled to understand whether we are in a world headed towards a structurally higher pricing environment. If you are looking for ways to gain exposure to commodities in your portfolio, perhaps this may be a good place to start.

We think aluminum has attractive medium to long-term fundamentals, and believe the recent pull-back in prices is a good opportunity to accumulate on weakness. Aluminum is positioned as the metal of the future, benefitting from broad-based demand growth driven by de-carbonization trends. Demand is just one side of the equation however, as commodities investing cannot produce good returns without orderly supply to support prices. We take a close look at the major aluminum producing markets and examine the structural constraints to global supply. Building on top of the industry discussion, we highlight the case for an investment in Alcoa by examining the company’s assets, operations, optionalities, and valuation.

Table of contents

Aluminum Industry fundamentals

Industry 101 to get you up to speed in 10 minutes

Production process, industry structure, energy use & emissions, aluminum pricing

Global demand and supply

Long-term demand growth drivers - examining usage across industries including EV and de-carbonization demand

China’s significantly lower supply trajectory expected in the coming decade (a marked departure from the past)

Structural constraints in other markets (Europe, Russia) - will not resolve in the near-term

US aluminum industry

Overview of the current state - industry players, domestic production vs. imports, policy

Decline of the US aluminum industry, its strategic role and opportunities in re-shoring

Alcoa

Global smelting portfolio, including the economic significance of renewables power source conversion

Recent operational highlights - capacity curtailments, restarts, expansions

Optionalities, including ELYSIS joint venture

Alcoa’s investment cases summarized

Valuation

Alcoa’s P&L forecast at different LME prices

Calculating the enterprise value

Scenario-based approach

Historical and peer multiples

Aluminum industry fundamentals

First, we cover some basics of aluminum production, supply chain, industry structure, and pricing that are prerequisites for understanding the business.

Extraction, refining, and smelting

Bauxite, a reddish brown rock mined just meters above the surface of Earth, is the main source of aluminum containing about 15-25% aluminum content. 90% of global supply of Bauxite comes from tropical/subtropical regions, most notably Australia, Guinea, Vietnam, Brazil, and India. There are 29 billion tons of known bauxite reserves on Earth, and at the current rate of extraction the reserves can last more than 100 years. But there are also reports of vast undiscovered reserves that may extend it to 250-340 years and beyond. As an element, aluminum is abundant.

Bauxite is fairly widely distributed across the globe, and because it also sits close to the surface, extracting it is also relatively straightforward. The bottleneck with aluminum is not in the extraction, but in the production (refining and smelting). Production involves two main steps: alumina refining, which converts bauxite ore into aluminum oxide (called “alumina”), and aluminum smelting, which converts alumina to pure aluminum. Four tons of bauxite is refined into two tons of alumina, which is then smelted into one ton of aluminum. To give you a sense of the value-add during each production stage, the prices (Alcoa’s third-party realized prices in 2Q) were $3,864 for a ton of aluminum, $442 for a ton of alumina, and $46 for a ton of Bauxite.

Bauxite is refined into alumina with what is known as the Bayer Process. Bauxite is crushed, grounded, then mixed with heated solution of caustic soda, creating a hot slurry. It is then filtered and dried to produce Alumina in the white powdered form (illustrated below).

Aluminum is then created by running huge amounts of electricity through alumina solution in a smelter. For the scientists out there, alumina (aluminum oxide or Al₂O₃) is just aluminum atom bonded to oxygen. To get aluminum in its pure form, oxygen needs to be separated by electrolysis, and that’s where the need for electricity comes in. The energy requirement during this step is enormous, typically running at about 30-40% of total production cost. It is this massive energy requirement that is the industry bottleneck. The most important thing for Aluminum smelters is being located in a region with powerful and stable, yet low cost, and preferably renewable source of energy. This is important, and will come up again and again in this report.

Primary vs. secondary aluminum

We have so far described the process for producing “new” aluminum from bauxite ore. This is referred to as primary aluminum production. The other type is secondary aluminum, which is aluminum produced using recycled scraps. Secondary production uses a different method and only consumes 5% of energy required in primary production. Thus, it is very clean.

However, the key constraint in the secondary production is availability of scraps, since aluminum content is locked in products until they are recycled. Even with better scrap collection rates, there is an upper limit on potential secondary production. There is also a limitation to quality and purity with secondary aluminum. During the recycling process, impurities like paint, dirt, and grease are mixed in and must be treated with separation technology. This is not perfect. Most downstream makers require a mixture of primary and secondary aluminum in their products, and a certain minimum amount of primary aluminum usually has to be used in order to meet the desired properties of the alloy.

The share of secondary aluminum has remained roughly consistent at about 30-40% of primary production. There are efforts to boost secondary production including better recycling technologies, and the share of secondary aluminum is likely to increase in the future given its reduced energy consumption. But the world cannot simply run on just recycled aluminum, and will continue to increase primary production to meet the growth in future demand. The International Aluminum Institute (IAI) estimates up to 90 mmt (million metric tons) of primary aluminum will be needed by year 2050 (compared to 67 mmt of primary production in 2021). In this report, we focus on Alcoa, which is predominantly a primary producer, but also has a nascent recycled aluminum business.

Upstream vs. downstream

In primary aluminum production, upstream includes processes from bauxite mining down to aluminum smelting, while downstream includes the subsequent metal fabrication stages (shaping aluminum into semi-finished and finished forms for industries such as automotive, aerospace, packaging, and others). The industry follows a cone shape, from the concentrated upstream operations, down to the tens of thousands of downstream companies. Some of the large global players operates in both upstream and downstream (Alcoa used to be in both, but in 2016 the company split into the current Alcoa Corp, which focuses on upstream operations only, and separate company Arconic, which is a downstream player). Major US-based downstream players include Novelis, Kaiser Aluminum, Constellium, and Arconic.

The chart below shows the top ten upstream producers by production. Many of these large players, including Alcoa, are vertically integrated in their operations, which means they mine their own bauxite and refine their own alumina. Smaller aluminum producers will typically operate their own aluminum smelters but procure the inputs (bauxite and/or alumina) from the larger players.

Alcoa mines ~90% of its bauxite in Australia and Brazil, and also does alumina refining in these countries. Then, alumina needs to be shipped to where the smelters are located. Alcoa has smelters in Canada, Iceland, Norway, The United States, Spain, Brazil, Australia, and Saudi Arabia. Close to 50% of Alcoa’s non-curtailed (or active) production capacity resides in Canada (Quebec), from where Alcoa supplies to the US market.

93% of bauxite extracted by Alcoa from the mines is used internally by the company, while 7% is sold to third party. For alumina, Alcoa uses 29% internally, while selling 71% to third party. Finally, 100% of aluminum is sold to third party (to downstream players). Revenue and profit contribution (from third party sales) is split roughly between 70% aluminum and 30% alumina, although this fluctuates depending on relative pricing between the two.

Energy use and emissions

Roughly 60% of the world’s electricity consumed in aluminum smelting is self-generated by the producers. The share of self-generation is particularly high in China (about 75%), where most producers would operate their own “captive” coal powered plants. The ratio of self-generation is about 50% in the Americas. In Europe, Africa, and Oceania, virtually all of the electricity is purchased.

China relies on coal for 80-90% of energy used in aluminum production. On the other hand, hydro accounts for about 75% of production in Americas and Europe. As a result, there is a big gap in the emissions of Chinese and Western aluminum, as shown below. The flat part of the bottom curve represents Chinese producers, which emits between 16 to 17 tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum produced, compared to most Western producers at below 5 (Alcoa averages about 4).

Aluminum pricing

The London Metal Exchange (LME) is the largest exchange venue for aluminum outside of China. Keep in mind that 90% of aluminum with physical delivery are sold under bilateral contracts between producers and buyers, and not transacted on an exchange. However, the pricing in these bilateral contracts are benchmarked to LME prices. The realized price is based on the LME price, adjusted for regional premium (e.g. Midwest premium for United States) and product premium (e.g. particular shape and/or alloy, carbon-free aluminum). Alcoa’s realized prices have historically been 10-20% above LME prices reflecting these factors. Premiums can fluctuate depending on variables such as geopolitics (risks of disruption), inventory, shipping costs, tariffs, and other considerations.

Global demand & supply

We want to begin by showing two charts as a starting point to visualize the demand & supply picture.

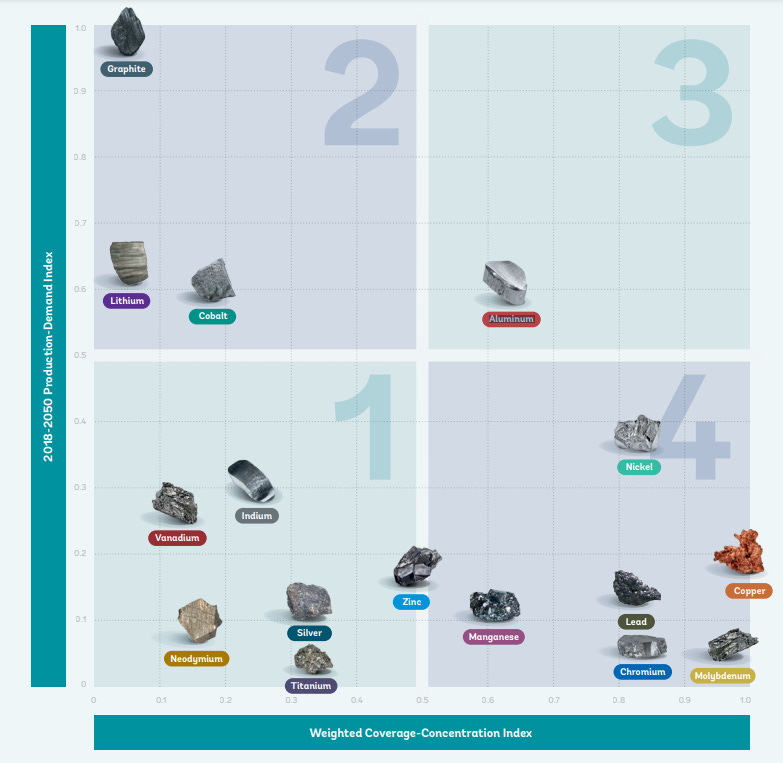

The first chart (below) illustrates how aluminum is positioned relative to other elements. It shows aluminum as the only element in the “third quadrant” on the chart. What does this mean? The x-axis measures how broadly the element is used across different types of products (technological concentration) - e.g. copper on the right being the broadest, while Lithium on the left being heavily concentrated on just a single application (i.e. batteries). The y-axis captures the degree to which the production must scale up from 2018 levels to meet estimated demand from clean energy use cases by 2050. Aluminum being in the third quadrant means that it is both broadly used AND has the biggest demand gap - illustrating the strong case for aluminum.

The chart below shows, on the right side, the estimated demand breakdown by industries by 2030. The left side breaks down the supply growth that would be required to meet this forecast.

Now, let’s dive deeper.

Demand

Consensus among most industry watchers today is that anywhere from 3-5% is a reasonable forecast for long-term annual demand growth for aluminum.

Simply put, aluminum is a highly desirable material. Key properties of aluminum that makes it such a desirable metal includes the fact that aluminum is malleable, durable, resistant to corrosion, and yet lightweight. In many industries, aluminum is positioned as the metal of the future. In certain end use cases aluminum is the desirable high-performing alternative over traditional materials such as steel, plastic, and concrete.

“Aluminum is really the material of choice in a lot of areas, also in building and construction. Don’t forget that. That’s still a very large market which is also growing. It’s transportation, building, and construction packaging that will continue to drive demand for aluminum, and especially now where the low-carbon aluminum which is produced from hydropower is a differentiated metal. There are a lot of positive indicators that aluminum is going to stay high up there for quite some time.”

- Norsk Hydro Managing Director (Stream transcript)

Nowhere else is this strong demand trend more visible than the automotive industry. Transportation is estimated to account for 32% of total aluminum demand in 2030, and out of this, about 70% comes from autos. For automakers, aluminum is a higher-performing metal than steel. It has a higher strength-to-weight ratio and is able to absorb a large amount of crash energy. This allows automakers to reduce vehicle weight without compromising on safety. Although higher performing, aluminum was passed for cheaper and heavier steel in the past. However, aluminum has been gaining increasing use in recent years as automakers focus on weight reduction to increase vehicle ranges (particularly important for EVs) and to reduce emissions.

For example, since 2015, Ford’s popular F-150 trucks have been made using full aluminum body, allowing for weight savings of 318kg compared to steel, and improvement to fuel economy of 5-29%. For EVs, weight reduction is especially important as it helps to increase battery range. Tesla’s Model S uses roughly 200 kg of aluminum (out of a total curb weight of about 2,000kg). It’s estimated that EVs have 25-35% more aluminum content per vehicle than ICE vehicles. Aluminum is becoming the metal of choice for many different auto parts – including traditional parts such as body, chassis, and structural components, but also parts that are new and unique to EVs such as the aluminum battery housing unit. Aluminum is also a component in EV charging stations.

But aluminum demand is much more than just transportation. The second largest source of demand is in construction. Aluminum is only half to 2/3rd the weight of steel structures and 1/7th the weight of reinforced concrete, but with the same bearing capacity. Aluminum is used in everything from framework to window support to HVAC and rooftop. A rule of thumb is that the more sophisticated and modern the architecture, the higher the aluminum usage tends to be. For example, the glass faces of most modern office skyscrapers are supported by lightweight aluminum frames.

Aluminum is also a key material in renewables and power storage/transmission. Aluminum is heavily used in solar (photovoltaic) panels, mostly for the frames (see below), but also inside the cells. In wind, aluminum is used for tower platform components and turbines.

In limited but growing use cases, Aluminum is positioned as a lower-cost alternative to copper. Copper has the best technical characteristics of electrical conductivity, but is facing an impending global shortage, due to increasing cost of extraction, slower rate of new mine discoveries, and extremely long mine development lead times (10-20 years). There have been successful efforts to replace copper with aluminum alloys thanks to improvements in wiring technology that compensates aluminum’s lower electrical conductivity at the same time making it less susceptible to breakage. With this, aluminum has been substituting copper in power grid cables, auto wiring, and HVAC.

For example, Saudi Electricity Co. has reportedly saved 2.4 billion riyals ($640.09 million) by shifting from copper to aluminum in its medium voltage distribution network. Japan's Kansai Electric Power also began replacing 50-year-old copper distribution cabling in Osaka with aluminum, and its plans to replace some 140,000 km of copper cabling over 30 years would save tens of billions of yen.

The more extreme the copper shortage becomes and the higher the copper price, the more the world will increasingly look to aluminum as a substitute.

“Too many forecasts ignore the fact that aluminum is a serious competitor to copper in a number of high volume applications, including high- and mid-voltage power cable, busbars, transformer windings and motor windings…In fact, given its lower cost, aluminum wins out against copper under virtually any realistic long-term price scenario” - Julian Kettle, Wood Mackenzie Senior Vice President

In consumer goods and electronics, aluminum is also highly desired. For example, the whole range of MacBook uses aluminum body. With aluminum, the notebook has a sleeker and more polished appearance. It can be made thinner and more durable than with plastic (Apple is a big advocate for the use of carbon-free aluminum in its products, and in fact it has invested in a clean aluminum JV alongside Alcoa as we’ll discuss later).

One of the most important and visible demand trends is that customers are increasingly demanding low-carbon aluminum to reduce the carbon footprint of their product lines. This is happening across all industries (shown below). For example, Norsk Hydro estimates that the proportion of low-carbon aluminum demanded by the auto industry will be 45% in 2030, and this will increase to 100% by 2050.

“We’re seeing more and more large global consumer companies specifying the use of low-carbon aluminum. We’re seeing it in the automotive business a lot. More and more in the packaging industry, also. In that regard, I think Alcoa is well-positioned to benefit from that kind of demand”

- Director, Business Development & Strategy at Alcoa (Stream Transcript)

Western aluminum makers are advantaged due to their clean production. It also means that Chinese aluminum makers cannot survive at their current state and will be forced to de-carbonize if they want to evolve with customer demands. Of course, the Chinese are not sitting still. They have embarked on a long-term mission to de-carbonize, which is the most important supply trend reshaping the aluminum industry. We explore this next.

Supply

A discussion of supply has to start with China, which possesses 55-60% of global smelting capacity. China really started to ramp up its aluminum production since around the year 2000. With massive state subsidies directed at the industry (preferential financing, tax exemptions, access to cheap electricity and land), China was singlehandedly responsible for 80-90% of total global aluminum capacity increases since 2000. The scale of state support was so massive that it created a condition whereby other countries had to follow suit with policies of their own, without which it became impossible to compete. India, Middle East, and Russia all followed suit with their own state backing for the aluminum sectors. The US aluminum industry became the biggest loser (we discuss US in more detail later).

Technically, China doesn’t actually export much of its primary aluminum production. Its downstream industry “consumes” all primary aluminum produced, and then exports semi-finished goods, such as rods, cables, and sheets. One of the reasons for this is China’s export duty of 15% imposed on unwrought primary metal. China doesn’t want its industries to just export raw material. It wants to make sure as much of the manufacturing steps (value-add) stays within the country before they are exported. Producers also enjoy a VAT rebate by exporting value-added products. Out of the roughly 39 mmt of primary aluminum that China produces each year and transforms within the country, around a third is exported.

Until around 2017, the global consensus was still that China would continue to flood the market with “unlimited” amounts of cheap and dirty aluminum. Back then, the world was still skeptical that China would commit to its promise of decarbonizing its industry. But this opinion quickly turned in the last few years, as China has demonstrated its resolute stance in tackling environmental problems, placing strict self-imposed restrictions on supply growth and directing the transition of smelting power source from coal to renewables. China surprised the industry by becoming a net importer of primary aluminum in July 2020 for the first time since 2009, and the shortage of domestic production lasted until early 2022 when China flipped back to becoming a net exporter.

At the national level, China has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and peak carbon emissions by 2030. However so far, it seems to be behind on schedule. The 14th Five-Year Plan targets 18% and 13.5% reduction in carbon intensity and energy consumption per unit of GDP respectively by 2025. In 2021, 14 out of China’s 17 aluminum-producing provinces (representing 65% of China’s aluminum production) missed at least one target and are behind on schedule. As a result, aluminum producing provinces including Inner Mongolia, Shandong, and Gansu have restricted new production capacity and have cancelled preferential smelter power tariffs.

The chart below helps visualize why the global supply dynamics of the next 10 years will look fundamentally different from the last 10 years.

The Chinese government has been instructing producers to shut down their outdated captive coal power plants and transition to low-carbon grid power. In some cases, this involves entire relocation of capacity to Southwest China, where there are abundant hydropower sources. From 2020 to 2025, 2-3 mmt of capacity will be transferred annually, with the Southwestern province of Yunnan seeing the most capacity inflows. However, not everything has gone smoothly. In late 2021, low water reservoir caused shortage in renewables energy supply which led to disruptions to smelter productions in the region, exacerbating shortages in the country. The transition to renewables has just started, and the onerous power requirements of the smelting industry will be putting the reliability of China’s renewables industry to the test.

Since the start of 2022, in a more pragmatic turn, China has relaxed some of its environmental policies. With a boost in coal production and recovery of the renewables crunch, Chinese production once again grew faster than expected. However, we believe this is just a temporary measure to address the pressing domestic shortage situation in midst of Covid shock, and does not mean that China is walking back on its long-term environmental targets. China has a self-imposed supply hard cap at 45 mmt per annum (current capacity at 39-40 mmt) which we believe it will honor. With about 2-3 mmt estimated to be illegal smelting capacity (build without authorization from government), the actual room for capacity growth is perhaps even less at only 2-3 mmt more before China bumps up against its hard cap.

China’s goal to de-carbonize its aluminum industry will be a multi-decade (at least 30-40 years) process. During this time, they will be scrapping and rebuilding their entire smelting industry – half of the world’s capacity. It’s a feat that’s quite hard to imagine in terms of the sheer scale. This transition, along with China’s self-imposed supply hard cap, could result in a constrained supply environment that could possibly last decades.

“If China keeps the new rate of expansion and slows it down a little bit compared to what we’ve seen in the last 10-15 years, I think we will see a much more balanced market in terms of supply and demand. I think the prices should probably stay in a range where the smelters are making better profits than they mostly did in the last 10-15 years”

- Director, Business Development & Strategy at Alcoa (Stream Transcript)

Now, let’s shift our focus to the rest of the world. In Europe, since the start of the year we have seen major disruptions to smelter operations and economics as a result of the higher energy costs. European natural gas has been the worst hit due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Spot natural gas prices have seen 200-500% increases. When energy accounts for 30-40% of production costs, you can imagine what this does to the profits of smelters that are exposed to spot prices. As a result, we have seen a slew of production curtailments across Europe. Year to date, Montenegro, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain have curtailed half a million ton of annual capacity.

Even if there is a near-term resolution to the Ukraine war, Europe’s energy transition is a long-term problem which will continue to create much uncertainty for energy supply in the region. Securing competitive long-term energy supply will continue to pose a challenge for European smelters, hampering their expansion plans. This could take many years, if not decades, to resolve.

Russian producer Rusal (the largest producer outside of China with 6% of global production share) has also faced disruptions. Western sanctions have not targeted Russian aluminum, which means Rusal continues ship aluminum to Western buyers. However, Australia has banned shipments of bauxite/alumina to Russia, and Rusal’s alumina refinery in Ukraine has halted operations due to the war. These have led to around 40% loss of alumina supply for Rusal. As a remedy, Rusal has been importing more alumina from China. How much Rusal can recoup remains to be seen, but noting that China has historically been a net importer of alumina, it’s uncertain if China has sufficient surplus itself to help cover Rusal’s shortfall. Rusal also faces the lack of access to Western equipment and uncertainty over future contracts with Western customers, which will further hamper its own investment plans.

China, Europe, and Russia accounts for about 70% of total global production, and these regions now face structural constraints to their supply which will likely persist for years if not decades. It’s important to recognize when an industry’s supply picture has fundamentally been altered.

The US aluminum industry

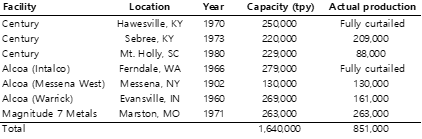

United States used to be the world’s leading aluminum producer, with 30% of global primary aluminum production share in the 1980’s across more than 30 smelters in the country. Production of primary aluminum fell from 4.6 mmt per annum in 1980, down to less than one mmt. Now, the US has just 2.4% global share of production capacity and 1.3% share of actual production.

The dire situation with US aluminum production is shown below. Only seven smelting facilities remain in the US, operated by three companies – Alcoa, Century Aluminum (46% owned by Glencore), and Magnitude 7 Metals (bought by ARG International of Switzerland during its 2016 bankruptcy). The newest US smelter opened more than forty years ago and uses older, less efficient technology. Of the seven facilities, only two are in full production today (of the remaining five, two are fully curtailed, and three are partially curtailed). The US smelting industry is running at only half the capacity due to uncompetitive costs. Over the years Alcoa and Century have moved their capacity abroad (Canada and Iceland) to take advantage of cheaper renewable energy sources.

“One of the challenges is the fact that they have aging assets. I think on the U.S. side, the assets have been pretty much let go because it was very difficult to justify a positive business case with such old assets. Also the fact that the power contracts on the U.S. side are short-term and much more expensive and less predictable.”

- Director, Business Development & Strategy at Alcoa (Stream Transcript)

The US imports about four million tons of primary aluminum per year (five times more than it produces). It gets more than two-thirds of this from Canada. Canada is the fifth largest producer of aluminum globally, with 84% of its supply exported to the US. Alcoa and Rio Tinto operates nine out of ten aluminum smelting facilities in Canada (side note: Canada’s own aluminum giant Alcan was sold to Rio Tinto in 2007). The Eastern French-speaking province of Quebec is the aluminum production capital of Canada, home to nine smelting facilities, while British Columbia on the West Coast is home to one. Canada is one of the most competitive aluminum producers in the world, benefitting from the vast amounts of cheap and renewable energy (97% generated from hydroelectric) in Quebec, making Canadian aluminum among the cleanest in the world.

The US also imports from China. But as explained earlier, recall that China doesn’t export much unwrought primary aluminum directly due to export tax. China exports semi-finished products. If we include these semi-finished products (aluminum plates and sheets, rods, structures, etc.) in addition to unwrought primary metal, then the US imports of aluminum looks like the following:

In 2017, the Trump administration took issues with the hollowing out of the US aluminum industry, regarding it as not just a jobs problem but more critically, a national security problem. In 2018, the administration imposed a 10% tariff on all aluminum imports. Shortly after, this was lifted for Canada and Mexico, as pressures mounted from the partners (who put up their own retaliatory tariff on US exports), and also from US’s own downstream sector and manufacturers that protested against the cost increases. The tariffs remained in place until 2021, when Biden lifted the tariff on EU aluminum producers. Currently, because of the extraordinarily high levels of inflation, there is discussions of lifting this further for China (aluminum is likely a part of this deal although it hasn’t been stated explicitly). Biden is undoing the trade policies from the Trump era. However, much of this could change with the next election cycle.

Aluminum is one of the most critical backbones of any industry, including defense. In 2018, US Department of Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security commissioned a study outlining aluminum’s importance for national security:

“The U.S. currently has five smelters remaining, only two smelters that are operating at full capacity. Only one of these five smelters produces high-purity aluminum required for critical infrastructure and defense aerospace applications, including types of high performance armor plate and aircraft-grade aluminum products used in upgrading F-18, F-35, and C-17 aircraft. Should this one U.S. smelter close, the U.S. would be left without an adequate domestic supplier for key national security needs. The only other high-volume producers of high-purity aluminum are located in the UAE and China”

This is referring to Century’s Hawesville Smelter, which is the producer of high-purity aluminum (average purity level of 99.9% versus standard of 99.7%) used for defense and aerospace applications. On June 22, Century announced that it will halt production at Hawesville for 9-12 months, citing rising energy costs. Hawesville happens to be the only one of its kind not just in the United States, but in the Western Hemisphere and among NATO allies. If this doesn’t sound an alarm for US politicians, then what will?

Alcoa, a former giant

Nobody talks about Alcoa anymore, but in its heyday the company was truly one of America’s industrialization icons. Alcoa was founded in 1888 by a young chemist named Charles Martin Hall, who is considered the founding father of modern aluminum production. Aluminum cookware was one of the first mass use cases of aluminum, and it became so successful that Alcoa founded its own cookware subsidiary. In the early 1900’s, aluminum made its way into industrial use cases, from military equipment during the first world war to automobile and aviation/space programs. Aluminum took over industries by storm, and Alcoa was singlehandedly responsible for aluminum’s adoption in all these new markets.

The Great Depression led to the collapse of sales by more than 60% and mass layoffs for Alcoa, but the company’s dominance remained unchallenged. Eventually, the business recovered, and by 1940’s Alcoa was so dominant that the government had called for a breakup of Alcoa’s aluminum monopoly. In fact, Alcoa’s antitrust trial was the largest of US legal proceeding until that time. Eventually, Alcoa was ruled in violation of antitrust law in 1945. During the Second World War, the government had financed the construction of Alcoa’s new plants to meet the surge in wartime demand. This led to surplus capacity in the industry after the war ended. To implement the breakup of Alcoa’s monopoly, the government decided that these new plants will be sold off to new entrants in the industry - Reynolds Metal Company and Pemanente Metals. With this, the Alcoa monopoly was officially broken. In 1950, the industry capacity was split among Alcoa with 50.9% share, Reynolds with 30.9%, and Kaiser Aluminum (Permanente) with 18.2%.

From 1950’s to 1970’s, given the increased competition in the industry, Alcoa looked for new ways to grow. It established an international presence, and also expanded more into downstream. It partnered with the Japanese manufacturer Furukawa Electric to form Furalco, which supplied aluminum aircraft parts for Lockheed. It also focused more on value-added products, which had higher margin than primary aluminum, such as aluminum-based construction products. But the biggest trend of all was that aluminum cans started to become a very popular form of beverage packing in the 1960’s, which helped drive significant growth for demand.

The 1990’s kick started another wave of growth via acquisition and consolidation. Typical of the late-cycle, Alcoa looked for every chance to acquire other companies and buy growth. Alcoa paid billions to acquire several downstream companies during this time. In 1999 it paid $4.8 billion to take over Reynolds Metal, undoing the industry breakup of the earlier era. But ever since 2000, US aluminum production would enter a steeply declining stage. China started to write a new chapter for the industry, as we have already discussed. Alcoa would spend the next 20 years dismantling its century-old aluminum empire, becoming a shadow of its former self.

Alcoa’s smelting assets

Alcoa’s production capacity is summarized above. Focusing on aluminum smelting (right side of the chart), Alcoa has about 2.96 mmt of smelting capacity globally, out of which 0.9 mmt is currently curtailed (temporary suspension of operations). Canada remains the most important production region accounting for almost 50% of Alcoa’s non-curtailed capacity.

Energy accounts for roughly 30% of Alcoa’s aluminum production costs. Energy is procured based on long-term contracts. Generally speaking, fossil fuel energy contracts are exposed to spot prices of natural gas and coal. With renewables, which have no marginal cost of production, most contracts are fully or partially linked to aluminum (LME) prices. This means with renewables, energy cost can adjust in lockstep with Alcoa’s topline, providing more stable smelting margins. As long as a sufficient and stable supply of renewables power can be procured (this is the challenging part), it allows smelters to make a profit on a wider range of aluminum prices.

Today, 81% of Alcoa’s smelting portfolio is powered by renewables, and 65% of energy cost is LME-linked. For the 19% of smelting portfolio that is not powered by renewables, encouragingly Alcoa has either announced plans or made progress to convert a substantial portion of it into renewables in the future:

All of Alcoa’s smelters in Canada, Norway, Iceland, and New York Messena currently runs on renewables

In late 2021 Alcoa curtailed San Ciprian (Spain) for two years due to soaring natural gas costs. San Ciprian is now being converted to renewables, and Alcoa has signed a 10-year renewables (wind) deal with a renewables developer. This deal which will supply San Ciprian with enough power to restart operations in 2024 at 45% capacity. Alcoa is also pursuing renewables options for the remaining 55%.

Alumar (Brazil) is in the process of being converted to 100% renewables by 2024.

Portland (Australia) currently runs on coal. Alcoa announced in 2021 that it is collaborating with an energy firm (wind) to eventually convert into 100% renewables.

Intalco (US) previously ran on renewables, but has been curtailed due to the inability to secure a renewables supply contract due to shortages in the region.

The only facility that is not currently powered by renewables and in which Alcoa has not announced any plans for conversion is Warrick, which runs on captive coal power.

Alcoa also has a 25.1% stake in a JV with Saudi Arabian Mining Company (Ma’aden) in Ras Al Khair (accounted for in “other income”). This is a highly competitive asset, considered the largest and most efficient integrated aluminum manufacturing facility in the world (bauxite, alumina, and smelting all in one complex). Alcoa’s pro-rata share of capacity is roughly 0.2 mmt.

Recent operating highlights

Over the past decade, Alcoa has been focused on “rightsizing” its production capacity due to challenging market conditions. It has also been selling non-core assets, including legacy land and downstream assets. 2015/16 was a particularly challenging time for aluminum prices, and during this time Alcoa curtailed Alumar (0.27 mmt) and Warrick (0.27 mmt). In the spring of 2020, due to the dramatic decline in global aluminum demand and uncertainty that was created by Covid, Alcoa curtailed Intalco, its biggest facility in the US (0.28 mmt).

Things changed dramatically in 2021 with worsening supply chain and shortages across the entire commodities space. Aluminum prices went from the Covid lows of ~$1500/t in March 2020 to $3000-4000/t two years later. Alcoa is now trying to restart its curtailed capacity in Portland (Australia) and Alumar (Brazil). The company has also announced in June it will increase Mosjoen (Norway) by 14k tons per year by end of 2026 (7% capacity expansion), and a production increase at Deschambault smelter in Quebec. Alcoa is focused on selectively growing capacity via restarts and capacity “creeps” at existing facilities, while driving shift towards renewables energy supply in the medium to long term for the majority of its portfolio.

Alcoa’s US facilities have been a pain the neck for management. Intalco, having been curtailed at the start of Covid in 2020, has been at a deadlock in trying to secure a new renewables supply contract. Smelters are massive users of energy, which ends up competing with local residential use and other commercial uses (e.g. datacenters of tech giants in the Pacific Northwest which are also heavy users of energy), resulting in power shortages in the region. This is enough of a challenge for Alcoa that it has been exploring the sales of Intalco. Earlier this year Alcoa signed a LOI with Blue Wolf, a private equity firm, which has expressed an interest to purchase the facility.

“It’s always been a question mark for me. When you have an aluminum company that wants to get rid of one of those assets, then there are hedge funds or investment companies who sometimes take it over and run it for a couple of years. I never don’t quite understand it, personally. How does that work? If an aluminum company cannot get it to work, how does somebody else is able to make money with it?”

- Norsk Hydro Managing Director (Stream transcript)

On July 1st, Alcoa announced further curtailment at Warrick. Warrick has already been operating at 60% utilization before this, and further curtailment of one of three operating lines will reduce utilization down to 40%. This follows the permanent closure of Wenatchee smelter (State of Washington) in December 2021. The US aluminum industry seems to be headed into further decline.

Yet, we think there exists medium to long-term optionality of being one of the only two major US aluminum producer remaining. For example, potential import restrictions and increase in tariffs on aluminum from America’s adversaries in the future could play out favorably for US-based producers leading to higher regional premiums. The extent to which Alcoa will benefit from future trade/industrial policy will depend on future US election outcomes, but there is option value here that may not be fully appreciated yet. Alcoa will be a beneficiary from further geopolitical and supply chain decoupling.

“In these conditions, suppliers like Alcoa that produce in markets with structural deficits like North America and Europe remain in an advantaged position as many consumers prefer domestic suppliers with integrated supply chain. Those consumers have also looked to move away from relying on riskier imported volumes”

– Alcoa CEO Roy Harvey, Q2 2022 earnings call

The biggest risk in the near term is a demand pullback. But despite all the fears circulating, this doesn’t seem to be happening yet:

“Realistically, what we’re seeing right now is that demand continues to grow for the year. And so we continue to have a good full order book. We have constant conversations with our customers…we continue to see very strong premiums, very strong order books and value-added. And so while there is great uncertainty, I think, it continues to be a good story on demand.”

– Alcoa CEO Roy Harvey, Q2 2022 earnings call

Inventory level at LME warehouses have been declining throughout July, indicating continued tightness (inventory builds tends to happen fast in the case of real demand crises).

ELYSIS joint venture

Alcoa has a 48% stake in a joint venture with Rio Tinto called ELYSIS, which is developing a new technology known as inert anode. The technology eliminates all direct greenhouse gases from the traditional smelting process (electrolysis), producing only oxygen as a byproduct. Alcoa calls this a breakthrough technology that “has the potential to transform the aluminum industry”. Interestingly, Apple has invested $13 million in the JV, in addition to becoming an earlier adopter/buyer for the aluminum produced using this technology. Audi has also signed on as a buyer.

According to CEO Roy Harvey, the current timeline is to “have a proven technology by the end of 2024” followed by a design phase for commercialization and deployment, with the first commercial production scheduled in 2026. As shown below, this is a significant part of Alcoa’s plans to get to zero emissions by 2050.

Alcoa’s investment case summarized

Industry backdrop of secular demand growth and structurally constrained global supply bodes well for aluminum prices to be well supported.

Vertically integrated upstream operations ensures supply stability and provides insulation from volatility in alumina and bauxite prices.

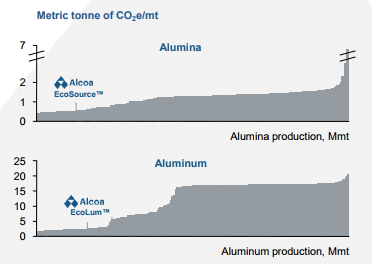

World-class alumina refining assets in the first quartile of global cost curve, and smelting assets in the second quartile (likely also first quartile if excluding US and some of the curtailed capacities).

Large share of smelters powered by renewables (65% of energy cost linked to LME prices) which allows majority of energy costs to adjust down during downcycles, protecting margins. Plans for further renewables conversion for a substantial part of the portfolio in the medium to long-term.

Producer in markets with structural deficits (US and Europe) and well-positioned to enjoy strong regional and value-added premiums. Beneficiary of further supply chain/geopolitical de-coupling.

Leadership in low-carbon products including optionality of ELYSIS

Optionality to benefit from future favorable industrial/trade policies as one of the two remaining major US aluminum producers.

Valuation

The average aluminum prices over the last 10 and 20 years have been $1,948 and $2,010 respectively (LME unalloyed primary ingots, high grade, minimum 99.7% purity). For all the reasons discussed in this report, we believe that the supply & demand bodes well for stronger aluminum prices over the medium to long term. We look at valuation with LME price of $2,000 being our bear case, $2,500 as the base case, and $3,000 as the bull case ($2,389 as of the time of this writing - August 4, 2022).

Alcoa has been able to maintain positive EBIT generation in the last five years, even during periods of unprecedented Covid demand decline of 2020 (Note: we wish we could go back further in history but financials starts at 2017 due to split of the company into Alcoa and Arconic in 2016).

Below we estimate the annual EBIT generation in each of the pricing scenarios (aluminum pricing at $2,000/$2,500/$3,000). Note the calculations here are based on annualized second quarter 2022 shipment volumes, and does not include future smelter restart optionality for curtailed capacity. If we assume the full restarts of Portland, Alumar, and 45% restart of San Ciprian by 2024 as per management guidance, this could add another 0.371 mmt of annualized production (additional 18% of non-curtailed capacity), contributing to additional profit growth. Therefore this should be a conservative estimate.

Alcoa’s enterprise value is calculated below. Balance sheet is in the best position it has ever been thanks to previous years’ deleveraging efforts and improved cash flows.

Stock is trading at the low range of its historical LTM EV/EBIT (range: 3.4 - 24x)

On a free cash flow basis, Alcoa generated $383 of free cash flow (net of distributions to non-controlling interest) in Q2, in a price environment of $2,879 average LME price during the quarter. On an annualized basis, Alcoa’s equity trades at 5.3x free cash flow.

Alcoa trades at roughly median peer valuation (2.8x LTM EV/EBITDA vs. 2.2-5.1x peer group range)

Notably, Alcoa started paying a small dividend since Q4 2021 (quarterly dividend of $0.10 per share). The company returned $406.5 million to investors since Q4 through dividends ($56.5m) and stock repurchase ($350m). In July, management announced an additional $500 million authorized for future stock repurchases. These are signals of management’s increasing confidence in the business.

“We have confidence in the strength of the company and so we provided returns to shareholders in the second quarter as our cash balance was strong, our cash generation was strong, and we have confidence in the future ability of the company to weather through cyclical storms”

– Alcoa CFO Bill Oplinger, Q2 2022 earnings call

On July 26th, credit rating agency Moody’s upgraded Alcoa’s rating to Baa3 (from Ba1), citing the following:

“The ratings upgrade to Baa3 reflects the improved competitiveness of Alcoa's refining and smelting system that will support its ability to generate strong earnings and positive free cash flow and help it sustain an investment grade credit profile at various aluminum, alumina and bauxite prices. Moody's views Alcoa's substantially strengthened balance sheet, excellent liquidity position and its financial policy as supportive of the investment grade rating"

We agree, and believe the Alcoa story will continue to find more interest among investors.

Disclosure: The author has positions in the securities mentioned in this article.

If you are looking for an expert network to get up to speed on industries and companies, then we highly recommend Stream by Alphasense.

Stream by Alphasense is an expert interview transcript library that has been integral to our research process. Select quotes we used in this research were sourced from Stream. They are a fast growing expert network with over 15,000 transcripts on a wide variety of industries (TMT, consumers, industrials, real estate and more). We recommend Stream for its high quality transcript library (70% of experts are found exclusively on Stream) and easy-to-use interface. You can sign up for a free trial by clicking here.

Thanks for the knowledge, good stuff!

The process uses only termal coal, or is met coal also used?

To me AA has a similar story as X .... by the way, you could do a write up on steel too :)

I learned a lot from this - thanks